Miles Malleson

Miles Malleson | |

|---|---|

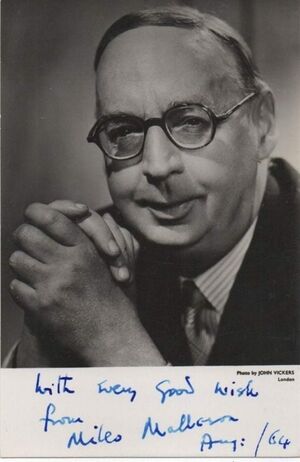

Malleson promotional head shot | |

| Born | William Miles Malleson 25 May 1888 |

| Died | 15 March 1969 (aged 80) London, England, UK |

| Other names | Miles Malieson |

| Occupation | Actor/screenwriter |

| Years active | 1921– 1965 |

| Spouse(s) | Lady Constance Malleson (1915–1923) Joan G. Billson (1923–1940) Tatiana Lieven (1946–1969) |

William Miles Malleson (25 May 1888 – 15 March 1969) was an English actor and dramatist, particularly remembered for his appearances in British comedy films of the 1930s to 1960s. Towards the end of his career he also appeared in cameo roles in several Hammer horror films, with a fairly large role in The Brides of Dracula as the hypochondriac and fee-hungry local doctor. Malleson was also a writer on many films, including some of those in which he had small parts, such as Nell Gwyn (1934) and The Thief of Bagdad (1940). He also translated and adapted several of Molière's plays (The Misanthrope, which he entitled The Slave of Truth, Tartuffe and The Imaginary Invalid).

Biography

Malleson was born in Avondale Road, South Croydon, Surrey, England, the son of Edmund Taylor Malleson (1859-1909), a manufacturing chemist, and Myrrha Bithynia Frances Borrell (1863-1931), a descendant of the numismatist Henry Perigal Borrell and the inventor Francis Maceroni. (Miles' cousin and contemporary, Lucy Malleson, had a long career as a mystery novelist, mostly under the pen name "Anthony Gilbert".)

He was educated at Brighton College and Emmanuel College. At Cambridge, he created a sensation when it was discovered that he had successfully posed as a politician and given a speech instead of the visitor who had failed to attend a debating society dinner.[1]

As an undergraduate, Malleson made his first stage appearance in November 1909, playing the slave Sosias in the biennial Cambridge Greek Play production of Aristophanes' 'The Wasps' presented at the New Theatre, Cambridge.

He turned professional in November 1911. He studied acting at Herbert Beerbohm Tree's Academy of Dramatic Art, which later was renamed the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA). Here he met his first wife in 1913.

In September 1914, he enlisted in the Army, and was sent to Malta, but was invalided home and discharged in January 1915. In late 1915, Malleson met Clifford Allen, who converted Malleson to pacifism and socialism.[2] Malleson subsequently became a member of the peace organisation, the No-Conscription Fellowship.[2] By June 1916 he was writing in support of conscientious objectors.[3] Malleson wrote two anti-war plays, "D" Company and Black 'Ell. When the plays were published in book form in 1916, copies were seized from the printers by the police, who described them as "a deliberate calumny on the British soldier".[4][5] Malleson was a supporter of the Bolshevik revolution and a founder member of the socialist 1917 Club in Soho. Another play of Malleson's, Paddly Pools, (a children's play with a socialist message) was frequently performed by British amateur dramatic groups in the period after World War I.[6]

In the 1920s, Malleson became director of the Arts Guild of the Independent Labour Party. In this capacity Malleson helped establish amateur dramatics companies across Britain. The Arts Guild also helped stage plays by George Bernard Shaw, John Galsworthy and Laurence Housman, as well as Malleson's own work.[7] His 1934 play Six Men of Dorset (written with Harvey Brooks), about the Tolpuddle Martyrs, was later performed by local theatre groups under the guidance of the Left Book Club Theatre Guild.[5][8]

Malleson married three times and had many relationships. In 1915, he married writer and aspiring actress Lady Constance Malleson, who was also interested in social reform. Theirs was an open marriage and they divorced amicably in 1923 so that he could marry Joan Billson; they divorced in 1940. His third wife was Tatiana Lieven, whom he married in 1946 and from whom he had been separated for several years at the time of his death.[9]

