Theatre of Blood: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox film | {{Infobox film | ||

| name = Theatre of Blood | | name = Theatre of Blood | ||

Revision as of 10:45, 2 September 2024

| Theatre of Blood | |

|---|---|

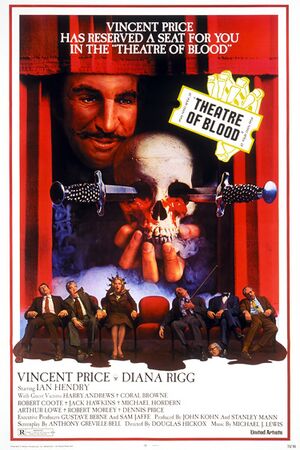

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Douglas Hickox |

| Written by | Anthony Greville-Bell (screenplay), Stanley Mann and John Kohn (idea) |

| Produced by | Gustave Berne Sam Jaffe John Kohn Stanley Mann |

| Starring | Vincent Price Diana Rigg Ian Hendry |

| Cinematography | Wolfgang Suschitzky |

| Edited by | Malcolm Cooke |

| Music by | Michael J. Lewis |

Production companies | Harbour Productions Limited Cineman Productions[1] |

| Distributed by | United Artists[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 104 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1 million (U.S./ Canada rentals)[2] |

Theatre of Blood (U.S. title: Theater of Blood) is a 1973 British horror comedy film directed by Douglas Hickox and starring Vincent Price and Diana Rigg.[3]

Plot

After being humiliated by members of the Theatre Critics Guild at an awards ceremony, Shakespearean actor Edward Kendal Sheridan Lionheart is seen committing suicide by diving into the Thames from a great height. He survives and is rescued by a group of vagrants. Two years later, beginning on the Ides of March, Lionheart sets out to exact vengeance against the critics who failed to acclaim his genius, killing them one by one in ways very similar to murder scenes in the season of William Shakespeare's plays that he last performed. Before each murder, Lionheart recites the critic's damning review of his performance in the role.

The first critic, George Maxwell, is repeatedly stabbed by a mob of murderous homeless people, suggested by the murder of Julius Caesar in Julius Caesar. The second, Hector Snipe, is impaled with a spear, and his body is dragged away to appear at Maxwell's funeral tied to a horse's tail, replicating the murder of Hector in Troilus and Cressida. The third, Horace Sprout, is decapitated while sleeping, as is Cloten in Cymbeline. The fourth critic, Trevor Dickman, has his heart cut out by Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, the play being rewritten so that Antonio is forced to repay his debt with a pound of flesh. The fifth, Oliver Larding, is drowned in a barrel of wine, as is George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence in Richard III.

For the next play, Romeo and Juliet, Lionheart lures the critic Peregrine Devlin to a fencing gymnasium, where he re-enacts the sword fight from the play. He badly wounds Devlin but chooses not to kill him at this juncture. The sixth critic to die, Solomon Psaltery, an obsessively jealous man, murders his wife Maisie, believing her to be unfaithful, as portrayed in Othello. Although Psaltery survives, his actions lead to his imprisonment, and he will likely die in prison. The seventh critic to die, Miss Chloe Moon, is electrocuted to replicate the burning of Joan of Arc in Henry VI, Part 1. The eighth critic to die, flamboyant gourmand Meredith Merridew, is force-fed pies made from the flesh of his two toy poodles until he chokes to death, replicating the demise of Queen Tamora in Titus Andronicus.

It is revealed that Lionheart is being aided by his adoring daughter Edwina. She kidnaps Devlin and brings him to the theatre, where Lionheart tells him to give him the award or be blinded with red-hot daggers, as happens to Gloucester in King Lear. He refuses, but the contraption meant to blind him gets stuck. Lionheart sets fire to the theatre. In the confusion, one of the vagrants kills Edwina by striking her on the head with the award statuette, unwittingly casting her in the role of Cordelia, Lear's youngest daughter. Lionheart retreats, carrying her body to the roof and delivering Lear's final monologue before the roof caves in, setting him ablaze and sending him to his death. Devlin, a critic even in the face of death, then gives Lionheart's performance a positive if mixed review.

