The Abominable Dr. Phibes: Difference between revisions

m (1 revision imported) |

(→Music) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox film | {{Infobox film | ||

| name = The Abominable Dr. Phibes | | name = The Abominable Dr. Phibes | ||

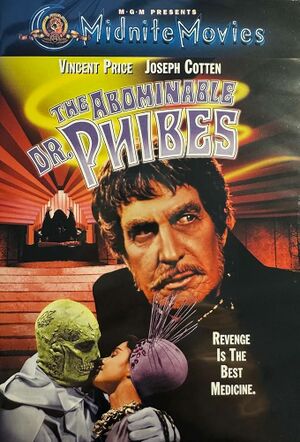

| image = Abominablephibes1.jpg | | image = Abominablephibes1.jpg | ||

| alt = | | alt = | ||

| caption = | | caption = | ||

| director = [[Robert Fuest]] | | director = [[Robert Fuest]] | ||

| writer = {{Plainlist| | | writer = {{Plainlist| | ||

| Line 78: | Line 75: | ||

The film's [[Film score|incidental score]] was composed by [[Basil Kirchin]] and includes 1920s-era [[source music]], most notably "[[Charmaine (song)|Charmaine]]" and "[[Darktown Strutters' Ball]]". | The film's [[Film score|incidental score]] was composed by [[Basil Kirchin]] and includes 1920s-era [[source music]], most notably "[[Charmaine (song)|Charmaine]]" and "[[Darktown Strutters' Ball]]". | ||

[[File:Dr Phibes LP cover. | [[File:Dr Phibes LP cover.webp|thumb|right|''Dr. Phibes'' 1971 soundtrack LP]] | ||

One of several music-related errors or anachronisms within the film's storyline is the song overlaid as a recorded performance by one of the ostensibly mechanized musicians of "Dr. Phibes' Clockwork Wizards."<ref>[https://www.facebook.com/DrPhibesClockworkWizards "Dr. Phibes Clockwork Wizards"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150319105612/https://www.facebook.com/DrPhibesClockworkWizards |date=19 March 2015 }}.</ref> The pianist in this simulated [[Animatronics|animatronic]] band "sings" "[[One for My Baby (and One More for the Road)]]". Although the film's plot is set in England in the 1920s, this particular song did not exist until 1943, when [[Harold Arlen]] and [[Johnny Mercer]] wrote it as part of their film score for ''[[The Sky's the Limit (1943 film)|The Sky's the Limit]]''. [[Fred Astaire]] sang the [[jazz standard]] for the first time in that musical comedy. Likewise, the melody of the song "[[You Stepped Out of a Dream]]", written by [[Nacio Herb Brown]] (music) and [[Gus Kahn]] (lyrics) and first published in 1940, accompanies a scene depicting Dr. Phibes and Vulnavia dancing together in the ballroom of his mansion. Other musical anachronisms are Vulnavia's playing "[[Close Your Eyes (Bernice Petkere song)|Close Your Eyes]]" (1933) on the violin, or her placing in a car a music box that plays "[[Elmer's Tune]]" (1941). | One of several music-related errors or anachronisms within the film's storyline is the song overlaid as a recorded performance by one of the ostensibly mechanized musicians of "Dr. Phibes' Clockwork Wizards."<ref>[https://www.facebook.com/DrPhibesClockworkWizards "Dr. Phibes Clockwork Wizards"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150319105612/https://www.facebook.com/DrPhibesClockworkWizards |date=19 March 2015 }}.</ref> The pianist in this simulated [[Animatronics|animatronic]] band "sings" "[[One for My Baby (and One More for the Road)]]". Although the film's plot is set in England in the 1920s, this particular song did not exist until 1943, when [[Harold Arlen]] and [[Johnny Mercer]] wrote it as part of their film score for ''[[The Sky's the Limit (1943 film)|The Sky's the Limit]]''. [[Fred Astaire]] sang the [[jazz standard]] for the first time in that musical comedy. Likewise, the melody of the song "[[You Stepped Out of a Dream]]", written by [[Nacio Herb Brown]] (music) and [[Gus Kahn]] (lyrics) and first published in 1940, accompanies a scene depicting Dr. Phibes and Vulnavia dancing together in the ballroom of his mansion. Other musical anachronisms are Vulnavia's playing "[[Close Your Eyes (Bernice Petkere song)|Close Your Eyes]]" (1933) on the violin, or her placing in a car a music box that plays "[[Elmer's Tune]]" (1941). | ||

