Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines: Difference between revisions

m (1 revision imported) |

No edit summary |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox film | {{Infobox film | ||

| name = Those Magnificent Men<br/>in their Flying Machines;<br/>Or, How I Flew from London to Paris<br/>in 25 Hours 11 Minutes | | name = Those Magnificent Men<br/>in their Flying Machines;<br/>Or, How I Flew from London to Paris<br/>in 25 Hours 11 Minutes | ||

| Line 113: | Line 110: | ||

=== Casting === | === Casting === | ||

[[Stuart Whitman]], the American lead, was selected over the first choice, [[Dick Van Dyke]], whose agents never contacted him about the offer.<ref name="DVD 12" /> [[Irina Demick]] was rumored to be romantically involved with Darryl F. Zanuck, who had campaigned for her casting.<ref name="DVD bonus2" /> | [[w:Stuart Whitman|Stuart Whitman]], the American lead, was selected over the first choice, [[w:Dick Van Dyke|Dick Van Dyke]], whose agents never contacted him about the offer.<ref name="DVD 12" /> [[Irina Demick|Irina Demick]] was rumored to be romantically involved with Darryl F. Zanuck, who had campaigned for her casting.<ref name="DVD bonus2" /> | ||

Character actor [[Michael Trubshawe]] and [[David Niven]] served together in the [[Highland Light Infantry]] during the Second World War; they made it a point to refer to uncredited characters in their films as "Trubshawe" or "Niven" as an inside joke.<ref name="DVD2" /> | Character actor [[Michael Trubshawe]] and [[David Niven]] served together in the [[w:Highland Light Infantry|Highland Light Infantry]] during the Second World War; they made it a point to refer to uncredited characters in their films as "Trubshawe" or "Niven" as an inside joke.<ref name="DVD2" /> | ||

Japanese actor [[Yūjirō Ishihara]] was [[Dubbing|dubbed]] due to his accent. Ishihara was dubbed by [[James Villiers]].<ref name="BFI: TMM">{{cite web |title=Cast: 'Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines or How I Flew From London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes' |url=http://ftvdb.bfi.org.uk/sift/title/54142?view=cast |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090115195744/http://ftvdb.bfi.org.uk/sift/title/54142?view=cast |archive-date=15 January 2009 |access-date=9 May 2013 |website=Film & TV Database |publisher=[[British Film Institute]]}}</ref> | Japanese actor [[w:Yūjirō Ishihara|Yūjirō Ishihara]] was [[w:Dubbing|dubbed]] due to his accent. Ishihara was dubbed by [[James Villiers]].<ref name="BFI: TMM">{{cite web |title=Cast: 'Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines or How I Flew From London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes' |url=http://ftvdb.bfi.org.uk/sift/title/54142?view=cast |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090115195744/http://ftvdb.bfi.org.uk/sift/title/54142?view=cast |archive-date=15 January 2009 |access-date=9 May 2013 |website=Film & TV Database |publisher=[[w:British Film Institute|British Film Institute]]}}</ref> | ||

===Locations=== | ===Locations=== | ||

| Line 144: | Line 141: | ||

The film includes reproductions of 1910-era aircraft, including a [[triplane]], [[monoplane]]s, [[biplane]]s and also [[Horatio Phillips]]'s 20-winged multiplane from 1904.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Evolution_of_Technology/phillips/Tech4.htm |title=Horatio Philipps and the Cambered Wing Design |website=The U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission |date=2003 |access-date=25 March 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100528011715/http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Evolution_of_Technology/phillips/Tech4.htm |archive-date=28 May 2010 }}</ref> Wheeler insisted on authentic materials but allowed the use of modern engines and modifications necessary to ensure safety. Of 20 types built in 1964 at £5,000 each, six could fly, flown by six stunt pilots and maintained by 14 mechanics.<ref name="DVD 1"/> The race take-off scene where seven aircraft are in the air at once included a composite addition of one aircraft. Flying conditions were monitored carefully, with aerial scenes filmed before 10 am or in early evening when the air was least turbulent, as the replicas, true to the originals, were flimsy, and control, especially in the lateral plane, tended to be marginal. When weather conditions were poor, interiors or other incidental sequences were shot instead. Wheeler eventually served not only as the technical adviser but also as the aerial supervisor throughout the production, and, later wrote a comprehensive background account of the film and the replicas that were constructed to portray period aircraft.<ref name="Wheeler (1965)">Wheeler (1965).</ref> | The film includes reproductions of 1910-era aircraft, including a [[triplane]], [[monoplane]]s, [[biplane]]s and also [[Horatio Phillips]]'s 20-winged multiplane from 1904.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Evolution_of_Technology/phillips/Tech4.htm |title=Horatio Philipps and the Cambered Wing Design |website=The U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission |date=2003 |access-date=25 March 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100528011715/http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Evolution_of_Technology/phillips/Tech4.htm |archive-date=28 May 2010 }}</ref> Wheeler insisted on authentic materials but allowed the use of modern engines and modifications necessary to ensure safety. Of 20 types built in 1964 at £5,000 each, six could fly, flown by six stunt pilots and maintained by 14 mechanics.<ref name="DVD 1"/> The race take-off scene where seven aircraft are in the air at once included a composite addition of one aircraft. Flying conditions were monitored carefully, with aerial scenes filmed before 10 am or in early evening when the air was least turbulent, as the replicas, true to the originals, were flimsy, and control, especially in the lateral plane, tended to be marginal. When weather conditions were poor, interiors or other incidental sequences were shot instead. Wheeler eventually served not only as the technical adviser but also as the aerial supervisor throughout the production, and, later wrote a comprehensive background account of the film and the replicas that were constructed to portray period aircraft.<ref name="Wheeler (1965)">Wheeler (1965).</ref> | ||

