Whisky Galore! (1949 film)

| Whisky Galore! | |

|---|---|

| The faces of Basil Radford and Joan Greenwood appear in a cartoon whisky bottle; the top of the bottle wears a Tam o' shanter and tartan scarf UK film poster by Tom Eckersley | |

| Directed by | Alexander Mackendrick |

| Written by | |

| Based on | Whisky Galore by Compton Mackenzie |

| Produced by | Michael Balcon |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gerald Gibbs[1] |

| Edited by | Joseph Sterling |

| Music by | Ernest Irving |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | General Film Distributors (UK) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 82 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

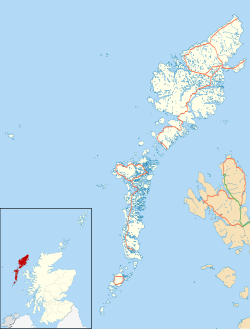

Whisky Galore! is a 1949 British comedy film produced by Ealing Studios, starring Basil Radford, Bruce Seton, Joan Greenwood and Gordon Jackson. It was the directorial debut of Alexander Mackendrick; the screenplay was by Compton Mackenzie, an adaptation of his 1947 novel Whisky Galore, and Angus MacPhail. The story—based on a true event—concerns a shipwreck off a fictional Scottish island, the inhabitants of which have run out of whisky because of wartime rationing. The islanders find out the ship is carrying 50,000 cases of whisky, some of which they salvage, against the opposition of the local Customs and Excise men.

It was filmed on the island of Barra; the weather was so poor that the production over-ran its 10-week schedule by five weeks, and the film went £20,000 over budget. Michael Balcon, the head of the studio, was unimpressed by the initial cut of the film, and one of Ealing's directors, Charles Crichton, added footage and re-edited the film before its release. Like other Ealing comedies, Whisky Galore! explores the actions of a small insular group facing and overcoming a more powerful opponent. An unspoken sense of community runs through the film, and the story reflects a time when the British Empire was weakening.

Whisky Galore! was well received on release. It came out in the same year as Passport to Pimlico and Kind Hearts and Coronets, leading to 1949 being remembered as one of the peak years of the Ealing comedies. In the US, where Whisky Galore! was renamed Tight Little Island, the film became the first from the studios to achieve box office success. It was followed by a sequel, Rockets Galore!. Whisky Galore! has since been adapted for the stage, and a remake was released in 2016.

Plot

The inhabitants of the isolated Scottish island of Todday in the Outer Hebrides are largely unaffected by wartime rationing until 1943, when the supply of whisky runs out. As a result, gloom descends on the disconsolate islanders. In the midst of this catastrophe, Sergeant Odd returns on leave from the army to court Peggy, the daughter of the local shopkeeper, Joseph Macroon. Odd had previously assisted with setting up the island's Home Guard unit. Meanwhile, Macroon's other daughter, Catriona, has just become engaged to a meek schoolteacher, George Campbell, although Campbell's stern, domineering mother refuses to give her approval.

During a night-time fog, the freighter SS Cabinet Minister runs aground near Todday in heavy fog and begins to sink. Two local inhabitants, the Biffer and Sammy MacCodrun, row out to lend assistance, and learn from its departing crew that the cargo consists of 50,000 cases of whisky. They quickly spread the news.

Captain Waggett, the stuffy English commander of the local Home Guard, orders Odd to guard the cargo, but Macroon casually remarks that, by long-standing custom, a man cannot marry without hosting a rèiteach—a Scottish betrothal ceremony—in which whisky must be served. Taking the hint, the sergeant allows himself to be overpowered, and the locals manage to offload many cases before the ship goes down. Campbell, sent to his room by his mother for a prior transgression, is persuaded to leave through the window and assist with the salvage by MacCodrun. This proves fortunate, as Campbell rescues the Biffer when he is trapped in the sinking freighter. The whisky also gives the previously teetotal Campbell the courage to stand up to his mother and insist that he will marry Catriona.