| Line 113: | Line 110: | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

* {{IMDb title}} | * {{IMDb title}} | ||

* {{AllMovie title}} | * {{AllMovie title}} | ||

| Line 120: | Line 117: | ||

* ''[https://collections-search.bfi.org.uk/web/Details/ChoiceFilmWorks/150047275 The Abominable Dr. Phibes]'' at the [[British Film Institute]] | * ''[https://collections-search.bfi.org.uk/web/Details/ChoiceFilmWorks/150047275 The Abominable Dr. Phibes]'' at the [[British Film Institute]] | ||

* {{TCMDb title}} | * {{TCMDb title}} | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Abominable Dr. Phibes, The}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Abominable Dr. Phibes, The}} | ||

Latest revision as of 21:02, 27 September 2024

| The Abominable Dr. Phibes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Robert Fuest |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Norman Warwick |

| Edited by | Tristam Cones |

| Music by | Basil Kirchin |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Anglo-EMI Film Distributors |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1.5 million[1] or $1,827,000[2] |

The Abominable Dr. Phibes is a 1971 British comedy horror film directed by Robert Fuest, written by James Whiton and William Goldstein,[3][4] and starring Vincent Price and Joseph Cotten.[5] Its Art Deco sets, dark humour, and performance by Price have made the film and its sequel Dr. Phibes Rises Again cult classics.[4] The film also features Hugh Griffith and Terry-Thomas, with an uncredited Caroline Munro appearing as Phibes's wife.

The film follows the title character, Dr Anton Phibes, who blames the medical team that attended to his wife's surgery four years earlier, for her death and sets out to exact vengeance on each one.[6] Phibes is inspired in his murder spree by the Ten Plagues of Egypt from the Old Testament,[7] although some plagues were dropped, new ones added and they are ordered differently from in the Bible.

Plot

Dr. Anton Phibes, a famous concert organist with doctorates in both music and theology, is believed to have been killed in a car crash in Switzerland in 1921, while racing home upon hearing of the death of his beloved wife, Victoria, during surgery. Phibes survived the crash, but was horribly scarred and left unable to speak. He remade his face with prosthetics and used his knowledge of acoustics to regain his voice. Resurfacing secretly in London in 1925, Phibes believes his wife was a victim of her doctors' incompetence, and begins elaborate plans to kill those he believes are responsible for her death.[8]

Aided in his quest for vengeance by his beautiful and silent assistant Vulnavia, Phibes uses the Ten Plagues of Egypt as his inspiration, wearing an amulet with Hebrew letters corresponding with each plague as he conducts the murders. After three doctors have been killed, Inspector Trout, a detective from Scotland Yard, learns that they all had worked under the direction of Dr Vesalius, who tells him the deceased had been on his team when treating Victoria, as were four other doctors and one nurse. Trout discovers one of Phibes's amulets (torn off during a struggle) at the murder scene of the fourth doctor, which takes place while he is interviewing Vesalius. He first takes it to the jeweller who made it, then to a rabbi to learn its meaning. Now believing Phibes may still be alive, Trout and Vesalius go to the Phibes mausoleum at Highgate Cemetery. Inside, they find a box of ashes in Phibes's coffin, but Trout deduces they are probably the remains of Phibes's chauffeur. Victoria's coffin is empty.