Malleson had a receding chin and a sharp nose that produced the effect of a double chin. His manner was gentle and absent-minded; his voice, soft and high. He is best remembered for his roles as the Sultan in The Thief of Bagdad (1940), the poetically-inclined hangman in Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), and as Dr. Chasuble in The Importance of Being Earnest (1952). He was capable of excellent classical performances. For example, in 'Sir John Gielgud A Life in Letters', edited by Richard Mangan (Arcade Publishing 2004), p. 74, Gielgud notes that Malleson was 'splendid' as Polonius in Hamlet.

Failing eyesight led to his being unable to work in his last years. He died in March 1969, following surgery to remove cataracts and was cremated in a private ceremony. A memorial service was held at w:St Martin-in-the-Fields during which Sybil Thorndike and Laurence Olivier gave readings.[10]

Partial filmography

As actor

- The Headmaster (1921) .... Palliser Grantley

- The W Plan (1930) .... Minor Role (British Version) (uncredited)

- The Yellow Mask (1930) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Night Birds (1930) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Children of Chance (1930) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- City of Song (1931) .... Theatre Watchman

- The Woman Between (1931) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Sally in Our Alley (1931) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Night in Montmartre (1931) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- The Blue Danube (1932) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Frail Women (1932) .... The Registrar

- The Water Gipsies (1932) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- The Sign of Four (1932) .... Thaddeus Sholto

- The Mayor's Nest (1932) .... Clerk

- Love on Wheels (1932) .... Academy of Music Porter

- Thark (1932)

- The Love Contract (1932) .... Peters

- Money Means Nothing (1932) .... Doorman

- Strange Evidence (1933) .... (uncredited)

- Perfect Understanding (1933) .... Announcer

- Bitter Sweet (1933) .... The Butler

- Summer Lightning (1933) .... Beach

- The Queen's Affair (1934) .... The Chancellor

- Evergreen (1934) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Nell Gwynn (1934) .... Chiffinch

- Falling in Love (1934) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Brewster's Millions (1935) .... Hamilton Higginbottom Button (uncredited)

- Lazybones (1935) .... Pessimist

- The 39 Steps (1935) .... Palladium Manager (uncredited)

- Vintage Wine (1935) .... Henri Popinot

- Peg of Old Drury (1935) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Rhodes of Africa (1936) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Tudor Rose (1936) .... Jane's Father

- Knight Without Armour (1937) .... Drunken Red Commissar

- Victoria the Great (1937) .... Sir James the Physician

- The Rat (1937) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Action for Slander (1938) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- A Royal Divorce (1938) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Sixty Glorious Years (1938) .... Wounded Soldier (uncredited)

- Q Planes (1939) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- The Lion Has Wings (1939) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- For Freedom (1940) .... Minor Role

- The Thief of Bagdad (1940) .... Sultan

- Major Barbara (1941) .... Morrison

- This Was Paris (1942) .... Watson, Newspaper Librarian

- They Flew Alone (1942) .... Vacuum Salesman

- Unpublished Story (1942) .... Farmfield

- The First of the Few (1942) .... Vickers Representative (uncredited)

- Thunder Rock (1942) .... Chairman of Directors

- The Gentle Sex (1943) .... Guard

- The Demi-Paradise (1943) .... Theatre Cashier

- Dead of Night (1945) .... Hearse Driver/Bus Conductor

- Journey Together (1945) .... (uncredited)

- While the Sun Shines (1947) .... Horton

- The Mark of Cain (1947) .... Mr. Burden (uncredited)

- One Night with You (1948) .... Jailer

- The Idol of Paris (1948) .... Offenbach

- Bond Street (1948) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Saraband for Dead Lovers (1948) .... Lord of Misrule

- Woman Hater (1948) .... Vicar

- The History of Mr. Polly (1949) .... Old gentleman on punt

- Cardboard Cavalier (1949) .... Judge Gorebucket

- The Queen of Spades (1949) .... Tchybukin

- The Perfect Woman (1949) .... Prof. Ernest Belman

- Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949) .... The Hangman

- Adam and Evelyne (1949) .... Undetermined Supporting Role (uncredited)