The following competitors were listed: | The following competitors were listed: | ||

# Richard Mays: [[Antoinette IV]] (Aircraft number 8: flying replica) | # Richard Mays: [[Antoinette IV]] (Aircraft number 8: flying replica) | ||

# Sir Percy Ware-Armitage: [[Roe IV Triplane|Avro Triplane IV]] (Aircraft number 12: flying replica) | # Sir Percy Ware-Armitage: [[Roe IV Triplane|Avro Triplane IV]] (Aircraft number 12: flying replica) | ||

| Line 167: | Line 164: | ||

The Eardley Billing Tractor Biplane replica flown by David Watson appeared in two guises, in more or less authentic form, impersonating an early German tractor biplane, and also as the Japanese pilot's mount, modified with boxkite-like side curtains over the [[interplane strut]]s, a covered fuselage, and colourful "oriental" decorations.<ref>Carlson (2012), p. 328.</ref> | The Eardley Billing Tractor Biplane replica flown by David Watson appeared in two guises, in more or less authentic form, impersonating an early German tractor biplane, and also as the Japanese pilot's mount, modified with boxkite-like side curtains over the [[interplane strut]]s, a covered fuselage, and colourful "oriental" decorations.<ref>Carlson (2012), p. 328.</ref> | ||

[[File:Alberto Santos Dumont flying the Demoiselle (1909).jpg| | [[File:Alberto Santos Dumont flying the Demoiselle (1909).jpg|right|thumb|250px|[[Alberto Santos-Dumont|Santos-Dumont]] flying his Demoiselle in Paris, 1907]] | ||

In addition to the flying aircraft, several unsuccessful aircraft of the period were represented by non-flying replicas{{spaced ndash}}including contraptions such as an [[ornithopter]] (the Passat Ornithopter) flown by the Italian contender, the Walton Edwards Rhomboidal, Picat Dubreuil, Philips Multiplane and the Little Fiddler (a canard, or tail-first design). Several of the "non-flying" types flew with the help of "movie magic". The Lee Richards Annular Biplane with circular wings (built by Denton Partners on [[Woodley Aerodrome]], near Reading) was "flown on wires" during the filming.<ref name="Wheeler (1965) Lee Richards">Wheeler (1965), pp. 92-93</ref> | In addition to the flying aircraft, several unsuccessful aircraft of the period were represented by non-flying replicas{{spaced ndash}}including contraptions such as an [[ornithopter]] (the Passat Ornithopter) flown by the Italian contender, the Walton Edwards Rhomboidal, Picat Dubreuil, Philips Multiplane and the Little Fiddler (a canard, or tail-first design). Several of the "non-flying" types flew with the help of "movie magic". The Lee Richards Annular Biplane with circular wings (built by Denton Partners on [[Woodley Aerodrome]], near Reading) was "flown on wires" during the filming.<ref name="Wheeler (1965) Lee Richards">Wheeler (1965), pp. 92-93</ref> | ||

| Line 177: | Line 174: | ||

[[Peter Hillwood]] of Hampshire Aero Club constructed an [[Roe IV Triplane|Avro Triplane Mk IV]], using drawings provided by Geoffrey Verdon Roe, son of [[Alliott Verdon Roe|A.V. Roe]], the designer. The construction of the triplane followed A.V. Roe's specifications and was the only replica that utilised wing-warping successfully. With a more powerful 90 hp Cirrus II replacing the 35 hp Green engine that was in the original design, the Avro Triplane proved to be a lively performer even with a stuntman dangling from the fuselage.<ref name="DVD bonus"/> | [[Peter Hillwood]] of Hampshire Aero Club constructed an [[Roe IV Triplane|Avro Triplane Mk IV]], using drawings provided by Geoffrey Verdon Roe, son of [[Alliott Verdon Roe|A.V. Roe]], the designer. The construction of the triplane followed A.V. Roe's specifications and was the only replica that utilised wing-warping successfully. With a more powerful 90 hp Cirrus II replacing the 35 hp Green engine that was in the original design, the Avro Triplane proved to be a lively performer even with a stuntman dangling from the fuselage.<ref name="DVD bonus"/> | ||

[[File:Antoinette V.jpg|thumb| | [[File:Antoinette V.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Original [[Daguerreotype]] of an Antoinette IV c. 1910{{spaced ndash}}note triangular ailerons hinged on trailing edge of wing]] | ||