The police are unable to prevent Phibes from killing the remaining members of Vesalius's team, so they focus their efforts entirely on protecting Vesalius himself. Phibes kidnaps Vesalius's son Lem, then calls Vesalius and tells him to come alone to his mansion on Maldene Square if he wants to save his son's life. Trout refuses to let him go, so Vesalius knocks the inspector unconscious and races to Phibes's mansion, where he confronts him. Phibes tells him his son is under anaesthesia and prepared for surgery. Phibes has implanted a key near the boy's heart that will unlock his restraints. Vesalius has to surgically remove the key within six minutes (the same time Victoria was on the operating table) to release his son before acid from a container above Lem's head is released and kills him. Vesalius succeeds and moves the table out of the way. Vulnavia, who was ordered to destroy Phibes's mechanical creations, is surprised by Trout and his assistant; backing away, she is drenched with the acid and killed.

Convinced that he has accomplished his vendetta, Phibes retreats to the basement to inter himself in a stone sarcophagus containing the embalmed body of his wife. He proceeds to drain his blood while simultaneously replacing it with embalming fluid and lies down in the sarcophagus next to Victoria. The coffin's inlaid stone lid lowers into place, concealing it. Trout and the police arrive but cannot find Phibes. They recall that the "final curse" was darkness just before the basement goes dark.

Cast

- Vincent Price as Dr. Anton Phibes

- Joseph Cotten as Dr. Vesalius

- Hugh Griffith as the rabbi

- Terry-Thomas as Dr. Longstreet

- Peter Jeffrey as Inspector Harry Trout

- Derek Godfrey as Crow

- Norman Jones as Sgt. Tom Schenley

- John Cater as Superintendent Waverley

- Aubrey Woods as Goldsmith

- John Laurie as Darrow

- Maurice Kaufmann as Dr. Whitcombe

- Sean Bury as Lem Vesalius

- Susan Travers as Nurse Allen

- David Hutcheson as Dr. Hedgepath

- Edward Burnham as Dr. Dunwoody

- Alex Scott as Dr. Hargreaves

- Peter Gilmore as Dr. Kitaj

- Virginia North as Vulnavia

- Caroline Munro as Victoria Regina Phibes, Phibes's wife (uncredited)

Production

The film began as a script by writers James Whiton and William Goldstein. Studio American International Pictures purchased the script, seeing it as a good vehicle for their biggest star, Vincent Price.[9] Director Robert Fuest rewrote most of the script, altering Dr Phibes (who in the original script abused his assistant Vulnavia) to be more sympathetic. He also opted to add in some deliberate humour, since critics often razed Price for over-the-top performances, and changed the death of Dr Kitaj by rats to take place on a plane instead of on a boat. Fuest found the boat death implausible, questioning why Kitaj could not save himself by simply jumping into the water.[9] Peter Cushing was originally cast as Dr Vesalius, but bowed out due to the illness of his wife and was replaced by Joseph Cotten.[9] The film was shot on the "20s era" sets at Elstree Studios in Hertfordshire. The cemetery scenes were shot in Highgate Cemetery in London.[10][11] The exterior of Dr Phibes's mansion was Caldecote Towers at Immanuel College on Elstree Road.[11][12]

Music

The music that Phibes plays on the organ at the beginning of the film is "War March of the Priests" from Felix Mendelssohn's incidental music to Racine's play Athalie.

The film's incidental score was composed by Basil Kirchin and includes 1920s-era source music, most notably "Charmaine" and "Darktown Strutters' Ball".

One of several music-related errors or anachronisms within the film's storyline is the song overlaid as a recorded performance by one of the ostensibly mechanized musicians of "Dr. Phibes' Clockwork Wizards."[13] The pianist in this simulated animatronic band "sings" "One for My Baby (and One More for the Road)". Although the film's plot is set in England in the 1920s, this particular song did not exist until 1943, when Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer wrote it as part of their film score for The Sky's the Limit. Fred Astaire sang the jazz standard for the first time in that musical comedy. Likewise, the melody of the song "You Stepped Out of a Dream", written by Nacio Herb Brown (music) and Gus Kahn (lyrics) and first published in 1940, accompanies a scene depicting Dr. Phibes and Vulnavia dancing together in the ballroom of his mansion. Other musical anachronisms are Vulnavia's playing "Close Your Eyes" (1933) on the violin, or her placing in a car a music box that plays "Elmer's Tune" (1941).

