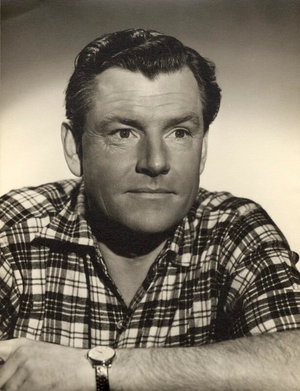

Kenneth More

Kenneth More | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Kenneth Gilbert More 20 September 1914 Gerrards Cross, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Died | 12 July 1982 (aged 67) |

| Other names | Kenny More |

| Years active | 1935–1980 |

| Spouses | {{Plainlist

Beryl Johnstone

(m. 1939; div. 1946)Mabel Barkby

(m. 1952; div. 1968) |

| Children | 2 |

| Website | http://www.kennethmore.com |

Kenneth Gilbert More, CBE (20 September 1914 – 12 July 1982) was an English film and stage actor.

Initially achieving fame in the comedy Genevieve (1953), he appeared in many roles as a carefree, happy-go-lucky gent. Films from this period include Doctor in the House (1954), Raising a Riot (1955), The Admirable Crichton (1957), The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw (1958) and Next to No Time (1958). He also played more serious roles as a leading man, beginning with The Deep Blue Sea (1955), Reach for the Sky (1956), A Night to Remember (1958), North West Frontier (1959), The 39 Steps (1959) and Sink the Bismarck (1960).

Although his career declined in the early 1960s, two of his own favourite films date from this time – The Comedy Man (1964) and The Greengage Summer (1961) with Susannah York, "one of the happiest films on which I have ever worked."[2] He also enjoyed a revival in the much-acclaimed TV adaptation of The Forsyte Saga (1967) and the Father Brown series (1974).

Early life

Kenneth More was born at 'Raeden', Vicarage Way, Gerrards Cross, Buckinghamshire,[3] the only son of Charles Gilbert More, a Royal Naval Air Service pilot, and Edith Winifred Watkins, the daughter of a Cardiff solicitor. He was educated at Victoria College, having spent part of his childhood in the Channel Islands, where his father was general manager of the Jersey Eastern Railway.

After he left school, he followed the family tradition by training as a civil engineer. He gave up his training and worked for a while in Sainsbury's on the Strand.

When More was 17 his father died, and he applied to join the Royal Air Force, but failed the medical test for equilibrium. He then travelled to Canada, intending to work as a fur trapper, but was sent back because he lacked immigration papers.

Windmill Theatre

On his return from Canada, a business associate of his father, Vivian Van Damm, agreed to offer him work as a stagehand at the Windmill Theatre, where his job included shifting scenery, and helping to get the nude players off stage during its Revudeville variety shows.[2] After a chance moment on stage helping out a comic, he realised he wanted to become an actor and was soon promoted to playing straight man in the Revudeville comedy routines, appearing in his first sketch in August 1935.

He played there for a year, which then led to regular work in repertory, including Newcastle, performing in plays such as Burke and Hare and Dracula's Daughter. Other stage appearances included Do You Remember? (1937), Stage Hands Never Lie (1937) and Distinguished Gathering (1937).

More continued his theatre work until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. He had the occasional bit part in films such as Look Up and Laugh (1935).

Second World War

Before the war More was working as an actor in Wolverhampton at the Rep and living at 166 Waterloo Road. According to the 1939 register he was also ambulance driver number 207; no doubt in anticipation of hostilities reaching the town.

More received a commission as a lieutenant in the Royal Navy, and saw active service aboard the cruiser HMS Aurora and the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious.

Resumption of acting career

On demobilisation in 1946 he worked for the Wolverhampton repertory company, then appeared on stage in the West End in And No Birds Sing (1946).

More played Badger in a TV adaptation of Toad of Toad Hall (1946) and a bit part in the film School for Secrets (1946). He was seen by Noël Coward playing a small role on stage in Power Without Glory (1947), which led to his being cast in Coward's Peace In Our Time (1948) on stage.[4]

More's earliest bit parts in films date from before the war, but around this time, he began to appear regularly on the big screen. For a small role in Scott of the Antarctic (1948) as Edward Evans, 1st Baron Mountevans, he was paid £500. He had minor parts in Man on the Run (1949), Now Barabbas (1949), and Stop Press Girl (1949).