The [[Antoinette IV]] film model closely replicated the slim, graceful monoplane that was very nearly the first aircraft to fly the [[English Channel]], in the hands of [[Hubert Latham]], and won several prizes in early competitions. When the Hants and Sussex Aviation Company from Portsmouth Aerodrome undertook its construction, the company followed the original structural specifications carefully, although an out-of-period [[de Havilland|de Havilland Gypsy]] I engine was used. The Antoinette's wing structure proved, however, to be dangerously flexible, and lateral control was very poor, even after the wing bracing was reinforced with extra wires, and the original wing-warping was replaced with ailerons (hinged on the rear spar rather than from the trailing edge, as in the original Antoinette). Nonetheless, even in its final configuration the Antoinette was marginal in terms of stability and lateral control and great care had to be taken during its flying sequences, most flights being straight "hops".<ref name="Wheeler (1965) Antoinette">Wheeler (1965), pp. 27-35</ref> | The [[Antoinette IV]] film model closely replicated the slim, graceful monoplane that was very nearly the first aircraft to fly the [[English Channel]], in the hands of [[Hubert Latham]], and won several prizes in early competitions. When the Hants and Sussex Aviation Company from Portsmouth Aerodrome undertook its construction, the company followed the original structural specifications carefully, although an out-of-period [[de Havilland|de Havilland Gypsy]] I engine was used. The Antoinette's wing structure proved, however, to be dangerously flexible, and lateral control was very poor, even after the wing bracing was reinforced with extra wires, and the original wing-warping was replaced with ailerons (hinged on the rear spar rather than from the trailing edge, as in the original Antoinette). Nonetheless, even in its final configuration the Antoinette was marginal in terms of stability and lateral control and great care had to be taken during its flying sequences, most flights being straight "hops".<ref name="Wheeler (1965) Antoinette">Wheeler (1965), pp. 27-35</ref> | ||

| Line 223: | Line 220: | ||

| [[Golden Globes]] || Most Promising Newcomer{{spaced ndash}}Male || James Fox || {{nom}} | | [[Golden Globes]] || Most Promising Newcomer{{spaced ndash}}Male || James Fox || {{nom}} | ||

|} | |} | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 264: | Line 257: | ||

* {{AllMovie title| 49617 }} | * {{AllMovie title| 49617 }} | ||

* {{Rotten Tomatoes| those_magnificent_men_in_their_flying_machines }} | * {{Rotten Tomatoes| those_magnificent_men_in_their_flying_machines }} | ||

[[Category:1960s adventure comedy films]] | [[Category:1960s adventure comedy films]] | ||

| Line 283: | Line 274: | ||

[[Category:1960s English-language films]] | [[Category:1960s English-language films]] | ||

[[Category:1960s British films]] | [[Category:1960s British films]] | ||

[[Category:British comedy films]] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:57, 13 March 2023

| Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines; Or, How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes | |

|---|---|

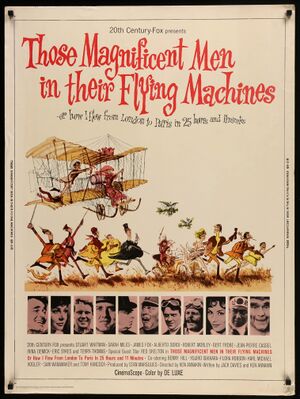

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Annakin |

| Written by | Ken Annakin Jack Davies |

| Produced by | Stan Margulies |

| Starring | Stuart Whitman Sarah Miles Terry Thomas Robert Morley James Fox |

| Cinematography | Christopher Challis |

| Edited by | Gordon Stone Anne V. Coates |

| Music by | Ron Goodwin |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 138 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom[1] |

| Languages | English Italian German French |

| Budget | $6.5 million[3] |

| Box office | $31 million[4] |

Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines; Or, How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 Hours and 11 Minutes is a 1965 British period comedy film that satirizes the early years of aviation. Directed and co-written by Ken Annakin, the film stars an international ensemble cast, including Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, Robert Morley, Terry-Thomas, James Fox, Red Skelton, Benny Hill, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Gert Fröbe and Alberto Sordi.

Based on a screenplay entitled Flying Crazy, the fictional account is set in 1910, when English press magnate Lord Rawnsley offers £10,000 (equivalent to £1,290,000 in 2023[5]) to the winner of the Daily Post air race from London to Paris to prove that Britain is "number one in the air".[6]

Plot

A brief narration outlines man's first attempts to fly since the Stone Age inspired by a bird's flight, seen with footage from the silent film era, and man being represented by a "test pilot" (Red Skelton) encountering periodic misfortune in his attempts.

In 1910, just seven years after the first heavier-than-air flight, aircraft are fragile and unreliable contraptions, piloted by "intrepid birdmen". Pompous British newspaper magnate Lord Rawnsley (Robert Morley) forbids his would-be aviatrix daughter, ardent suffragette Patricia (Sarah Miles), to fly. Aviator Richard Mays (James Fox), a young army officer and (at least in his own eyes) Patricia's fiancé, conceives the idea of an air race from London to Paris to advance the cause of British aviation and his career. With Patricia's support, he persuades Lord Rawnsley to sponsor the race as a publicity stunt for his newspaper.

Rawnsley, who takes full credit for the idea, announces the event to the press, and invitations are sent to leading aviators all over the world. Dozens of participants arrive at the airfield at the "Brookley" Motor Racing Track, where the fliers make practice runs in the days prior to the race. During this time, a wildly mixed international assembly of aviators begins rubbing shoulders with each other, most of them conforming to national stereotypes: The by-the-book Prussian officer Colonel Manfred von Holstein (Gert Fröbe), who becomes the victim of Frenchman Pierre Dubois' (Jean-Pierre Cassel) various pranks; the impetuous Italian Count Emilio Ponticelli (Alberto Sordi), who buys various aircraft from designer Harry Popperwell (Tony Hancock) and wrecks them in test flights; the unscrupulous British baronet Sir Percy Ware-Armitage (Terry-Thomas), aided by his bullied servant, Courtney (Eric Sykes); and the rugged American cowboy Orvil Newton (Stuart Whitman) who falls for Patricia, forming a love triangle with her and Mays.

