Jonathan Cecil: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox person | {{Infobox person | ||

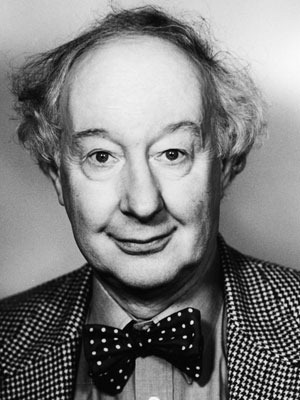

| image = Jonathan Cecil.jpg | | image = Jonathan Cecil.jpg | ||

| caption = | | caption = | ||

| birth_name = Jonathan Hugh Gascoyne-Cecil | | birth_name = Jonathan Hugh Gascoyne-Cecil | ||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1939|02|22|df=y}} | | birth_date = {{birth date|1939|02|22|df=y}} | ||

| birth_place = [[ | | birth_place = [[London]], England | ||

| death_date = {{death date and age|2011|09|22|1939|02|22|df=y}} | | death_date = {{death date and age|2011|09|22|1939|02|22|df=y}} | ||

| death_place = [[ | | death_place = [[Charing Cross Hospital|Charing Cross Hospital, London]], England | ||

| othername = | | othername = | ||

| occupation = Actor | | occupation = Actor | ||

| yearsactive = 1963–2011 | | yearsactive = 1963–2011 | ||

| spouse = | | spouse = | ||

*{{Marriage|[[ | *{{Marriage|[[Vivien Heilbron|Vivien Heilbron]]|1963|1975|end=div}} | ||

*{{Marriage|Anna Sharkey|1976|2011}} | *{{Marriage|Anna Sharkey|1976|2011}} | ||

| website = | | website = | ||

}} | }} | ||

'''Jonathan Hugh Gascoyne-Cecil''' (22 February 1939 – 22 September 2011), known as '''Jonathan Cecil''', was an English [[ | '''Jonathan Hugh Gascoyne-Cecil''' (22 February 1939 – 22 September 2011), known as '''Jonathan Cecil''', was an English [[theatre|theatre]], [[film|film]], and [[television|television]] [[actor|actor]]. | ||

==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

Cecil was born in [[ | Cecil was born in [[London|London]], England, the son of [[Lord David Cecil|Lord David Cecil]] and the grandson of the [[James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury|4th Marquess of Salisbury|]]. His other grandfather was the literary critic [[Desmond MacCarthy|Sir Desmond MacCarthy]]. He was the great-grandson of Conservative [[Prime Minister|Prime Minister]] [[Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury|The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury]]. | ||

Brought up in [[ | Brought up in [[Oxford]], where his father was Goldsmith Professor of English, he was educated at [[Eton College|Eton]], where he played small parts in school plays and at [[New College, Oxford]], where he read [[modern languages]], specialising in [[French language|French]] and continued with amateur dramatics.<ref name=gore>{{cite news |url=https://www.questia.com/magazine/1P3-1080501431/floreat-etona |title=Floreat Eton |first=Robert |last=Gore-Langton |work=[[The Spectator|The Spectator]] |date=2006-07-08 |accessdate=2019-03-02}}</ref><ref name=theatrearchive>[http://www.bl.uk/projects/theatrearchive/cecil.html Interview with Jonathan Cecil] at bl.uk</ref> | ||

At Oxford, his friends included [[Dudley Moore]] and [[Alan Bennett]].<ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/culture-obituaries/tv-radio-obituaries/8913990/Jonathan-Cecil.html |title=Jonathan Cecil |author=Staff writers |work=[[The Daily Telegraph]] |date=2011-11-24 |accessdate=2019-03-02}}</ref> In a production of [[Ben Jonson]]'s ''[[Bartholomew Fair: A Comedy|Bartholomew Fair]]'', he played a [[lunatic]] called Troubadour and a woman who sells pigs.<ref name=theatrearchive/> Of his early acting at Oxford, Cecil said {{quote|I was still stiff and awkward, but this was rather effective for [[comedy|comedy parts]], playing sort of comic servants in plays, and in the [[cabaret]] nights we had.<ref name=theatrearchive/>}} | At Oxford, his friends included [[Dudley Moore]] and [[Alan Bennett]].<ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/culture-obituaries/tv-radio-obituaries/8913990/Jonathan-Cecil.html |title=Jonathan Cecil |author=Staff writers |work=[[The Daily Telegraph]] |date=2011-11-24 |accessdate=2019-03-02}}</ref> In a production of [[Ben Jonson]]'s ''[[Bartholomew Fair: A Comedy|Bartholomew Fair]]'', he played a [[lunatic]] called Troubadour and a woman who sells pigs.<ref name=theatrearchive/> Of his early acting at Oxford, Cecil said {{quote|I was still stiff and awkward, but this was rather effective for [[comedy|comedy parts]], playing sort of comic servants in plays, and in the [[cabaret]] nights we had.<ref name=theatrearchive/>}} | ||