- Train of Events (1949) .... Johnson, the timekeeper (segment "The Engine Driver")

- Golden Salamander (1950) .... Douvet

- Stage Fright (1950) .... Mr. Fortesque

- The Man in the White Suit (1951) .... The Tailor

- Scrooge (1951) .... Old Joe

- The Magic Box (1951) .... Orchestra Conductor

- The Woman's Angle (1952) .... A. Secrett

- The Happy Family (1952) .... Mr. Thwaites

- Treasure Hunt (1952) .... Mr. Walsh

- The Importance of Being Earnest (1952) .... Canon Chasuble

- Venetian Bird (1952) .... Grespi

- Trent's Last Case (1952) .... Burton Cupples

- Folly to Be Wise (1953) .... Dr. Hector McAdam

- The Captain's Paradise (1953) .... Lawrence St. James

- Geordie (1955) .... Lord Paunceton

- King's Rhapsody (1955) .... Jules

- Private's Progress (1956) .... Mr. Windrush Snr.

- The Man Who Never Was (1956) .... Scientist

- The Silken Affair (1956) .... Mr. Blucher

- Dry Rot (1956) .... Yokel

- Three Men in a Boat (1956 film) .... Baskcomb, 2nd Old Gentleman

- Brothers in Law (1957) .... Kendall Grimes QC

- The Admirable Crichton (1957) .... Vicar

- Campbell's Kingdom (1957) .... Minor Role (uncredited)

- Barnacle Bill (1957) .... Angler

- The Naked Truth (1957) .... Rev. Cedric Bastable

- Happy Is the Bride (1958) .... 1st Magistrate

- Gideon's Day (1958) .... The Judge

- Dracula (1958) .... Undertaker

- Behind the Mask (1958) .... Sir Oswald Pettiford

- Bachelor of Hearts (1958) .... Dr. Butson

- Kidnapped (1959) .... Mr. Rankeillor

- The Captain's Table (1959) .... Canon Swingler

- Carlton-Browne of the F.O. (1959) .... Resident Advisor Davidson

- The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959) .... Bishop

- I'm All Right Jack (1959) .... Windrush Snr.

- And the Same to You (1960) .... Bishop

- Peeping Tom (1960) .... Elderly Gentleman Customer

- The Day They Robbed the Bank of England (1960) .... Assistant Curator

- The Brides of Dracula (1960) .... Dr. Tobler

- The Hellfire Club (1961) .... Judge

- Fury at Smugglers' Bay (1961) .... Duke of Avon

- Double Bunk (1961) .... Reverend Thomas

- Postman's Knock (1962) .... Psychiatrist

- Go to Blazes (1962) .... Salesman

- The Phantom of the Opera (1962) .... 2nd Cabby

- The Brain (1962) .... Dr. Miller

- Call Me Bwana (1963) .... Psychiatrist (uncredited)

- Heavens Above! (1963) .... Rockeby

- Circus World (1964) .... Billy Hennigan

- First Men in the Moon (1964) .... Dymchurch Registrar

- Murder Ahoy! (1964) .... Bishop Faulkner

- A Jolly Bad Fellow (1964) .... Dr. Woolley

- You Must Be Joking! (1965) .... Salesman (final film role)

As screenwriter

- Night Birds (1930)

- The W Plan (1930)

- Two Worlds (1930)

- A Night in Montmartre (1931)

- Children of Fortune (1931)

- City of Song (1931)

- Sally in Our Alley (1931)

- The Water Gipsies (1932)

- Strange Evidence (1933)

- Lorna Doone (1934)

- Nell Gwyn (1934)

- Tudor Rose (1936)

- Victoria the Great (1937)

- Action for Slander (1937)

- The Thief of Bagdad (1940)

- The First of the Few (1942)

- They Flew Alone (1942)

- Squadron Leader X (1943)

- The Adventures of Tartu (1943) (uncredited)

- They Met in the Dark (1943)

- Yellow Canary (1943)

Playwright credits

- Youth A Play in Three Acts

- The Little White Thought A Fantastic Scrap

- "D" Company

- Six men of Dorset: A play in three acts (with Harvey Brooks)