As the teams test their aircraft in the days before the race, Newton gets caught in the rigging of Sir Percy's plane, which crashes in the nearby sewage farm. Newton later stops the German's aircraft after its tail breaks off and runs out of control. This leads to Patricia falling for him even more and Mays to become more jealous. At a celebration in Brighton, Mays confronts Newton, sparking a fierce rivalry between them for Patricia's hand, just before Japan's official contestant, naval officer Yamamoto, arrives at the airfield.

As Yamamoto is officially greeted, Patricia convinces Newton to take her flying and they race back to the airfield, followed by Mays and her father, who are intent on stopping them. Not long after taking off, one of the struts on Newton's plane breaks, and Patricia has to fly the plane while Newton repairs it with his belt. When Newton lands, Lord Rawnsley throws him out of the race. Patricia apologizes to Newton, and Rawnsley gives in after she threatens to start an international incident. Meanwhile, Holstein, insulted by the French team's mockery, challenges Dubois to a duel. Dubois agrees, and opts for gas balloons and blunderbusses as his weapons of choice. Both balloons and their pilots end up in the filthy waters of the adjacent sewage farm.

At the party the night before the race, Sir Percy sabotages Yamamoto and Newton's planes, and Rumpelstoss, the German pilot, is incapacitated by a laxative meant for Yamamoto. As the competitors take off the next day, with Holstein standing in for Rumpelstoss, Yamamoto's aircraft crashes and he remains pinned in the wreck as a fireman is hesitant to give him a knife to cut himself free due to fears that he will commit seppuku. Fuel blockages and other technical mishaps additionally hamper the fliers, until most of them safely arrive at Dover, their checkpoint before the final flight across the English Channel.

That night, Sir Percy cheats by having his aircraft taken across by boat, but is delayed by excited locals when he arrives. The other contestants fly across the Channel in the morning, but Holstein, unfortunately, looses his manual and falls into the sea. Sir Percy gets his comeuppance when he becomes disoriented by the smoke from a locomotive between Calais and Paris, causing him to jam his landing gear between two of the train cars. As he runs along the top trying to get the driver's attention, the train passes through a tunnel, wrecking his aircraft.

Coming into Paris, Ponticelli's plane catches fire, and Newton detours to rescue him as Mays is landing, winning for Britain. Mays recognises Newton's heroism and shares the glory and the prize with him, while Ponticelli agrees to give up flying for his family. The only other successful aviator is Dubois, completing his race for France. Patricia finally chooses Newton, breaking the love triangle. Their kiss is interrupted by a strange noise: they and the others at the field look up to see a flyover by six English Electric Lightning jet fighters, as the time period leaps forward to the "present" (1965).

Outlined are the still-persisting hazards of modern flying despite today's advanced technology, as a night-time civilian flight across the English Channel is cancelled owing to heavy fog. One of the delayed passengers (Skelton) gets the idea of learning to fly under his own power, perpetuating man's pioneering spirit.

Cast

- Stuart Whitman as Orvil Newton

- Sarah Miles as Patricia Rawnsley

- James Fox as Richard Mays

- Alberto Sordi as Count Emilio Ponticelli

- Robert Morley as Lord Rawnsley

- Gert Fröbe as Colonel Manfred von Holstein

- Jean-Pierre Cassel as Pierre Dubois

- Irina Demick as Brigitte/Ingrid/Marlene/Françoise/Yvette/Betty

- Red Skelton as Neanderthal Man, Roman birdman, Middle Ages inventor, Victorian-era pilot, Rocket pack inventor, Modern airline passenger

- Terry-Thomas as Sir Percy Ware-Armitage

- Eric Sykes as Courtney

- Benny Hill as Fire Chief Perkins

- Yūjirō Ishihara as Yamamoto

- Dame Flora Robson as Mother Superior

- Karl Michael Vogler as Captain Rumpelstoss

- Sam Wanamaker as George Gruber

- Tony Hancock as Harry Popperwell

- Eric Barker as French Postman

- Maurice Denham as Trawler Skipper

- Fred Emney as Colonel

- Gordon Jackson as MacDougal

- Davy Kaye as Jean, Chief mechanic for Pierre Dubois

- John Le Mesurier as French Painter

- Jeremy Lloyd as Lieutenant Parsons

- Zena Marshall as Countess Sophia Ponticelli

- Millicent Martin as Air Hostess

- Eric Pohlmann as Italian Mayor

- Marjorie Rhodes as Waitress

- Norman Rossington as Assistant Fire Chief

- Willie Rushton as Tremayne Gascoyne

- Graham Stark as Fireman

- Jimmy Thompson as Photographer

- Michael Trubshawe as Niven, Lord Rawnsley's aide

- Cicely Courtneidge as Colonel's Wife

- Ronnie Stevens as Reporter

- Ferdy Mayne as French Official

- Vernon Dobtcheff as French Team Member

- James Robertson Justice as the voice of the narrator

Production

Origins

Director Ken Annakin had been interested in aviation from his early years when pioneering aviator, Sir Alan Cobham took him up in a flight in a biplane. Later in the Second World War, Annakin had served in the RAF when he had begun his career in film documentaries. In 1963, with co-writer Jack Davies, Annakin had been working on an adventure film about transatlantic flights when the producer's bankruptcy aborted the production. Fresh from his role as director of the British exterior segments in The Longest Day (1962), Annakin suggested an event from early aviation to Darryl F. Zanuck, his producer on The Longest Day.[7][Note 1]