A battle of wits ensues between Waggett, who wants to confiscate the salvaged cargo, and the islanders. Waggett brings in Macroon's old Customs and Excise nemesis, Mr Farquharson, and his men to search for the whisky. Forewarned, islanders manage to hide the bottles in ingenious places, including the ammunition cases that Waggett ships off the island. When the whisky is discovered in the cases, Waggett is recalled by his superiors on the mainland to explain himself, leaving the locals triumphant.

Cast

|

|

Production

Pre-production

Whisky Galore! was produced by Michael Balcon, the head of Ealing Studios; he appointed Monja Danischewsky as the associate producer.[2] Danischewsky had been employed in the studio's advertising department, but was becoming bored by the work and was considering a position in Fleet Street;[3] Whisky Galore! was his first job in production.[2] The film was produced at the same time as Passport to Pimlico and Kind Hearts and Coronets,[4] and with the studio's directors all working on other projects, Danischewsky asked Balcon if Alexander Mackendrick, one of Ealing's production design team, could direct the work. Balcon did not want novices as producer and director, and persuaded Danischewsky to select someone else. They asked Ronald Neame to direct, but he turned the offer down and Mackendrick was given the opportunity to make his debut as a director.[5] With studio space limited by the other films being produced, Balcon insisted that the film had to be made on location.[6]

The screenplay was written by Compton Mackenzie and Angus MacPhail, based on Mackenzie's novel; Mackenzie received £500 for the rights to the book and a further £1,000 because of the film's profitability.[7] Mackendrick and Danischewsky also worked on the script before further input from the writers Elwyn Ambrose and Donald Campbell and the actor James Robertson Justice, who also appeared in the film.[8] The film and novel's story was based on an incident in the Second World War, when the cargo ship SS Politician ran aground in 1941 off the north coast of Eriskay in the Outer Hebrides. Local inhabitants from the island and from nearby South Uist heard that the ship was carrying 22,000 cases of whisky; they rescued up to 7,000 cases from the wreck before it sank. Mackenzie, a Home Guard commander on the island, took no action against the removal of the whisky or those who took it;[9][10] Charles McColl and Ivan Gledhill, the local Customs and Excise officers, undertook raids and arrested many of those who had looted whisky.[11]

The plot underwent some modification and condensation from the novel, a lot of the background being removed; in particular, much of the religious aspect of the novel was left out, the novel's Protestant Great Todday and Roman Catholic Little Todday being merged into the single island of Todday.[12] Mackenzie was annoyed with aspects of the adaptation and, referring to the removal of the religious divide, described the production as "[a]nother of my books gone west".[13]

Alastair Sim was offered the role of Joseph Macroon in the film, but turned it down to avoid being typecast as "a professional Scotsman".[14] It had been Mackenzie's ambition to appear in a film, and he was given the role of Captain Buncher, the master of SS Cabinet Minister, as Politician was renamed in the book and film.[3] Most of the cast were Scottish—with the exception of two of the lead actors, Basil Radford and Joan Greenwood—and many of the islanders from Barra were used as extras.[9]

In May 1950 the British Film Institute's monthly publication, Sight & Sound, estimated the film's budget to be around £100,000.[15][a] The following month, Balcon wrote to the magazine to complain that "Your estimate of the cost is wrong by more than a thousand or two". He also stated in his letter that the film "over-ran its budget by the unprecedented figure of 60 per cent to 70 per cent".[17] Roger Hutchinson, who wrote a history of the sinking of Politician, states that the budget was £60,000.[3]

Filming

Filming began in July 1948 on the island of Barra; a unit of 80 staff from Ealing was on location. As most of the established production staff were working on other films at Ealing, many of Mackendrick's team were inexperienced.[18][19] On what was supposed to be the first day of filming, Mackendrick threw away the script and had Mackenzie and MacPhail rewrite it over two days. For a box of cigars, Mackenzie was persuaded to add material to the script from his 1943 novel Keep the Home Guard Turning.[20] He played no part after the initial filming: according to the film historian Colin McArthur, Mackenzie had an "impatient disengagement from the filming and marketing".[21][b] The summer of 1948 brought heavy rain and gales and the shoot ran five weeks over its planned 10-week schedule and the film went £20,000 over budget.[18][c]