| Line 94: | Line 87: | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

*{{IMDb name | id = 0147699}} | *{{IMDb name | id = 0147699}} | ||

*Jonathan Cecil, ''[http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/the_tls/article3319135.ece In the dressing room with Noel Coward]'' from ''[[ | *Jonathan Cecil, ''[http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/the_tls/article3319135.ece In the dressing room with Noel Coward]'' from ''[[Times Literary Supplement|Times Literary Supplement]]'' of 6 February 2008, text online | ||

*Jonathan Cecil, [https://web.archive.org/web/20100825152150/http://www.spectator.co.uk/spectator/thisweek/21077/very-much-his-own-man.thtml Very much his own man], from ''[[ | *Jonathan Cecil, [https://web.archive.org/web/20100825152150/http://www.spectator.co.uk/spectator/thisweek/21077/very-much-his-own-man.thtml Very much his own man], from ''[[The Spectator]]'' of 18 September 2004, text online | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cecil, Jonathan}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Cecil, Jonathan}} | ||

Latest revision as of 15:48, 18 February 2023

Jonathan Cecil | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jonathan Hugh Gascoyne-Cecil 22 February 1939 London, England |

| Died | 22 September 2011 (aged 72) Charing Cross Hospital, London, England |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1963–2011 |

| Spouses |

Anna Sharkey (m. 1976–2011) |

Jonathan Hugh Gascoyne-Cecil (22 February 1939 – 22 September 2011), known as Jonathan Cecil, was an English theatre, film, and television actor.

Early life

Cecil was born in London, England, the son of Lord David Cecil and the grandson of the 4th Marquess of Salisbury|. His other grandfather was the literary critic Sir Desmond MacCarthy. He was the great-grandson of Conservative Prime Minister The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury.

Brought up in Oxford, where his father was Goldsmith Professor of English, he was educated at Eton, where he played small parts in school plays and at New College, Oxford, where he read modern languages, specialising in French and continued with amateur dramatics.[1][2]

At Oxford, his friends included Dudley Moore and Alan Bennett.[3] In a production of Ben Jonson's Bartholomew Fair, he played a lunatic called Troubadour and a woman who sells pigs.[2] Of his early acting at Oxford, Cecil said

I was still stiff and awkward, but this was rather effective for comedy parts, playing sort of comic servants in plays, and in the cabaret nights we had.[2]

After Oxford, he spent two years training for an acting career at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, where he was taught (amongst others) by Michael MacOwan and Vivian Matalon and where his contemporaries included Ian McKellen and Derek Jacobi.[2]

Career

Cecil's first television appearance was in playing a leading role opposite Vanessa Redgrave in "Maggie", an episode of the BBC television series First Night transmitted in February 1964, which he later called "a baptism by fire because I was being seen by half the nation". After that he spent eighteen months in repertory at Salisbury, of which he later commented, "You learnt how to make an entrance and make an exit." His parts at Salisbury included the Dauphin in Saint Joan, Disraeli in Portrait of a Queen, Trinculo in The Tempest, and "all the Shakespeare".[2]

His first West End part came in May 1965 in Julian Mitchell's dramatisation of A Heritage and Its History at the Phoenix, in which he got good notices, and his next was in a Beaumont production of Peter Ustinov's Half-Way up the Tree, directed by Sir John Gielgud.[2]

In film and television, Cecil almost always played upper class English characters. His screen work included the roles of Cummings in The Diary of a Nobody (1964), Captain Cadbury in the Dad's Army episode "Things That Go Bump in the Night" (1973), Bertie Wooster in Thank You, P.G. Wodehouse (1981), Ricotin in Federico Fellini's And the Ship Sails On (1983), and Captain Hastings (to Peter Ustinov's Hercule Poirot) in Thirteen at Dinner (1985), Dead Man's Folly and Murder in Three Acts (both 1986).[4] He has been called "one of the finest upper-class-twits of his era".[1] In 2009 he appeared in an episode of Midsomer Murders.[4]

He also worked in radio, where his credits included The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and The Brightonomicon. He also appeared in The Next Programme Follows Almost Immediately, playing characters with very bad foreign accents. Additionally, he stood in for Derek Nimmo in the role of the Bishop's Chaplain, the Reverend Mervyn Noote, in the second series of the radio episodes of the ecclesiastical sitcom All Gas and Gaiters, which ran for twenty episodes. In the series of adaptations from P. G. Wodehouse What Ho! Jeeves (1973–81) he played the recurring character Bingo Little.