Zanuck financed an epic faithful to the era, with a £100,000 stake, deciding on the name, Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines after Elmo Williams, managing director of 20th Century Fox in Europe, told him his wife Lorraine Williams had written an opening for a song that Annakin complained would "seal the fate of the movie":

Those magnificent men in their flying machines,

They go up, Tiddley up, up,

They go down, Tiddley down, down.[9]

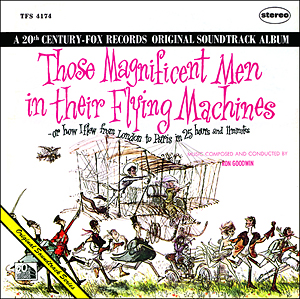

After being put to music by Ron Goodwin, the "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines" song was released as a single in 1965 on the Stateside label (SS 422), together with an accompanying soundtrack album (SL 10136).[10]

An international cast plays the array of contestants with the film opening with a brief, comic prologue on the history of flight, narrated by James Robertson Justice and featuring American comedian Red Skelton.[11] In a series of silent blackout vignettes that incorporate stock footage of unsuccessful attempts at early aircraft, Skelton depicted a recurring character whose adventures span the centuries. The early aviation history sequence that begins the film is followed by a whimsical animated opening credit sequence drawn by caricaturist Ronald Searle, accompanied by the title song.[12]

Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines ... concludes with an epilogue in a fogbound 1960s London airport when cancellation of flights to Paris is announced. The narrator remarks that today a jet makes the trip in seven minutes, but "it can take longer". One frustrated passenger (Skelton, again) starts wing-flapping motions with his arms, and the scene morphs into the animation from the title sequence for the closing credits. This was Skelton's final feature film appearance; he was in Europe filming the 1964–65 season of his television series, The Red Skelton Show.[12]

One of the features of the film was British and international character actors who enlivened the foibles of each contestant's nationality. The entertainment comes from the dialogue and characterisations and the aerial stunts, with heroism and gentlemanly conduct. British comedy actors of the day, Benny Hill, Eric Sykes, Terry-Thomas and Tony Hancock, among others, provided madcap misadventures.[13] While Terry-Thomas had a substantial leading role as a "bounder", Hill, Sykes and Hancock played lesser cameos.[14] Although Hancock had broken his leg off-set, two days into filming, Annakin wrote his infirmity into the story, and his leg bound in a cast figured in a number of scenes.[8]

In a recurring gag suggested by Zanuck, Irina Demick plays a series of flirts who are all pursued by the French pilot. First, she is Brigitte (French), then Ingrid (Swedish), Marlene (German), Françoise (Belgian), Yvette (Bulgarian), and finally, Betty (British).[12]

Another aspect was the fluid writing and directing with Annakin and Davies feeding off each other. They had worked together on Very Important Person (1961), The Fast Lady (1962) and Crooks Anonymous (1962). Annakin and Davies continued to develop the script with zany interpretations. When the German character played by Gert Fröbe contemplates piloting his country's entry, he climbs into the cockpit and retrieves a manual. Annakin and Davies devised a quip on the spot, having him read out: "No. 1. Sit down."[15] Although a comedy, elements of Annakin's documentary background were evident with authentic sets, props and costumes. More than 2,000 extras out in authentic costumes were in the climactic race launch which was combined with entrants in the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run being invited on set as part of their 1964 annual run, an unexpected coup in gaining numerous period vehicles to dress the set.[8]

A troublesome on-set distraction occurred when the two lead actors, Stuart Whitman and Sarah Miles, fell out early in the production.[16] Director Ken Annakin commented that it began with an ill-timed pass by Whitman. (Whitman was married at the time, although he would divorce in 1966.) Miles "hated his guts" and rarely deigned to speak to him afterward unless the interaction was required by the script.[7] Annakin employed a variety of manipulations to ensure the production still proceeded smoothly. The stars made peace with each other after on-set filming concluded; their interactions were civil during final re-takes of scenes and voice-overs.[8]

The film played in cinemas as the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union hit a new gear. For its first audiences the film's depiction of an international flight competition taking place in an earlier, lower-tech era offered a fun-house mirror reflection of contemporary adventures by Space Age pioneers.