Cast

- Vincent Price as Edward Lionheart

- Diana Rigg as Edwina Lionheart

- Ian Hendry as Peregrine Devlin

- Harry Andrews as Trevor Dickman

- Robert Coote as Oliver Larding

- Michael Hordern as George Maxwell

- Robert Morley as Meredith Merridew

- Coral Browne as Chloe Moon

- Jack Hawkins as Solomon Psaltery

- Arthur Lowe as Horace Sprout

- Dennis Price as Hector Snipe

- Milo O'Shea as Inspector Boot

- Eric Sykes as Sgt. Dogge

- Diana Dors as Maisie Psaltery

- Joan Hickson as Mrs. Sprout

- Renée Asherson as Mrs. Maxwell

- Madeline Smith as Rosemary

- Brigid Erin Bates as Agnes

- Charles Sinnickson as vicar

- Tutte Lemkow as meths drinker

- Declan Mulholland as meths drinker

- Stanley Bates as meths drinker

- John Gilpin as meths drinker

Like other movies in the last years of his life, Hawkins was dubbed by his friend Charles Gray. Both Hawkins and Dennis Price died within a few months of the film's release.

Production

The film was originally to be titled Much Ado About Murder.[4] Robert Fuest, director of The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) and its sequel Dr. Phibes Rises Again (1972), was originally offered this film to direct, but turned it down on the grounds of not wishing to be typed as "the guy who makes Vincent Price theme killing movies."[5]

Director Douglas Hickox said: "The cast was so good that all I had to do as director was open the dressing room door and let the cameras roll."[6]

Theatre of Blood was filmed entirely on location. Lionheart's hideout, the "Burbage Theatre", was the Putney Hippodrome, which was built in 1906, but had been vacant and dilapidated for more than ten years before it was used in the film.[citation needed] It was demolished in 1975 to make way for housing.

Lionheart's tomb is a Sievier family monument in Kensal Green Cemetery, showing a seated man, one hand placed on the head of a woman kneeling in adoration, while the other holds the Bible, its pages opened to a passage from the Gospel of Luke. The monument was altered for the film by substituting plaster masks of Price and Rigg for the real faces, replacing the Bible with a volume of Shakespeare, and adding Lionheart's name and dates.[citation needed]

Peregrine Devlin's Thames-side apartment is the penthouse flat at Alembic House (now known as Peninsula Heights) on the Albert Embankment.[7] At the time of filming, the property belonged to the actor and film producer Stanley Baker.[8] It is now the London home of novelist and disgraced politician Jeffrey Archer.[9]

When pre-production commenced, Coral Browne insisted that she would wear only clothing designed by Jean Muir. The film's costume designer, Michael Baldwin, informed Browne that the budget could not possibly stretch to designer clothing for any of the cast. Baldwin was surprised and angered to get a call from Douglas Hickox after he had had a meeting with Browne, telling him that she could have the dresses she requested, increasing the budget solely to accommodate her demands. Baldwin was further infuriated to discover that Browne kept all the dresses after filming wrapped.[10]

"Young Man Among Roses", the miniature featured in the introduction and used as the model for the Critics' Award Statuette, is by the Elizabethan portraitist Nicolas Hilliard.

This film was reportedly a favourite of Vincent Price's, as he had always wanted the chance to act in Shakespeare.[11] Before or after each death in the film, Lionheart recites passages of Shakespeare, giving Price an outlet to deliver such speeches as Hamlet's third soliloquy ("To be, or not to be, that is the question..."); Mark Antony's eulogy for Caesar from Julius Caesar ("Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears..."); "Now is the winter of our discontent..." from the beginning of Richard III; and the raving of King Lear after the death of his faithful daughter.

Diana Rigg regarded Theatre of Blood as her best film.[citation needed]

The film is sometimes considered to be a spoof or homage of The Abominable Dr. Phibes.[12][13] Similarities with the earlier film include a protagonist who is presumed dead and is seeking revenge; nine intended victims, one of whom works directly with Scotland Yard and survives; themed murders rooted in literature; and a young female sidekick.

Critical reception

Theatre of Blood maintains an 88% "fresh" approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes from 40 reviews with the Critics consensus "Deliciously campy and wonderfully funny, Theater of Blood features Vincent Price at his melodramatic best."

The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "Although his schematic vengeance invites comparison with that of the Abominable Dr. Phibes, ... Edward Lionheart happily turns out to be a villain of infinitely higher calibre. ... Douglas Hickox's direction is fairly adroit: he makes effective use of locations, and a constantly moving camera prevents the brazen theatricality of the whole scheme becoming too overt. He also sustains a reasonable amount of tension by keeping the murders on the level of grand guignol rather than farce; but in order to sustain our interest, it would have been necessary to reserve some surprises for the last third of the film, and here both script and direction begin to flag. The killing of Meredith Merridrew (Robert Morley) by forcing him to eat his pet poodles remains merely unpleasant, though Lionheart has by this time become such a generally sympathetic character that the conventional denouement is both tedious and irritating. Indeed, Price's superb antics have so effectively upstaged the other performers that the last remaining critic's refusal to alter his original judgment emerges as an act of crass stupidity rather than courage."[15]