The church hall on the island was converted into a makeshift studio, which included basic soundproofing. Nearly everything had to be brought from the mainland for filming and many of the sets had been prefabricated in Ealing; the islanders were perplexed by some of the items the crew brought with them, such as the artificial rocks they added to the already rock-strewn landscape.[22][23] The studio also had to send out three cases of dummy whisky bottles, as the island was short of the real equivalent because of rationing.[24] The location shooting meant the use of a mobile studio unit for filming. This was one of the earliest uses by a British studio.[25]

With only one small hotel on the island, the cast were housed with the islanders, which had the advantage that it helped the actors pick up the local accent for the film. One local, who was adept at Scottish dancing, stood in as the body double for Greenwood in the rèiteach scene; Greenwood, a talented ballet dancer, could not master the steps of the reel, and the feet of one of the islanders were filmed.[26]

There was tension between Danischewsky and Mackendrick during filming, which led to disagreements; this included a difference of opinion concerning the moral tone of the film. Mackendrick sympathised with the high-minded attempts of the pompous Waggett to foil the looting, while Danischewsky's sympathy lay with the islanders and their removal of the drink.[19][27] Mackendrick later said: "I began to realise that the most Scottish character in Whisky Galore! is Waggett the Englishman. He is the only Calvinist, puritan figure – and all the other characters aren't Scots at all: they're Irish!"[10]

Mackendrick was unhappy with the film; as the cast and crew were preparing to return to London, he told Gordon Jackson that the film would "probably turn out to be a dull documentary on island life".[28] He later said "It looks like a home movie. It doesn't look like it was done by a professional at all. And it wasn't".[29]

Post-production

Balcon disliked the completed rough cut of Whisky Galore!—mostly put together from the rushes—and his initial thought was to cut its running time down to an hour and classify it as a second feature.[30] He did not provide Mackendrick with another directoral role, but assigned him to second unit work.[31] The initial editing had been done by Joseph Sterling, who was relatively inexperienced. Another of Ealing's directors, Charles Crichton, shot more footage at Ealing Studios and re-edited the film closer to the version Mackendrick had produced.[32][33] Crichton said "All I did was put the confidence back in the film".[34] The Crichton version was the one released to cinemas.[35]

Mackendrick was still not satisfied with the final film and thought it looked like an amateur work. Because of financial pressures on the studio Balcon decided to release it with little promotion.[d] John Jympson, one of the editors at Ealing, recommended the film to his father, Jympson Harman, the film critic for The Evening News. Although there was to be no trade viewing, Harman and several other press reviewers visited the studios to see the film. They all wrote good reviews, which forced Balcon to provide funds for promotion.[36]

Danischewsky later called the film "the longest unsponsored advertisement ever to reach cinema screens the world over"; the whisky producer The Distillers Company later presented those associated with the film a bottle of whisky each, given at a dinner at the Savoy Hotel in London.[37]

Music

The music for Whisky Galore! was composed by Ernest Irving, who had been involved in several other productions for Ealing Studios. His score incorporated adaptations of themes from Scottish folk music to include in his compositions,[38] and used the Scotch snap musical form to reinforce the theme.[39] The musicologist Kate Daubney writes that Irving's score "Seems positively lush with its expansive seascapes and emotive expressions of anxiety in the community".[40] The opening music to the film begins with English brass notes, but this changes to Scottish melodies; Daubney describes how the "balance of material evokes the English-Scottish relationship which will emerge in the film's story".[41]

One scene in the film, soon after the first whisky has been rescued from the ship, shows the male islanders celebrating the return of whisky to the island by drinking and singing in unison in puirt à beul (trans: "mouth music"). According to McArthur, the music and the action show a social, communal event, with whisky the central focus of their enjoyment.[42] The tune was "Brochan Lom", a nonsense song about porridge.[43] The scene mixed the professional actors and local islanders; Crichton said it was not possible to differentiate between the two in the final film.[44]