- Paddly Pools: A Little Fairy Play

- The Bet: A Play in One Act (based on a short story by Chekov)

- Black 'Ell (1916); Malleson's anti-war play was refused permission for performance in 1916, and not produced in the UK until 1925

- Michael (1917) adapted from the short story What Men Live By by Leo Tolstoy

- The Artist (1919) adapted from the short story An Artist's Story by Anton Chekhov

- Conflict (1925) Revived by Mint Theater Company in June 2018 [11]

- Yours Unfaithfully (1933); Revived by Mint Theater Company in 2016. Performed off-Broadway in New York City for a limited run in early-2017 starring Max von Essen.[12]

- The Glorious Days (1952) musical play, co-wrote the book with Robert Nesbitt

- Molière: Three Plays (1960); contains The Slave of Truth (Le Misanthrope), Tartuffe and The Imaginary Invalid

Translation work

Malleson translated many plays by Molière, including Le bourgeois gentilhomme, L'avare, L'école des femmes,[13] Le Misanthrope, Tartuffe, Le malade imaginaire and the one-act play Sganarelle. He also adapted a German play, Flieger, by Hermann Rossmann, under the English title The Ace. This was later filmed as Hell in the Heavens.

He wrote the subtitles for a filmed version of a Comédie Française production of Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, which was shown at the Academy Cinema in London in 1962.[14]

Vocal work

In 1964, he, Roger Livesey, Terry-Thomas, Rita Webb, Avril Angers, and Judith Furse, recorded 'Indian Summer of an Uncle', and 'Jeeves Takes Charge' for the Caedmon Audio record label, (Caedmon Audio TC-1137-s).

References

- ^ Catherine De La Roche (1 October 1949). "Miles of Characters". w:Picturegoer magazine.

- ^ a b Arthur Marwick, Clifford Allen: the open conspirator. London, Oliver & Boyd, 1964(pg. 66-67)

- ^ Miles Malleson: Cranks and Commonsense, 1916; Miles Malleson: Second Thoughts, nd [1916]

- ^ [[w:Raphael Samuel|]], [[w:Ewan MacColl|]], [[w:Stuart Cosgrove|]], Theatres of the left, 1880-1935: Workers' Theatre Movements in Britain and AmericaLondon, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985. ISBN 9780710009012 (p.25)

- ^ a b John Lucas, The Radical Twenties: Writing, Politics, and Culture. Rutgers University Press, 1999 ISBN 9780813526829 (p. 39, 166)

- ^ Kimberley Reynolds, Left Out : the forgotten tradition of radical publishing for children in Britain 1910-1949. Oxford : [[w:Oxford University Press|]], 2016.ISBN 9780191820540 (pg. 52, 218)

- ^ Ros Merkin, "The Religion of Socialism or a pleasant Sunday afternoon?: the ILP Arts Guild", in Clive Barker and Maggie B. Gale (ed.), British Theatre Between the Wars, 1918-1939. [[w:Cambridge University Press|]], 2000 ISBN 9780521624077 (pgs. 162-189).

- ^ Andy Croft, Red Letter Days : British Fiction in the 1930s. London : Lawrence & Wishart, 1990. ISBN 9780853157298 (pg. 205)

- ^ Malleson, Andrew Discovering the Family of Miles Malleson 1888 to 1969 (2012) pg 267 [[w:Google Books|]]

- ^ Malleson, Andrew pg 268

- ^ Teachout, Terry (June 21, 2018). "'Conflict' Review: A Political Play Without Preaching". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Soloski, Alexis. "Review: 'Yours Unfaithfully,' on an Open Marriage and Its Pitfalls". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Swan Theatre Company School for Wives production".

- ^ Daily Telegraph 23 December 1982, p.8

External links

- Pages with script errors

- Pages using infobox person with multiple spouses

- Find a Grave template with ID not in Wikidata

- Alumni of Emmanuel College, Cambridge

- English male film actors

- English male screenwriters

- People from Croydon

- People educated at Brighton College

- 1888 births

- 1969 deaths

- 20th-century English male actors

- British male comedy actors

- Pranksters

- English dramatists and playwrights

- English socialists

- English pacifists

- 20th-century English screenwriters

- 20th-century English male writers