Stardom

Rising reputation

More achieved a notable stage success in The Way Things Go (1950) with Ronald Squire, from whom More later claimed he learned his stage technique.[5]

He was in demand for minor roles on screen such as Morning Departure (1950) and Chance of a Lifetime (1950). More had a good part as a British agent in The Clouded Yellow (1950) for Ralph Thomas.[6]

He could also be seen in The Franchise Affair (1951) and The Galloping Major (1951). More's first Hollywood-financed film was No Highway in the Sky (1951) where he played a co-pilot. Thomas cast him in another strong support part in Appointment with Venus (1952).

More achieved above the title billing for the first time with a low budget comedy, Brandy for the Parson (1952), playing a smuggler.

The Deep Blue Sea

Roland Culver recommended More audition for a part in a new play by Terence Rattigan, The Deep Blue Sea (1952); he was successful and achieved tremendous critical acclaim in the role of Freddie.

During the play's run he appeared as a worried parent in a thriller, The Yellow Balloon (1953). He was in another Hollywood-financed film, Never Let Me Go (1953), playing a colleague of Clark Gable.

Film stardom: Genevieve and Doctor in the House

Director Henry Cornelius approached More during the run of The Deep Blue Sea and offered him £3,500 to play one of the four leads in a comedy, Genevieve (1953) (a part turned down by Guy Middleton). More said Cornelius never saw him in the play but cast him on the basis of his work in The Galloping Major.[7][8] More recalls "the shooting of the picture was hell. Everything went wrong, even the weather."[8] The resulting film was a huge success at the British box office.

More next made Our Girl Friday (1953) and Doctor in the House (1954), the latter for Ralph Thomas. Both films were made before the release of Genevieve so More's fee was relatively small; Our Girl Friday was a commercial disappointment but Doctor in the House was the biggest hit at the 1954 British box office[9] and the most successful film in the history of Rank. More received a BAFTA Award as best newcomer.

More appeared in a TV production of The Deep Blue Sea in 1954, which was seen by an audience of 11 million. More signed a five-year contract with Sir Alexander Korda at £10,000 a year.[10] '

He was now established as one of Britain's biggest stars and Korda announced plans to feature him in two films based on true stories, one about the Transatlantic flight of Alcock and Brown in 1919 also featuring Denholm Elliott,[10] and the other Clifton James, the double for Field Marshal Montgomery.[11] The first film was never made and the second (I Was Monty's Double) with another actor. Korda also wanted More to star in a new version of The Four Feathers, Storm Over the Nile (1956) but he turned it down.

However More did accept Korda's offer to appear in a film adaptation of The Deep Blue Sea (1955) gaining the Best Actor at the Venice Film Festival for his performance. The film was something of a critical and commercial disappointment (More felt Vivien Leigh was miscast in the lead) but still widely seen.[12] He also did the narration for Korda's The Man Who Loved Redheads (1955).

More starred in a comedy, Raising a Riot (1955), which was the eighth most popular movie at the British box office in 1955.[13]

Reach for the Sky

He received an offer from David Lean to play the lead role in an adaptation of The Wind Cannot Read by Richard Mason. More was unsure about whether the public would accept him in the part and turned it down, a decision he later regarded as "the greatest mistake I ever made professionally".[14] Lean dropped the project and was not involved in the eventual 1958 film version which starred Dirk Bogarde and which was directed by Ralph Thomas.

Instead, More played the Royal Air Force fighter ace, Douglas Bader, in Reach for the Sky (1956), a part turned down by Richard Burton. It was the most popular British film of the year. By 1956, More's asking price was £25,000 a film.[15]

More received offers to go to Hollywood, but turned them down, unsure his persona would be effective there. However, he started working with American co-stars and directors more often. In February 1957, he signed a contract with Daniel M. Angel and was to make ten films over five years, seven which would be distributed by Rank and three by 20th Century Fox.[16] In June of that year, he said:

Hollywood has been hitting two extremes – either a Biblical de Mille spectacular or a Baby Doll. Britain does two other kinds of movie as well as anyone – a certain type of high comedy and a kind of semi-documentary. I believe we (the British film industry) should hit these hard.[17]