Scottish folk music is used for the accompaniment of the eightsome reel, which is danced at the rèiteach. According to the music historian Rosemary Coupe, the dance and music are "a vibrant expression of the Scottish spirit, second only to the 'water of life' itself".[45]

Themes

Whisky Galore! primarily centres on the conflict between two men, Macroon and Waggett; women have what McArthur describes as "peripheral roles".[46] Much of the film's humour is at the expense of Waggett, and the film historian Mark Duguid considers there is a "cruel bite" to it.[9] Waggett is described by the cultural historian Roger Rawlings as a fish-out-of-water on Todday;[47] he is the intruder in a film that contains what the film historian Christine Geraghty describes as "a narrative of rural resistance".[48] Not all outsiders to the island are intruders: the other Englishman, Sergeant Odd, "acts as the audience's entry point into the community",[49] and immerses himself in the island's ways.[50] Whisky Galore! is one of several films that show an outsider coming to Scotland and being "either humiliated or rejuvenated (or both)", according to David Martin-Jones, the film historian.[51][e]

Jonny Murray, the film and visual culture academic, considers the Scottish characters in the film as stereotypes: "the slightly drunk, slightly unruly local, the figures who are magically cut adrift or don't seem to respect at all the conventions of how we live in the modern world".[52] He likens the film's portrayals of the Scottish to the portrayals in the Kailyard school of literature, which represents a false image of Scotland.[52][f] The film historian Claire Mortimer sees the Western Isles as portrayed as "being a magical space which is outside of time and the 'real' world".[53] This is true of both Whisky Galore! and Mackendrick's other Scottish-based Ealing comedy, The Maggie. Both films evoke "a tension between myth and reality in the portrayal of the idyllic island community".[54]

McArthur, in his work comparing Whisky Galore! to The Maggie, identifies what he sees as "the Scottish Discursive Unconscious" running through the film: an examination of the ethnicity of "the Scots (in particular the Gaelic-Speaking, Highland Scots) as having an essential identity different from—indeed, in many respects the antithesis of—the Anglo-Saxon identified by (a certain class of) Englishmen".[55] According to McArthur, this view of the Scots has permeated much of British culture, influenced by Sir Walter Scott, Felix Mendelssohn, James Macpherson, Sir Edwin Landseer, Sir Harry Lauder and Queen Victoria.[56] The critic John Brown argues that the film, created by outsiders to the community, tries to "embody some kind of definitive essence", but fails to do so, although the result is not unsympathetic.[57]

According to Daubney, the islanders "relish their isolation and simple way of life and go to considerable lengths to protect it against a moral code imposed from outside".[58] An unspoken sense of community runs through the film, according to Geraghty, such as in salvaging the whisky, and particularly in the rèiteach scene; immediately coming from that celebration, the islanders come together to hide the whisky when they hear the customs men are on their way.[59] Martin-Jones—describing the scene as a cèilidh—considers that it offers a Kailyard image which "illustrates the curative charms Scotland offers to the tourist or visiting outsider".[60]

Mackendrick's biographer, Philip Kemp, identifies different strands of comedy, including what he describes as "crude incongruity",[61] "verbal fencing—beautifully judged by the actors no less than the director in its underplayed humour"[62] and "near-surreal" conversations.[63] Martin-Jones sees such flexibility in approach as a method to allow important points in the plot to make themselves apparent.[64]

The film historians Anthony Aldgate and Jeffrey Richards describe Whisky Galore! as a progressive comedy because it upsets the established social order to promote the well-being of a community.[65] In this, and in the rejection of the colonial power by a small community, Aldgate and Richards compare the film to Passport to Pimlico.[66] The device of pitting a small group of British against a series of changes to the status quo from an external agent leads the British Film Institute to consider Whisky Galore!, along with other of the Ealing comedies, as "conservative, but 'mildly anarchic' daydreams, fantasies".[67] Like other Ealing comedies, Whisky Galore! concerned the actions of a small insular group facing and overcoming a more powerful opponent. The film historian George Perry writes that in doing so the film examines "dogged team spirit, the idiosyncrasies of character blended and harnessed for the good of the group".[68] Like Passport to Pimlico, Whisky Galore! "portrays a small populace closing ranks around their esoteric belief system that English law cannot completely contain".[69] Along with the other Ealing comedies, this rejection of power and law reflects a time when the British Empire was weakening.[69]