He narrated audio books of many of P. G. Wodehouse's books, performing voice characterisations for each character, and becoming possibly the most known narrator to ever perform the series.

Cecil wrote occasionally for The Spectator and The Times Literary Supplement. In one piece he noted

Handsome young male actors of the older school have tended, in my experience, to be somewhat vapid and vain. I write this in no spirit of envy — comic and character actors, like proverbial blondes, usually have more fun.[5]

He also admitted that "most of my experience has been in comedy, that’s the way life has taken me ... if I have any regrets, it’s that I didn’t do parts with more depth".[2]

Personal life

Cecil was married twice. He met actress Vivien Heilbron when they were both studying at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, and the couple married in 1963.[6] They were divorced after he met the actress Anna Sharkey while appearing at London's Mermaid Theatre in 1972; he and Sharkey married in 1976.[6]

Cecil died from pneumonia on 22 September 2011 at Charing Cross Hospital in London, aged 72. He had suffered from emphysema.[6][7]

Filmography

- Nothing But the Best (1964) – Guards Officer (uncredited)

- The Ordeal of Richard Feverel (1964) – Giles Jinkson

- The Yellow Rolls-Royce (1964) – Young Man (uncredited)

- The Great St Trinian's Train Robbery (1966) – Man (uncredited)

- Otley (1968) – Young Man at Party

- The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer (1970) – Spot

- Lust for a Vampire (1971) – Biggs

- To Catch a Spy (1971) – British Attaché

- Up the Front (1972) – Captain Nigel Phipps Fortescue

- Are You Being Served (1975) – Customer

- Barry Lyndon (1975) – Lt. Jonathan Fakenham

- Under the Doctor (1976) – Rodney Harrington-Harrington / Lord Woodbridge

- Joseph Andrews (1977) – Fop One

- Rising Damp (1980) – Boutique Assistant

- History of the World, Part I (1981) – Poppinjay (The French Revolution)

- Farmers Arms (1983) – Mr. Brown

- And the Ship Sails On (1983) – Ricotin

- The Wind in the Willows (1983) – (voice)

- Thirteen at Dinner (1985) – Captain Hastings

- Dead Man's Folly (1986) – Captain Hastings

- Murder in Three Acts (1986) – Captain Hastings

- The Second Victory (1987) – Capt. Lowell

- Little Dorrit (1987) – Magnate on the Bench

- Hot Paint (1988) – Earl of Lanscombe

- The Fool (1990) – Sir Martin Locket

- A Fine Romance (1992)

- As You Like It (1992) – Lord

- Day Release (1997)

- RPM (1998) – Lord Baxter

- Fakers (2004) – Dr Fielding

- Van Wilder: The Rise of Taj (2006) – Provost Cunningham

References

- ^ a b Gore-Langton, Robert (2006-07-08). "Floreat Eton". The Spectator. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g Interview with Jonathan Cecil at bl.uk

- ^ Staff writers (2011-11-24). "Jonathan Cecil". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- ^ a b Jonathan Cecil at IMDb

- ^ Cecil, Jonathan (2004-11-13). "A modest triumph". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 2010-08-25. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- ^ a b c Billington, Michael (2011-09-25). "Jonathan Cecil obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- ^ Staff writers (2011-09-24). "Jonathan Cecil". The Times. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

External links

- Jonathan Cecil at IMDb

- Jonathan Cecil, In the dressing room with Noel Coward from Times Literary Supplement of 6 February 2008, text online

- Jonathan Cecil, Very much his own man, from The Spectator of 18 September 2004, text online

- Pages with script errors

- 1939 births

- 2011 deaths

- Male actors from London

- Alumni of New College, Oxford

- Alumni of the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art

- English male film actors

- English male television actors

- English male stage actors

- People educated at Eton College

- People educated at The Dragon School

- 20th-century English male actors

- 21st-century English male actors