His next film, The Admirable Crichton (1957), was a high comedy, based on the play by J. M. Barrie. It was released by Columbia Pictures. It was directed by Lewis Gilbert who also had made Reach for the Sky and who later said:

I was very fond of Kenny as an actor, although he wasn't particularly versatile. What he could do, he did very well. His strengths were his ability to portray charm; basically he was the officer returning from the war and he was superb in that kind of role. The minute that kind of role went out of existence, he began to go down as a box office star."[18]

Regarding his performance in this film, critic David Shipman wrote:

It was not just that he had superb comic timing: one could see absolutely why the family trusted their fates to him. No other British actor had come so close to that dependable, reliable quality of the great Hollywood stars – you would trust him through thick and thin. And he was more humorous than, say, Gary Cooper, more down-to-earth than, say, Cary Grant.[19]

The Admirable Crichton was the third most popular movie at the British box office in 1957.[20]

In 1957, More had announced that he would play the lead role of a captain caught up in the Indian Mutiny in Night Runners of Bengal but the film was never made.[17] More turned down an offer from Roy Ward Baker to play a German POW in The One That Got Away (1957), but agreed to play the lead part of Charles Lightoller in the Titanic film for the same director, A Night to Remember (1958). This was the first of a seven-year contract with Rank at a fee of £40,000 a film. It was popular though failed to recoup its large cost; it was one of More's most critically acclaimed films.[5]

For his next film, More had an American co-star Betsy Drake, Next to No Time (1958) directed by Cornelius. It was a minor success at the box office.

More then made a series of films for Rank that were distributed in the US by 20th Century Fox.

The first was The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw (1958), a Western spoof originally written for Clifton Webb. He had an American director (Raoul Walsh) and co-star (Jayne Mansfield), although the film was shot in Spain. It was the tenth most-popular movie at the British box office in 1958.[21]

He followed it for another with Ralph Thomas, a remake of The 39 Steps (1959), with a Hollywood co star (Taina Elg). It was a hit in Britain.[22]

The third Fox-Rank film was an Imperial adventure set in India, North West Frontier (1959), co-starring Lauren Bacall and directed by J. Lee Thompson. It was another success in Britain but not in the US.[23]

However Sink the Bismarck! (1960), directed by Gilbert, was a hit in Britain and the US.

More was the subject of This Is Your Life in 1959 when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews at the Odeon Cinema, Shepherd's Bush.

Later career

Decline in film popularity

In 1960, Rank's Managing Director John Davis gave permission for More to work outside his contract to appear in The Guns of Navarone (1961). More, however, made the mistake of heckling and swearing at Davis at a BAFTA dinner at the Dorchester, losing both the role (which went to David Niven) and his contract with Rank.[2]

More went on to make a comedy, Man In The Moon (1960), which flopped at the box office, "his first real flop" since becoming a star, according to Shipman.[5] He returned to the stage directing The Angry Deep in Brighton in 1960.

More and Gilbert were reunited on The Greengage Summer (1961) which remains one of More's favourite films, although Gilbert felt the star was miscast.

More says he accepted the lead in the low-budget youth film, Some People (1962), because he had no other offers at the time. The movie was profitable.[24] He was one of many stars in The Longest Day (1962) and played the lead in a comedy We Joined the Navy (1962), which was poorly received.

More tried to change his image with The Comedy Man (1963), which the public did not like, although it became his favourite role.

Some felt More's popularity declined when he left his second wife to live with Angela Douglas.[25] Film writer Andrew Spicer thought that "More's persona was so strongly associated with traditional middle class values that his stardom could not survive the shift towards working class iconoclasts" during that decade.[26] Another writer, Christopher Sandford, felt that "as the sixties began and the star of the ironic, postmodernist school rose, More was derided as a ludicrous old fogey with crinkly hair and a tweed jacket."[27]

More went back to the stage, appearing in Out of the Crocodile (1963) and Our Man Crichton (1964–65), which ran for six months.