Release and reception

Whisky Galore! was released into UK cinemas on 16 June 1949[70] and was financially successful.[71] In France, the film was retitled Whisky à gogo; the name was later used as that of a discothèque in Paris.[72] Whisky Galore! was released in the US in December 1949,[70] though because of restrictions on the use of the names of alcoholic drinks in titles, the film was renamed Tight Little Island.[73] The film was given an open certification in most territories, allowing people of all ages to see it, but in Denmark it was restricted to adults only. The Danish censor explained "There is in this film an obvious disregard for ordinary legislation, in this case the law against smuggling ... Also, we believed that it was damaging for children to see alcohol portrayed as an absolute necessity for normal self-expression".[70]

Critics warmly praised Whisky Galore! on its release.[74] C. A. Lejeune, writing in The Observer, considered it "a film with the French genius in the British manner";[75] the reviewer for The Manchester Guardian thought the film was "put together with ... tact and subtlety",[76] and Henry Raynor, in Sight & Sound magazine, called it "one of the best post-war British films".[77] Several critics identified the script as excellent and The Manchester Guardian's reviewer thought that the main credit for the film should be given to Mackenzie and MacPhail for the story.[76] Lejeune thought that the story was treated "with the sort of fancy that is half childlike and half agelessly wise: it accepts facts for what they are and only tilts their representation, ever so slightly, towards the fantastic and the humorous".[75]

The acting was also praised by many critics; Lejeune wrote that the actors portray "real people doing real things under real conditions",[75] and the reviewer for The Monthly Film Bulletin considered that "a talented cast sees to it that no island character study shall go unnoticed", while the lead roles "make the most of their opportunities".[78] The critic for The Manchester Guardian considered Radford to have played his part "with unusual subtlety" and thought that among the remainder of the cast "there are so many excellent performances that it would be unfair to pick out two or three names for special praise".[76] The critic Bosley Crowther, writing in The New York Times, thought that Radford and Watson were the stand-out actors of the film, although he also considered the rest of the cast strong.[79]

The film surprised many at Ealing Studios for the level of popularity it gained in the US, where it became Ealing's first to achieve box office success.[74] For Crowther, "the charm and distinction of this film reside in the wonderfully dry way it spins a deliciously wet tale".[79] T. M. P. in The New York Times wrote that the film was "another happy demonstration of that peculiar knack British movie makers have for striking a rich and universally appealing comic vein in the most unexpected and seemingly insular situations".[80]

Whisky Galore! was nominated for the British Academy Film Award for Best British Film, alongside Passport to Pimlico and Kind Hearts and Coronets, although they lost to The Third Man (1949).[81]

Legacy

Rockets Galore, Mackenzie's sequel to Whisky Galore, was adapted and filmed as Rockets Galore! in 1958, with direction from Michael Relph. Danischewsky provided the screenplay, and several of the personnel who filmed Whisky Galore! also worked on Rockets Galore! [82][83] Whisky Galore!—along with Mackendrick's other Scottish-based Ealing comedy The Maggie (1954)—had an influence over later Scottish-centred films, including Laxdale Hall (1953), Brigadoon (1954), The Wicker Man (1973), Local Hero (1983) and Trainspotting (1996).[84][85] Much of the influence is because of the Kailyard effect used in Whisky Galore!, according to the author Auslan Cramb.[52]

Whisky Galore! was produced at the same time as Passport to Pimlico and Kind Hearts and Coronets; all three comedies were released in UK cinemas over two months.[4] Brian McFarlane, writing in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, states that although it was not an aim of releasing the three films together, together they "established the brand name of 'Ealing comedy'";[86] Duguid writes that the three films "forever linked 'Ealing' and 'comedy' in the public imagination".[9] The film historians Duguid, Lee Freeman, Keith Johnston and Melanie Williams consider 1949 was one of two "pinnacle" years for Ealing, the other being 1951, when The Man in the White Suit and The Lavender Hill Mob were both released.[87]