A soundtrack LP was released concurrently with the film's appearance, which contained few selections from the score, but rather was composed mostly of character vocalizations by Paul Frees.[14][15] A proper soundtrack was released on CD in 2004 by Perseverance Records.

Critical reception

The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "This is Robert Fuest's second AIP feature... and his flat, unimaginative visual style dominates every frame. It is the same patchwork mixture of clumsy compositions and endless close-ups which jarred in Wuthering Heights, where it made genuine Bronté locations look like a cut-price studio. Here it transforms some obviously expensive art-deco sets into a messy accumulation of props and obliterates all sense of period without adding anything itself. The basically conventional script is not much more inspired, contriving to be coy and tongue-incheek without ever being witty, so that one positively longs for the days when horror (and API) took itself seriously. This crassness in dialogue and direction is all the more irritating in that aspects of Dr. Phibes suggest that it might have been a reasonably intriguing film: much of the Thirties gadgetry and apparatus is attractively designed, and the pairing of Vincent Price with Joseph Cotten could in the right circumstances have amounted to a stroke of genius. Here, both are effectively emasculated by their roles, with Cotten given little to do and Price in a virtually non-speaking part (for the purposes of the plot he has to be seen to speak through an electronic socket in his neck). Phibes' ten elaborate curses give rise to a few macabre moments, but the last is rather more disturbing in its suggestion that a sequel is already imminent."[16]

Howard Thompson of The New York Times wrote, "The plot, buried under all the iron tinsel, isn't bad. But the tone of steamroller camp flattens the fun."[17] Variety was generally positive, praising the "well-structured" screenplay, "outstanding" makeup for Vincent Price, and "excellent work" on the set designs.[18] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film three-and-a-half stars, calling it a "stylish, clever, shrieking winner", though he disliked "the lack of zip in the ending".[19] David Pirie of The Monthly Film Bulletin was negative, faulting director Robert Fuest's "flat, unimaginative visual style" and a script "contriving to be coy and tongue-in-cheek without ever being witty".[20]

In 2002, critic Christopher Null called the film "Vincent Price at his campy best ... A crazy script and an awesome score make this a true classic."[21]

In the early 2010s, Time Out London conducted a poll with several authors, directors, actors and critics who have worked within the horror genre to vote for their top horror films.[22] The Abominable Dr. Phibes placed at number 83 on their top 100 list.[23]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 88% based on 40 reviews, with an average rating of 7/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "The Abominable Dr. Phibes juggles horror and humor, but under the picture's campy façade, there's genuine pathos brought poignantly to life through Price's performance."[24] The film was not highly regarded by American International Pictures' home office until it became a box office success.[25]

Home video

MGM Home Entertainment released The Abominable Dr. Phibes on Region 1 DVD in 2001, followed by a tandem release with Dr. Phibes Rises Again in 2005. The film made its Blu-ray debut as part of Scream Factory's Vincent Price box set on 22 October 2013.[26][27]

A limited edition two-disc set, The Complete Dr. Phibes, was released in Region B Blu-ray on 16 June 2014 by Arrow Films.[28] Both films were later reissued separately by Arrow and as part of the nine-film/seven-disc Region B Blu-ray set The Vincent Price Collection on the Australian Shock label.[29]

The TV broadcast version of the film excises some of the more grisly scenes, such as a close-up of the nurse's locust-eaten corpse.

Sequel

A sequel, Dr. Phibes Rises Again, was released in 1972. It was also directed by Fuest and also stars Price as Phibes. Several other sequels were proposed, including The Bride of Dr. Phibes, but none were ever produced.[30]

References

- ^ Parish, James Robert; Whitney, Steven (1974). Vincent Price Unmasked. New York: Drake Publishers. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-87749-667-0.

- ^ Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American Film Distribution: The Changing Marketplace. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-8357-1776-2. Note: Figures are for distributor rentals in the United States and Canada.

- ^ "The Abominable Dr. Phibes". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ a b Weber, Eric. "The Abominable Dr. Phibes". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ "The Abominable Dr. Phibes". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 2012-07-12.