He appeared in a 35-minute prologue to The Collector (1965) at the special request of director William Wyler, but it ended up being removed entirely from the final film.[5]

Revival

More's popularity recovered in the 1960s through West End stage performances and television roles, especially following his success in The Forsyte Saga (1967).[28] Critic David Shipman said More's personal notices for his performance on stage in The Secretary Bird (1968) "must be among the best accorded any light comedian during this century".[19]

On screen More had a small role in Dark of the Sun (1968) and a bigger one in Fräulein Doktor (1969). He was one of many names in Oh! What a Lovely War (1969) and Battle of Britain (1969). He took the role of the Ghost of Christmas Present in Scrooge (1970) and had long stage runs with a revival of The Winslow Boy (1970) and Getting On by Alan Bennett (1971).

He was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 1970 New Year Honours.[29]

Later career

More's later stage appearances included Signs of the Times (1973) and On Approval (1977). He played the title character in ATV's Father Brown (1974) series.

His later film roles included The Slipper and the Rose (1976), Where Time Began (1977), The Fabulous Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1977), Leopard in the Snow (1978), An Englishman's Castle (1978) and Unidentified Flying Oddball (1979).

Personal life

More was married three times. His first marriage in 1940 to actress Mary Beryl Johnstone (one daughter, Susan Jane, born 1941) ended in divorce in 1946. He married Mabel Edith "Bill" Barkby in 1952 (one daughter, Sarah, born 1954) but left her in 1968 for Angela Douglas, an actress (born, like More, in Gerrards Cross) 26 years his junior, causing considerable estrangement from friends and family. He was married to Douglas (whom he nicknamed "Shrimp") from 17 March 1968 until his death.[2]

More wrote two autobiographies, Happy Go Lucky (1959) and More or Less (1978). In the second book, he related how he had since childhood, a recurrent dream of something akin to a huge wasp descending towards him. During the war, he had experienced a German Stuka dive-bomber descending in just such a manner. After that, he claimed never to have had that dream again. Producer Daniel M. Angel successfully sued More for libel in 1980, over comments made in his second autobiography.[30]

Illness and death

More and Douglas separated for several years during the 1970s, but reunited when he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. This made it increasingly difficult for him to work, although his last role was a sizeable supporting part in a US TV adaptation of A Tale of Two Cities (1980). In 1980, when he was being sued by producer Danny Angel for comments in his memoirs, he told the court he was retired.[31]

In 1981, he wrote:

Doctors and friends ask me how I feel. How can you define "bloody awful?" My nerves are stretched like a wire; the simplest outing becomes a huge challenge – I have to have Angela's arm to support me most days... my balance or lack of it is probably my biggest problem. My blessings are my memories and we have a few very loyal friends who help us through the bad days... Financially all's well. Thank goodness my wife, who holds nothing of the past over my head, is constantly at my side. Real love never dies. We share a sense of humour which at times is vital. If I have a philosophy it is that life doesn't put everything your way. It takes a little back. I strive to remember the ups rather than the downs. I have a lot of time with my thoughts these days and sometimes they hurt so much I can hardly bear it. However, my friends always associate me with the song: "When You're Smiling..." lt isn't always easy but I'm trying to live up to it.[30]

More died on 12 July 1982, aged 67. It is now believed that he had been suffering from multiple system atrophy (MSA), a belief due in part to the age of onset and the speed at which the condition progressed.[32] He was cremated at Putney Vale Crematorium and a plaque erected at the actors' church St Paul's, Covent Garden, following a memorial attended by family, friends and colleagues.

Legacy

The Kenneth More Theatre, named in honour of the actor, was founded in 1975, in Ilford, east London.[33]

A plaque commemorates More at 27 Rumbold Road, Fulham, his home at the time of his death.[34] Another memorial plaque was installed at the Duchess Theatre in London's West End (where More gave his acclaimed performance as Freddie Page in a production of Terence Rattigan's The Deep Blue Sea).

Filmography

- Look Up and Laugh (1935) (bit part, uncredited)

- Carry On London (1937) (bit part, uncredited)

- The Silence of the Sea (1946, TV movie) as The German

- School for Secrets (1946) as Bomb Aimer (uncredited)

- Toad of Toad Hall (1946, TV movie) as Mr. Badger

- Scott of the Antarctic (1948) as Lt. E.G.R.(Teddy) Evans R.N.