In 2009 Whisky Galore! was adapted for the stage as a musical; under the direction of Ken Alexander, it was performed at the Pitlochry Festival Theatre.[88] In June 2016 a remake of the film was premiered at the Edinburgh International Film Festival; Eddie Izzard played Waggett and Gregor Fisher took the role of Macroon.[89] The critic Guy Lodge, writing for Variety, thought it an "innocuous, unmemorable remake" and that there was "little reason for it to exist".[90] In contrast, Kate Muir, writing in The Times thought "the gentle, subversive wit of the 1949 version has been left intact".[91]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ £100,000 in 1948 equates to approximately £5 million in 2023, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[16]

- ^ At heart, Mackenzie was an imperialist and had an opportunity to travel to India to write a history of the Indian Army.[21]

- ^ £20,000 in 1948 equates to approximately £900,000 in 2023, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[16]

- ^ Two previous films from Ealing, Saraband for Dead Lovers and Scott of the Antarctic (both 1948) had been expensive to produce and neither had a good return at the box office.[29]

- ^ Other films to show this include Laxdale Hall (1953), The Maggie (1954), Trouble in the Glen (1954), Brigadoon (1954), Rockets Galore! (1957), Local Hero (1983), Loch Ness (1996), The Rocket Post (2004) and Made of Honour (2008).[51]

- ^ Murray describes Kailyard as "images of Scotland that portrayed it as parochial, cut off from the modern world, small-town, hapless lads, winsome lassies. They certainly weren't something you could recognise yourself in".[52]

References

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 1.

- ^ a b Sellers 2015, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Hutchinson 2007, p. 135.

- ^ a b Barr 1977, p. 80.

- ^ Sellers 2015, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Distilling Whisky Galore!, 8 January 1991, Event occurs at 11:15–11:30.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 20.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d Duguid 2013.

- ^ a b Romney 2011, p. 42.

- ^ "Customs and Excise". Merseyside Maritime Museum.

- ^ McArthur 2003, pp. 16–18.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 16.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 34.

- ^ "The Front Page". Sight & Sound.

- ^ a b Clark 2018.

- ^ "Whisky Galore". Sight & Sound.

- ^ a b McArthur 2003, p. 24.

- ^ a b Sellers 2015, p. 149.

- ^ Distilling Whisky Galore!, 8 January 1991, Event occurs at 14:30–14:55.

- ^ a b McArthur 2003, p. 15.

- ^ Sellers 2015, p. 147.

- ^ Distilling Whisky Galore!, 8 January 1991, Events occur at 13:35–13:45 and 21:50–21:57.

- ^ Hutchinson 2007, p. 140.

- ^ Honri 1967, p. 1121.

- ^ Distilling Whisky Galore!, 8 January 1991, Events occur at 17:50–18:10 and 21:35–21:45.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 27.

- ^ Hutchinson 2007, p. 141.

- ^ a b Sellers 2015, p. 150.

- ^ McArthur 2003, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Sellers 2015, pp. 182–183.

- ^ McArthur 2003, pp. 24, 27–28.

- ^ Distilling Whisky Galore!, 8 January 1991, Event occurs at 41:40–41:50.

- ^ Distilling Whisky Galore!, 8 January 1991, Event occurs at 41:50–42:00.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Sellers 2015, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Sellers 2015, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Duguid et al. 2012, p. 107.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 35.

- ^ Daubney 2006, p. 62.

- ^ Daubney 2006, p. 63.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 47.

- ^ Bell 2019, p. 1966.

- ^ Distilling Whisky Galore!, 8 January 1991, Event occurs at 42:00–42:20.

- ^ Coupe 2010, p. 716.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Rawlings 2017, p. 73.

- ^ Geraghty 2002, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Geraghty 2002, p. 46.