- ^ "The Abominable Doctor Phibes (1970)". British Horror Films. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ Firsching, Robert. "The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) – Robert Fuest | Review". AllMovie. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Rovin, Jeff (1987). The Encyclopedia of Super Villains. New York: Facts on File. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-8160-1356-2.

- ^ a b c Hallenbeck, Bruce G. (2009). Comedy-Horror Films: A Chronological History, 1914–2008. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-0-7864-5378-8.

- ^ "The Abominable Dr Phibes film locations". The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ a b Reeves, Tony (2006). The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations. Titan Books. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-1-84023-207-3.

- ^ Pykett, Derek (2008). British Horror Film Locations. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7864-3329-2.

- ^ "Dr. Phibes Clockwork Wizards" Archived 19 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Abominable Dr. Phibes, The – Soundtrack details". SoundtrackCollector. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ Lampley, Jonathan Malcolm (2010). Women in the Horror Films of Vincent Price. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-7864-3678-1.

- ^ "The Abominable Dr. Phibes". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 38 (444): 179. 1 January 1971 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (5 August 1971). "Price Is 'Abominable Dr. Phibes'". The New York Times. p. 25.

- ^ "The Abominable Doctor Phibes". Variety. 26 May 1971. p. 23.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (7 June 1971). "Dr. Phibes". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 16.

- ^ Pirie, David (September 1971). "The Abominable Dr. Phibes". The Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 38, no. 452. p. 179.

- ^ Null, Christopher (2002). "The Abominable Dr. Phibes". FilmCritic.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2008.

- ^ "The 100 best horror films". Time Out London. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ DC. "The 100 best horror films: the list". Time Out London. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ "The Abominable Dr. Phibes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ Smith, Gary A. (2009). The American International Pictures Video Guide. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-7864-3309-4.

- ^ James, Jonathan (26 April 2013). "Scream Factory Announces Vincent Price Blu-ray Collection, Including The Abominable Dr. Phibes and Witchfinder General". Daily Dead. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "The Vincent Price Collection". Shout! Factory. Archived from the original on 2 August 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ "The Complete Dr Phibes". Arrow Films. Archived from the original on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ McCarthy, J.H. "The Vincent Price Collection". Amazon. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ James, Jonathan (2012-12-01). "The Bride of Dr. Phibes Poster". Daily Dead. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

Bibliography

- Gerosa, Mario (2010). Robert Fuest e l'abominevole Dottor Phibes (in italiano). Alessandria, Italy: Edizioni Falsopiano. ISBN 978-88-89782-13-2.

- Humphreys, Justin (2018). The Dr. Phibes Companion. Albany, Georgia: BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-62933-293-2.

- Klemensen, Richard (October 2012). "The Definitive Dr. Phibes". Little Shoppe of Horrors. No. 29. Des Moines, Iowa.

External links

- The Abominable Dr. Phibes at IMDb

- The Abominable Dr. Phibes at AllMovieInvalid ID.

- The Abominable Dr. Phibes at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Abominable Dr. Phibes at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Abominable Dr. Phibes at the British Film Institute

- {{TCMDb title}} template missing ID and not present in Wikidata.

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with short description

- Template film date with 1 release date

- CS1 italiano-language sources (it)

- AllMovie titles with invalid value

- 1971 films

- 1971 black comedy films

- 1971 comedy horror films

- 1970s British films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s exploitation films

- 1970s serial killer films

- American International Pictures films

- British black comedy films

- British comedy horror films

- British exploitation films

- British films about revenge

- British serial killer films

- Fiction about prosthetics

- Films about the ten plagues of Egypt

- Films based on the Book of Exodus

- Films directed by Robert Fuest

- Films scored by Basil Kirchin

- Films set in 1921

- Films set in 1925

- Films set in London

- Films set in Switzerland

- Films shot at EMI-Elstree Studios

- Films shot in Hertfordshire

- Mad scientist films

- English-language comedy horror films

- English-language crime films