- Man on the Run (1949) as Corp. Newman the Blackmailer

- Now Barabbas (1949) as Spencer

- Stop Press Girl (1949) as Police Sgt. 'Bonzo'

- For Them That Trespass – (1949) – Prison Warder

- Morning Departure (1950) as Lieut. Cmdr. James

- Chance of a Lifetime (1950) as Adam

- The Clouded Yellow (1951) as Willy Shepley

- The Franchise Affair (1951) as Stanley Peters

- The Galloping Major (1951) as Rosedale Film Studio Director

- No Highway in the Sky (1951) Dobson, Co-Pilot (uncredited)

- Appointment with Venus (1951) as Lionel Fallaize

- Brandy for the Parson (1952) as Tony Rackhman

- The Yellow Balloon (1953) as Ted

- Never Let Me Go (1953) as Steve Quillan

- Genevieve (1953) as Ambrose Claverhouse

- Our Girl Friday (1953) as Pat Plunkett

- Doctor in the House (1954) as Richard Grimsdyke

- The Deep Blue Sea (1954, BBC, TV movie) as Freddie Page

- The Man Who Loved Redheads (1955) as Narrator

- Raising a Riot (1955) as Tony Kent

- The Deep Blue Sea (1955) as Freddie Page

- Reach for the Sky (1956) as Douglas Bader

- The Admirable Crichton (1957) as Bill Crichton

- A Night to Remember (1958) as Second Officer Charles Herbert Lightoller

- Next to No Time (1958) as David Webb

- The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw (1958) as Jonathan Tibbs

- The Thirty-Nine Steps (1959) as Richard Hannay

- North West Frontier (1959) as Captain Scott

- Sink the Bismarck! (1960) as Captain Shepard

- Man in the Moon (1960) as William Blood

- The Greengage Summer (1961) as Eliot

- Heart to Heart (1962, TV movie) as David Mann

- Some People (1962) as Mr. Smith

- The Longest Day (1962) as Captain Colin Maud

- We Joined the Navy (1962) as Lt. Cmdr. Robert Badger

- The Comedy Man (1964) as Chick Byrd

- The Collector (1965) (uncredited)

- Lord Raingo (1966, TV movie) as Sam Raingo

- The Forsyte Saga (1967, TV series) as 'Young Jolyon' Forsyte

- The White Rabbit (1967, TV movie) as Wing Cmdr. Yeo-Thomas

- Dark of the Sun, also known as The Mercenaries (1968) as Doctor Wreid

- Fräulein Doktor (1969) as Col. Foreman

- Oh! What a Lovely War (1969) as Kaiser Wilhelm II

- Battle of Britain (1969) as Group Captain Barker

- Scrooge (1970) as Ghost of Christmas Present

- Father Brown (1974, TV series) as Father Brown

- The Slipper and the Rose: The Story of Cinderella (1976) as Chamberlain

- Where Time Began (1977) as Prof. Otto Linderbrock

- Leopard in the Snow (1978) as Sir Philip James

- An Englishman's Castle (1978, TV movie) as Peter Ingram

- The Spaceman and King Arthur (1979) as King Arthur

- A Tale of Two Cities (1980, TV movie) as Dr. Jarvis Lorry (final film role)

Unfilmed projects

- Adaptation of Nightrunners of Bengal (1957)[35]

- The Angry Silence (1960) – turned down role eventually played by Richard Attenborough[36]

Selected theatre credits

- Windmill Theatre – 1935

- Do You Remember? – Barry O’Brien Touring Company, August–November 1937

- Stage Hands Never Lie by Olive Remple – November 1937

- Stage Distinguished Gathering by James Parish – Wimbledon Theatre, August 1937

- And No Birds Sing by Rev Arthur Platt – Aldwych Theatre, November 1946[37]

- Power Without Glory – February–April 1947

- Peace In Our Time by Noël Coward – Lyric Theatre, July 1948

- The Way Things Go – Phoenix Theatre, May 1950

- The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan – Duchess Theatre, March 1952

- The Angry Deep – Brighton, January 1960 – Brighton – director only

- Out of the Crocodile – Phoenix Theatre, October 1963

- Our Man Crichton – Shaftesbury Theatre, December 1964 – ran six months

- The Secretary Bird – Savoy Theatre, October 1968

- The Winslow Boy by Terence Rattigan – New Theatre, November 1970 – ran nine months