Casting

Stuart Whitman, the American lead, was selected over the first choice, Dick Van Dyke, whose agents never contacted him about the offer.[17] Irina Demick was rumored to be romantically involved with Darryl F. Zanuck, who had campaigned for her casting.[18]

Character actor Michael Trubshawe and David Niven served together in the Highland Light Infantry during the Second World War; they made it a point to refer to uncredited characters in their films as "Trubshawe" or "Niven" as an inside joke.[19]

Japanese actor Yūjirō Ishihara was dubbed due to his accent. Ishihara was dubbed by James Villiers.[20]

Locations

The film used period accurate, life-size working aeroplane models and replicas to create an early 20th century airfield, the 'Brookley Motor Racing Track' (fashioned after Brooklands where early automotive racing and aviators shared the facilities for testing).[21] All Brookley's associated trappings of structures, aircraft and vehicles (including a rare 1907 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost, subsequently estimated to be worth 50 million dollars)[8] were part of the exterior set at Booker Airfield, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, England.[7]

The completed set featured a windmill as a lookout tower as well as serving as a restaurant (the "Old Mill Cafe"). A circular, banked track was also built and featured in a runaway motorcycle sequence in the film. In addition, the field adjacent to the windmill was used as the location for a number of aerial close-up shots of the pilots. Hangars were constructed in rows, bearing the names of real and fictional manufacturers: A.V. Roe & Co., Bristol: The British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, Humber, three Sopwith hangars, Vickers and Ware-Armitage Manufacturing Co (a British in-joke, as Armitage Ware was the UK's largest manufacturer of toilets and urinals). A grandstand was added for spectators.[7]

When the production was unable to obtain rights to film main sequences over Paris, models of the aircraft and a miniature Parisian set played a prominent role in sequences depicting Paris. A mock-up of Calais was also constructed.[22] Interior and studio sets at Pinewood Studios were used for bluescreen and special effects while exterior and interior footage of Rawnsley's Manor House were shot at Pinewood Studios in Iver Heath, Buckinghamshire. Other principal photography used location shooting in Kent at Dover Castle, along with The White Cliffs of Dover and Dover beach.[23] In the scene where the aircraft start near Dover to pursue the race, modern ferries were visible in one harbour.

The location where Sir Percy's aircraft lands on a train is the now closed line from Bedford to Hitchin. The tunnel into which they fly is the Old Warden Tunnel near the village of the same name in Bedfordshire; the tunnel had only recently been closed, and in the panning shot through the railway cutting, the cooling towers of the now-demolished Goldington power station can be seen. The locomotive is former Highland Railway Jones Goods Class No 103. About 1910, French Railways built duplicates of a Highland Railway Class "The Castles" which were a passenger version of the Jones Goods.[24]

The Royal Air Force base at the village of Henlow, RAF Henlow, was another Bedfordshire location used for filming.[25]

The opening shot of the film is of The Long Walk leading to Windsor Castle filmed in Windsor, Berkshire, England.

Don Sharp shot second unit with flying and stunts.[26][27]

Principal photography

The film was photographed in 65 mm Todd-AO (which produces a 70 mm print once the sound tracks are added) by Christopher Challis. The head technical consultant during planning was Air Commodore Allen H. Wheeler from the Royal Air Force. Wheeler had previously restored a 1910-era Blériot with his son, and provided invaluable assistance in the restoration and recreation of period aircraft for the film.

The camera platforms included a modified Citroën sedan, camera trucks, helicopters and a flying rig constructed by Dick Parker. Parker had built it for model sequences in Strategic Air Command (1955). The rig consisted of two construction cranes and a hydraulically operated device to tilt and position a model, along with 200 ft (61 m) of cables. Parker's rig allowed actors to sit inside full-scale models suspended 50 ft (15 m) above the ground, yet provide safety and realism for staged flying sequences, with the sky realistically in the background. A further hydraulic platform did away with matte shots of aircraft in flight. The platform was large enough to mount an aircraft and Parker or stunt pilots could manipulate its controls for realistic bluescreen sequences. Composite photography was used when scenes called for difficult shots; these were completed at Pinewood Studios. Some shots were created with rudimentary cockpits and noses grafted to an Alouette helicopter. One scene over Paris was staged with small models when Paris refused an overflight. However, for the majority of flying scenes, full-scale flying aircraft were employed.[8]

Aircraft

The film includes reproductions of 1910-era aircraft, including a triplane, monoplanes, biplanes and also Horatio Phillips's 20-winged multiplane from 1904.[28] Wheeler insisted on authentic materials but allowed the use of modern engines and modifications necessary to ensure safety. Of 20 types built in 1964 at £5,000 each, six could fly, flown by six stunt pilots and maintained by 14 mechanics.[7] The race take-off scene where seven aircraft are in the air at once included a composite addition of one aircraft. Flying conditions were monitored carefully, with aerial scenes filmed before 10 am or in early evening when the air was least turbulent, as the replicas, true to the originals, were flimsy, and control, especially in the lateral plane, tended to be marginal. When weather conditions were poor, interiors or other incidental sequences were shot instead. Wheeler eventually served not only as the technical adviser but also as the aerial supervisor throughout the production, and, later wrote a comprehensive background account of the film and the replicas that were constructed to portray period aircraft.[29]

The following competitors were listed:

- Richard Mays: Antoinette IV (Aircraft number 8: flying replica)

- Sir Percy Ware-Armitage: Avro Triplane IV (Aircraft number 12: flying replica)

- Orvil Newton: Bristol Boxkite, nicknamed "The Phoenix Flyer" and inaccurately referred to as a Curtiss (Aircraft number 7: flying replica)

- Lieutenant Parsons: Picat Dubreuil nicknamed "HMS Victory" (Aircraft number 4)

- Harry Popperwell: Dixon Nipper "Little Fiddler" (Aircraft number 5)

- Colonel Manfred von Holstein and Captain Rumpelstoss: Eardley Billing Tractor Biplane (Aircraft number 11: flying replica)

- Mr Wallace: Edwards Rhomboidal (Aircraft number 14)

- Charles Wade: (Aircraft number unknown)

- Mr Yamamoto: Japanese Eardley Billing Tractor Biplane (Aircraft number 1: duplicate flying replica)

- Count Emilio Ponticelli: Philips Multiplane, Passat Ornithopter, Lee-Richards Annular Biplane and Vickers 22 Monoplane (Aircraft number 2: flying replica)

- Henri Monteux: (Aircraft number unknown)

- Pierre Dubois: Santos-Dumont Demoiselle (Aircraft number 9: flying replica)

- Mr Mac Dougall: Blackburn Monoplane nicknamed "Wake up Scotland" (Aircraft number 6: original vintage aircraft)

- Harry Walton (no number assigned).