- ^ Geraghty 2002, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Martin-Jones 2010, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b c d Cramb 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Mortimer 2015, p. 413.

- ^ Mortimer 2015, p. 411.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 8.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 12.

- ^ Brown 1983, p. 41.

- ^ Daubney 2006, p. 61.

- ^ Geraghty 2002, p. 44.

- ^ Martin-Jones 2010, p. 163.

- ^ Kemp 1991, p. 27.

- ^ Kemp 1991, p. 30.

- ^ Kemp 1991, p. 31.

- ^ Martin-Jones 2010, p. 29.

- ^ Aldgate & Richards 1999, p. 155.

- ^ Aldgate & Richards 1999, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Duguid et al. 2012, p. 137.

- ^ Perry 1981, p. 111.

- ^ a b Rawlings 2017, p. 74.

- ^ a b c McArthur 2003, p. 81.

- ^ Sellers 2015, p. 51.

- ^ Doggett 2016, p. 353.

- ^ Fidler 1949, p. 12.

- ^ a b Sellers 2015, p. 151.

- ^ a b c Lejeune 1949, p. 6.

- ^ a b c "New Films in London". The Manchester Guardian.

- ^ Raynor 1950, p. 68.

- ^ "Whisky Galore (1948)". The Monthly Film Bulletin.

- ^ a b Crowther 1950, p. 1.

- ^ T. M. P. 1949, p. 33.

- ^ "Film: British Film in 1950". British Film Institute.

- ^ McArthur 2003, p. 100.

- ^ "Rockets Galore (1958)". British Film Institute.

- ^ Romney 2011, p. 42; Cramb 2016, p. 5; Mortimer 2015, p. 413.

- ^ Duguid et al. 2012, p. 225.

- ^ McFarlane 2005.

- ^ Duguid et al. 2012, p. 9.

- ^ "Stage Design; Going off-screen". Design Week.

- ^ Macnab 2016, p. 41.

- ^ Lodge 2017.

- ^ Muir 2017.

Sources

Books

- Aldgate, Anthony; Richards, Jeffrey (1999). Best of British: Cinema and Society from 1930 to Present. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-288-3.

- Barr, Charles (1977). Ealing Studios. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7153-7420-7.

- Bell, Emily A. (2019). "Singing and Vocal Practices". In Sturman, Janet (ed.). The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. pp. 1961–1968. doi:10.4135/9781483317731.n650. ISBN 978-1-5063-5338-8. S2CID 239288360.

- Daubney, Kate (2006). "Music as a Satirical Device in the Ealing Comedies". In Mera, Miguel; Burnand, David (eds.). European Film Music. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 60–72. ISBN 978-0-7546-3659-5.

- Doggett, Peter (2016). Electric Shock: From the Gramophone to the iPhone – 125 Years of Pop Music. London: Random House. ISBN 978-0-09-957519-1.

- Duguid, Mark; Freeman, Lee; Johnston, Keith M.; Williams, Melanie (2012). Ealing Revisited. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-84457-510-7.

- Geraghty, Christine (2002). British Cinema in the Fifties: Gender, Genre and the 'New Look'. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-69464-8.

- Hutchinson, Roger (2007). Polly: The True Story Behind Whisky Galore. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-8401-8071-8.

- Kemp, Philip (1991). Lethal Innocence: The Cinema of Alexander Mackendrick. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-4136-4980-5.

- Martin-Jones, David (2010). Scotland: Global Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-8654-4.

- McArthur, Colin (2003). Whisky Galore! & The Maggie: A British Film Guide. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-633-1.

- Mortimer, Claire (2015). "Alexander Mackendrick. Dreams, Nightmares, and Myths in Ealing Comedy". In Horton, Andrew; Rapf, Joanna E. (eds.). A Companion to Film Comedy. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 409–431. ISBN 978-1-1191-6955-0.

- Perry, George (1981). Forever Ealing. London: Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-0-907516-60-6.

- Rawlings, Roger (2017). Ripping England!: Postwar British Satire from Ealing to the Goons. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-6733-7.