- Getting On by Alan Bennett – Queen's Theatre, October 1971 – ran nine months

- Signs of the Times by Jeremy Kingston – Vaudeville Theatre, June 1973

- Kenneth More Requests the Pleasure of Your Company – Kenneth More Theatre, April 1977 – an evening of poetry, prose and music

- On Approval – Vaudeville Theatre, June 1977

Writings

- Happy Go Lucky (1959)

- Kindly Leave the Stage (1965)

- More or Less (1978)

Awards

- 1953 Nominated as Best British Actor (BAFTA) for Genevieve

- 1954 Won Best British Actor (BAFTA) for Doctor in the House

- 1955 Won Best Actor at Venice Film Festival for The Deep Blue Sea

- 1955 Won Most Promising International Star (Variety Club)

- 1955 Nominated Best British Actor (BAFTA) for The Deep Blue Sea

- 1956 Nominated Best British Actor (BAFT) for Reach for the Sky

- 1956 Won Picturegoer Magazine Best Actor Award for Reach for the Sky

- 1970 appointed a CBE in the New Year's Honours[29]

- 1974 Won TV Times Best Actor Award for Father Brown

- 1975 Recipient of silver heart for 40 Years in Showbusiness (Variety Club)

Box office ranking

British exhibitors regularly voted More one of the most popular stars at the local box office in an annual poll conducted by the Motion Picture Herald:[5]

- 1954 – 5th most popular British star

- 1955 – 5th most popular British star[38]

- 1956 – most popular international star[39]

- 1957 – 2nd most popular international star[40] (NB another source said he was the most popular[41])

- 1958 – 3rd most popular international star[42]

- 1959 – most popular British star[43]

- 1960 – most popular international star

- 1961 – 3rd most popular international star

- 1962 – 4th most popular international star[44]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "Search Results for England & Wales Deaths 1837-2007".

- ^ a b c d Kenneth More (1978) More or Less, Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-22603-X

- ^ "Kenneth More". London Remembers. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Popular new star" The Australian Women's Weekly (via National Library of Australia), 1 June 1955, p. 44. Retrieved: 6 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Shipman 1972, p. 371.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (29 May 1955). "From The 'Windmill' to the 'Sea'". New York Times. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ More 1978, p. 157.

- ^ a b Thompson, Harold. "From the 'Windmill' to the 'Sea'." The New York Times, 29 May 1955, p. 53.

- ^ "JOHN WAYNE HEADS BOX-OFFICE POLL". The Mercury. Vol. CLXXVI, no. 26, 213. Tasmania, Australia. 31 December 1954. p. 6. Retrieved 26 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "New British star has slick comedy flair". The Australian Women's Weekly. Vol. 22, no. 8. 21 July 1954. p. 34. Retrieved 26 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Herald features." The Sydney Morning Herald (via National Library of Australia), 9 September 1954, p. 11. Retrieved: 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Front page news ABROA stars share Venice film prize". The Argus. 12 September 1955. p. 2. Retrieved 6 May 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Dirk Bogarde favourite film actor". The Irish Times. Dublin, Ireland. 29 December 1955. p. 9.

- ^ More 1978, p. 228.

- ^ "Star Dust." The Mirror (Perth, WA) (via National Library of Australia), 11 February 1956, p. 11. Retrieved: 6 May 2012.

- ^ STEPHEN WATTS (3 February 1957). "OBSERVATIONS ON THE ENGLISH SCREEN SCENE: Presenting the New Producers' Chief --Annual Polls—Debated Features British Victors Controversies Potpourri". New York Times. p. 85.

- ^ a b Morgan, Gwen (14 July 1957). "Kenneth More- Britain's best: He's no matinee idol, but film fans around the world love him". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 22.

- ^ MacFarlane 1997, p. 222.

- ^ a b Shipman 1989, pp. 414–415.

- ^ "BRITISH ACTORS HEAD FILM POLL: BOX-OFFICE SURVEY". The Manchester Guardian. 27 December 1957. p. 3.