While each aircraft was an accurate reproduction, some "impersonated" other types. For instance, The Phoenix Flyer was a Bristol Boxkite built by F.G. Miles Engineering Co. at Ford, Sussex, representing a Curtiss biplane of 1910 vintage. Annakin had apparently expressed a desire to have a Wright Flyer in the film.[22] The Bristol (a British derivative of the French 1909 Farman biplane) was chosen instead, because it shared a common general layout with a Wright or Curtiss pusher biplane of the era, and had an excellent reputation for tractability.[30] For the impersonation, the replica had "The Phoenix Flyer" painted on its outer rudder surfaces and was also called a "Gruber-Newton Flyer" adding the name of its primary backer to the nomenclature; although the American pilot character, Orvil Newton inaccurately describes his aircraft to Patricia Rawnsley as a "Curtiss with an Anzani engine."[8]

F. G. Miles, chiefly responsible for its design and manufacture, built the replica Bristol Boxkite with the original standard twin rudder installation and powered the replica with a Rolls-Royce-manufactured version of the 65 hp Continental A65. In the course of testing, Wheeler had a third rudder inserted between the other two (some original Boxkites also had this fitting) to improve directional control, and substituted a more powerful 90 hp Rolls-Royce C90 that still barely delivered the power of the original 50 hp Gnome rotary at the power settings used for the Boxkite. The replica achieved a 45 mph top speed.[31] The Boxkite was tractable, however, and the scene in the film when the aircraft loses a pair of main wheels just after take off but lands smoothly, was repeated 20 times for the cameras. In the penultimate flying scene, a stuntman was carried in the Boxkite's undercarriage and carried out a fall and roll (the stunt had to be repeated to match the principal actor's roll and revival). Slapstick stunts on the ground and in the air were a major element and often the directors requested repeated stunts; the stuntmen were more than accommodating; it meant more pay.[22]

The Eardley Billing Tractor Biplane replica flown by David Watson appeared in two guises, in more or less authentic form, impersonating an early German tractor biplane, and also as the Japanese pilot's mount, modified with boxkite-like side curtains over the interplane struts, a covered fuselage, and colourful "oriental" decorations.[32]

In addition to the flying aircraft, several unsuccessful aircraft of the period were represented by non-flying replicas – including contraptions such as an ornithopter (the Passat Ornithopter) flown by the Italian contender, the Walton Edwards Rhomboidal, Picat Dubreuil, Philips Multiplane and the Little Fiddler (a canard, or tail-first design). Several of the "non-flying" types flew with the help of "movie magic". The Lee Richards Annular Biplane with circular wings (built by Denton Partners on Woodley Aerodrome, near Reading) was "flown on wires" during the filming.[33]

The flying replicas were specifically chosen to be different enough that an ordinary audience member could distinguish them. They were all types reputed to have flown well, in or about 1910. In most cases this worked well, but there were a few surprises, adding to an accurate historical reassessment of the aircraft concerned. For example, in its early form, the replica of the Santos-Dumont Demoiselle, a forerunner of today's ultralight aircraft, was unable to leave the ground except in short hops. Extending the wingspan and fitting a more powerful Ardem 50 hp engine produced only marginal improvement. When Doug Bianchi and the Personal Planes production staff who constructed the replica consulted with Allen Wheeler, he recalled that the Demoiselle's designer and first pilot, Alberto Santos-Dumont was a very short, slightly built man. A suitably small pilot, Joan Hughes, a wartime member of the Air Transport Auxiliary who was the Airways Flying Club chief instructor, was hired. With the reduced payload, the diminutive Demoiselle flew very well, and Hughes proved a consummate stunt flyer, able to undertake exacting manoeuvres.[7]

In 1960, Bianchi had created a one-off Vickers 22 (Blériot type) Monoplane, using Vickers Company drawings intended for the Vickers Flying Club in 1910. 20th Century Fox purchased the completed replica although it required a new engine and modifications including replacing the wooden fuselage structure with welded steel tubing as well as incorporating ailerons instead of wing-warping. The Vickers 22 became the final type used by the Italian contestant.[34] Sometime after the film wrapped, the Vickers was sold to a buyer in New Zealand. It is believed to have flown once, at Wellington Airport in the hands of Keith Trillo, a test pilot involved in a number of aircraft certification programmes, and is now at the Southward Car Museum, Otaihanga, New Zealand.[35]