- Sellers, Robert (2015). The Secret Life of Ealing Studios. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-78131-397-8.

Journals and magazines

- Brown, John (Winter 1983). "The Land Beyond Brigadoon". Sight & Sound. 53 (1): 40–46.

- Coupe, Rosemary (2010). "The Evolution of the 'Eightsome Reel'". Folk Music Journal. 9 (5): 693–722. ISSN 0531-9684. JSTOR 25654208.

- "The Front Page". Sight & Sound. 19 (3): 103–104. May 1950.

- Honri, Baynham (November 1967). "Milestones in British Film Studios and Their Production Techniques – 1897–1967". Journal of the SMPTE. 76 (11): 1116–1121. doi:10.5594/J13675. ISSN 0361-4573.

- McFarlane, Brian (22 September 2005). "Ealing Studios (act. 1907–1959)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/93789. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Raynor, Henry (April 1950). "Nothing to Laugh At". Sight & Sound. 19 (2): 68.

- "Stage Design; Going off-screen". Design Week: 14. 6 August 2009.

- "Whisky Galore". Sight & Sound. 19 (4): 182. June 1950.

- "Whisky Galore (1948)". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 16 (181–192): 117.

Newspapers

- Cramb, Auslan (28 December 2016). "How Compton Mackenzie may have helped to pave the way for Trainspotting". The Daily Telegraph. p. 5.

- Crowther, Bosley (15 January 1950). "In Blythe Spirits". The New York Times. p. 1.

- Fidler, Jimmie (23 November 1949). "Jimmie Fidler in Hollywood". The Joplin Globe. p. 12.

- Lejeune, C. A. (19 June 1949). "Tipping a Winner". The Observer. p. 6.

- Macnab, Geoffrey (5 July 2016). "A Toast to Whimsy and Nostalgia". The Independent. p. 41.

- Muir, Kate (5 May 2017). "Whisky Galore!". The Times. Retrieved 16 November 2019. (subscription required)

- "New Films in London". The Manchester Guardian. 18 June 1949. p. 5.

- Romney, Jonathan (24 July 2011). "Another Shot of Scotch on the Rocks with a Splash of Wit". The Independent on Sunday. p. 42.

- T. M. P. (26 December 1949). "Based on Compton Mackenzie Novel". The New York Times. p. 33.

Websites

- Clark, Gregory (2018). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "Customs and Excise take a different view". Merseyside Maritime Museum. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- Duguid, Mark (2013). "Whisky Galore! (1949)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Film: British Film in 1950". British Film Institute. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Lodge, Guy (12 May 2017). "Film Review: 'Whisky Galore!'". Variety. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "Rockets Galore (1958)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

Other

- Cooper, Derek (8 January 1991). Distilling Whisky Galore! (Television production). Channel 4.

External links

- Whisky Galore! at AllMovie

- Whisky Galore! at the British Film Institute

- Whisky Galore! at IMDb

- Whisky Galore! at Screenonline

Template:Alexander Mackendrick Template:Michael Balcon Template:Compton Mackenzie Lua error in Module:Authority_control at line 182: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).

- Pages with script errors

- Articles with short description

- Use dmy dates from May 2016

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Use British English from May 2016

- Pages with broken file links

- Template film date with 1 release date

- Articles containing Scottish Gaelic-language text

- GSD articles incorporating a citation from the ODNB

- Pages using cite ODNB with id parameter

- Pages containing links to subscription-only content

- IMDb title ID not in Wikidata

- Featured articles

- 1949 comedy films

- 1948 in Scotland

- 1949 films

- Barra

- British black-and-white films

- British comedy films

- Ealing Studios films

- English-language Scottish films

- Films based on British novels

- Films set in the Outer Hebrides

- Films set on the home front during World War II

- Films shot in Scotland

- Films set on beaches

- Films about alcoholic drinks

- Films directed by Alexander Mackendrick

- Films produced by Michael Balcon

- 1949 directorial debut films

- 1940s English-language films

- 1940s British films