- ^ "Year of Profitable British Films". The Times. London, England. 1 January 1960. p. 13 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ "Year Of Profitable British Films". The Times. London, England. 1 January 1960. p. 13 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ "FOUR BRITISH FILMS IN 'TOP 6': BOULTING COMEDY HEADS BOX OFFICE LIST". The Guardian. London (UK). 11 December 1959. p. 4.

- ^ E. A. (19 July 1964). "LOCAL NEWS: BANKHEAD'S BACK, OTHER ITEMS". New York Times. ProQuest 115852896.

- ^ "An interview with Peter Yeldham." Memorable TV. Retrieved: 12 June 2012.

- ^ Spicer, Andrew. "Kenneth More." BFI Screenonline. Retrieved: 6 May 2012.

- ^ Sandford, Christopher. "Quiet Hero: Happy (Belated) Birthday to British Actor Kenneth More (September 20, 1914 – July 12, 1982)." Bright Lights Film Journal, 29 September 2014.

- ^ "TV's Father Brown." The Australian Women's Weekly (via National Library of Australia), 27 March 1974, p. 10. Retrieved: 6 May 2012.

- ^ a b "No. 44999". w:The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1970. p. 9.

- ^ a b "Why I'm living on Love." The Australian Women's Weekly (via National Library of Australia), 7 October 1981, p. 26. Retrieved: 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Kenneth More 'has retired'". The Guardian. London (UK). 2 May 1980. p. 3.

- ^ Kenneth More Charity page at official website.

- ^ Drama. British Theatre Association. 1975. p. 19.

- ^ "Plaque: Kenneth More". London Remembers. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ STEPHEN WATTS (27 March 1955). "'That Lady' Produces a New Star—Tax Relief Plea—Other Movie Matters". New York Times. p. X5.

- ^ McFarlane 1997, p. 36.

- ^ "ROYAL VISITORS AT THEATRE: Charity Performance in the Lyceum "AND NO BIRDS SING"". The Scotsman. Edinburgh, Scotland. 2 July 1946. p. 4.

- ^ "'The Dam Busters'". The Times. London, England. 29 December 1955. p. 12.

- ^ "More pleases". The Argus. 8 December 1956. p. 2. Retrieved 9 July 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "News in Brief". The Times. London, England. 27 December 1957.

- ^ "The Most Popular Film of the Year". The Times. No. 54022. London, England. 12 December 1957. p. 3.

- ^ "Mr. Guinness Heads Film Poll". The Times. London, England. 2 January 1959. p. 4.

- ^ "Year Of Profitable British Films". The Times. London, England. 1 January 1960. p. 13.

- ^ "Money-Making Films Of 1962". The Times. London, England. 4 January 1963. p. 4.

Bibliography

- McFarlane, Brian. An Autobiography of British Cinema. London: Methuen, 1997. ISBN 978-0-4137-0520-4.

- More, Kenneth. More or Less. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1978. ISBN 0-340-22603-X. Rights owned by the Kenneth More estate from 2019

- Pourgourides, Nick. More Please. London: Amazon, 2020. ISBN 979-8554548390. Authorized biography

- Sheridan Morley. "More, Kenneth Gilbert (1914–1982)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Shipman, David.The Great Movie Stars: The International Years. London: Angus & Robertson, 1989, 1st ed 1972. ISBN 0-7-5150-888-8.

- Sweet, Matthew.Shepperton Babylon: The Lost Worlds of British Cinema. London: Faber & Faber, 2005. ISBN 0-571-21297-2.

External links

- Kenneth More at IMDb

- Kenneth More at the BFI's Screenonline

- Kenneth More at TCM

- Kenneth More Theatre

Lua error in Module:Authority_control at line 182: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).

- Pages with script errors

- Pages containing London Gazette template with parameter supp set to y

- Articles with short description

- Use British English from July 2021

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Use dmy dates from July 2021

- Commons category link is defined as the pagename

- 1914 births

- 1982 deaths

- 20th-century English male actors

- Best British Actor BAFTA Award winners

- British male comedy actors

- Burials at Putney Vale Cemetery

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Neurological disease deaths in England

- Deaths from Parkinson's disease

- English male film actors

- English male stage actors

- English male television actors

- English people of Welsh descent

- People educated at Victoria College, Jersey

- People from Gerrards Cross

- Royal Navy officers of World War II

- Volpi Cup for Best Actor winners