The Los Angeles Times called it "quite possibly the best horror film Vincent Price has ever made. Certainly it affords him the best role he has ever had in the genre. A triumph of witty, stylish Grand Guignol, it allows Price to range richly between humour and pathos."[16]

Stage adaptation

The film was adapted for the stage by the British company Improbable, with Jim Broadbent playing Edward Lionheart and Rachael Stirling (Diana Rigg's daughter), playing Lionheart's daughter. The play differs from the film in that the critics are from British newspapers, including The Guardian and The Times, and the only set is an abandoned theatre. The play is again set in the 1970s, rather than being updated.[17] Most of the secondary characters were excised, including police, and the number of deaths reduced. The killings based on Othello and Cymbeline are omitted as they would have to take place outside the theatre and rely on secondary characters, such as the critics' wives. The name of Lionheart's daughter is changed from "Edwina" to "Miranda" to enhance the Shakespearean influence. The adaptation ran in London at the National Theatre between May and September 2005 and received mixed reviews.[18]

Vincent Price and Coral Browne

Diana Rigg introduced Vincent Price to his future wife Coral Browne during the making of the film. Browne recalled in a television documentary Caviar to the General in 1990 that she had not wanted to make "one of those scary Vincent Price movies", but she was persuaded to take the part of Chloe Moon by her friends Robert Morley and Michael Hordern, acknowledging that the film thus had a very strong cast. Rigg was unaware that Price was married.[10]

References

- ^ a b "Theatre of Blood". BFI. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973", Variety, 9 January 1974, p. 60

- ^ "Theatre of Blood". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (September 7, 2020). "A Tale of Two Blondes: Diana Dors and Belinda Lee". Filmink.

- ^ Humpreys, Justin (2018). The Dr. Phibes Companion: The Morbidly Romantic History of the Classic Vincent Price Horror Film Series. Bear Manor Media. p. 180. ISBN 9781629332949.

- ^ Iverson, Mark (April 2020). Vincent Price: The British Connection. Telos Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-84583-136-3.

- ^ James, Simon (2007). London Film Location Guide. Chrysalis Books. p. 146.

- ^ Fuller, Peter (9 September 2014). "Theatre of Blood Locations Guide". www.spookyisles.com. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Denyer, Lucy (2006-12-17). "Good day at the office". The Sunday Times. Times Newspapers. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ^ a b Collis, Rose (October 2007). Coral Browne: "This Effing Lady". Oberon Books. ISBN 978-1-84002-764-8.

- ^ Gary J. Svehla and Susan Svehla, Vincent Price Midnight Marquee Actors Series, ISBN 1-887664-21-1, p. 267

- ^ "Theater Of Blood". Eccentric Cinema. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- ^ "Theatre of Blood". Tcm.com. Retrieved 2023-12-29.

- ^ Strong (1983), pp.9 and 156–157, gives the identity of this painting as "almost certainly" the Earl of Essex.

- ^ "Theatre of Blood". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 40 (468): 132. 1 January 1973 – via ProQuest.

- ^ MOVIE REVIEW: Critics Killed Off in 'Blood', Thomas, Kevin. Los Angeles Times, 20 April 1973: h21.

- ^ "Show Detail". Improbable. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Billington, Michael (May 20, 2005). "Review Theatre of Blood". The Guardian.

External links

- Theatre of Blood at IMDb

- Theatre of Blood at the TCM Movie Database

- Theatre of Blood at Rotten Tomatoes

- Theatre of Blood at Letterbox DVD

- 2005 National Theatre Production

- Putney Hippodrome at Cinema Treasures

- Photo of Putney Hippodrome

- Theatre of Blood then-and-now location photographs at ReelStreets

- Articles with short description

- Template film date with 1 release date

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2023

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2024

- IMDb title ID not in Wikidata

- Rotten Tomatoes ID not in Wikidata

- 1973 films

- 1973 comedy horror films

- 1973 black comedy films

- 1970s serial killer films

- 1970s exploitation films

- British comedy horror films

- British black comedy films

- British serial killer films

- Films directed by Douglas Hickox

- Films based on works by William Shakespeare

- Films shot in London

- Films about actors

- Films set in the 1970s

- British films about revenge

- United Artists films

- Films adapted into plays

- Films set in 1970

- Films set in 1972

- Films with screenplays by Stanley Mann

- Films produced by Stanley Mann

- British exploitation films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s British films

- Films scored by Michael J. Lewis (composer)