Peter Hillwood of Hampshire Aero Club constructed an Avro Triplane Mk IV, using drawings provided by Geoffrey Verdon Roe, son of A.V. Roe, the designer. The construction of the triplane followed A.V. Roe's specifications and was the only replica that utilised wing-warping successfully. With a more powerful 90 hp Cirrus II replacing the 35 hp Green engine that was in the original design, the Avro Triplane proved to be a lively performer even with a stuntman dangling from the fuselage.[22]

The Antoinette IV film model closely replicated the slim, graceful monoplane that was very nearly the first aircraft to fly the English Channel, in the hands of Hubert Latham, and won several prizes in early competitions. When the Hants and Sussex Aviation Company from Portsmouth Aerodrome undertook its construction, the company followed the original structural specifications carefully, although an out-of-period de Havilland Gypsy I engine was used. The Antoinette's wing structure proved, however, to be dangerously flexible, and lateral control was very poor, even after the wing bracing was reinforced with extra wires, and the original wing-warping was replaced with ailerons (hinged on the rear spar rather than from the trailing edge, as in the original Antoinette). Nonetheless, even in its final configuration the Antoinette was marginal in terms of stability and lateral control and great care had to be taken during its flying sequences, most flights being straight "hops".[36]

The realism and the attention to detail in the replicas of vintage machines are a major contributor to the enjoyment of the film, and although a few of the "flying" stunts were achieved through the use of models and cleverly disguised wires, most aerial scenes featured actual flying aircraft. The few genuine vintage aircraft used included a Deperdussin used as set dressing, and the flyable 1912 Blackburn Monoplane "D" (the oldest genuine British aircraft still flying[37]), belonged to the Shuttleworth Trust based at Old Warden, Bedfordshire. When the filming was completed, the "1910 Bristol Boxkite" and the "1911 Roe IV Triplane" were retained in the Shuttleworth Collection,[38] Both replicas are still in flyable condition, albeit flying with different engines.[39] For his role in promoting the film, the non-flying "Passat Ornithopter" was given to aircraft restorer and preservationist, Cole Palen who displayed it at his Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, New York, where it is still on display.[40]

Despite the reliance on flying stunts and their inherent danger, the one near-tragedy occurred on the ground when a stunt went wrong. Stuntman Ken Buckle inadvertently turned the throttle to full on a runaway motorbike and sidecar, launching himself through the retaining wall on the sloped Brookley racing track and crashing into the adjoining cesspool, off-camera. Thinking quickly, the special effects man on the other side of the wall saw the motorbike hurtling towards him and set off the accompanying explosion, creating a realistic waterspout. Lucky to escape with only facial bruises and a dislocated collarbone, as he struggled to his feet, Buckle apologised for having messed up, but the shot "was in the can".[8]

During the promotional junkets accompanying the film in 1965, a number of the vintage aircraft and film replicas used in the production were flown in both the United Kingdom and the United States. The pilots who had been part of the aerial team readily agreed to accompany the promotional tour to have a chance to fly these aircraft again.[22]

Reception

Critical

Those Magnificent Men In their Flying Machines ... had its Royal World Premiere on 3 June 1965 at the Astoria Theatre in the West End of London in the presence of H.R.H. The Duke of Edinburgh. Contemporary reviews judged Those Magnificent Men In their Flying Machines ... as "good fun." In The New York Times, Bosley Crowther thought it "a funny picture, highly colorful, and it does move".[41] Variety felt similarly: "As fanciful and nostalgic a piece of clever picture-making as has hit the screen in recent years, this backward look into the pioneer days of aviation, when most planes were built with spit and bailing wire, is a warming entertainment experience."[42] When the film turned up on television for the first time in 1969, TV Guide summed up most critical reviews: "Good, clean fun, with fast and furious action, good cinematography, crisp dialogue, wonderful planes, and a host of some of the funniest people in movies in the cast."[43]

At 85 characters, Those Magnificent Men ... was the longest-titled film to be nominated for an Academy Award until the 2021 nominations of Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan.[44]

Box-office

At over two hours, Those Magnificent Men In their Flying Machines ... (most cinemas abbreviated the full title, and it was eventually re-released with the shorter title) was treated as a major production, one of three full-length 70 mm Todd-AO Fox releases in 1965 with an intermission and musical interlude part of the original screenings.[8] The film was initially an exclusive roadshow presentation where customers needed reserved seats purchased ahead of time. It was an immediate box-office success, out-grossing the similar car-race comedy The Great Race (1965). It stood up well against the slightly earlier It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963).[15]

According to Fox records, the film needed to earn $15,300,000 in worldwide rentals to break even and made $29,950,000.[45] In the United States, the film earned $14,000,000 in rentals,[46] becoming the fourth highest-grossing film of 1965. By September 1970, it had earned Fox an estimated profit of $10,683,000.[47]

Pseudo-sequel

The success of the film prompted Annakin to write (again with Jack Davies) and direct another race film, Monte Carlo or Bust! (1969), this time involving vintage cars, with the story set around the Monte Carlo Rally.[Note 2] Ron Goodwin composed the music for both films.

Awards

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Award | Best Writing, Story and Screenplay | Ken Annakin and Jack Davies | Nominated |

| British Academy of Film and Television Arts Awards | Best British Costume (Colour) | Osbert Lancaster and Dinah Greet | Won |

| British Academy of Film and Television Arts Awards | Best British Art Direction (Colour) | Thomas N. Morahan | Nominated |

| British Academy of Film and Television Arts Awards | Best British Cinematography (Colour) | Christopher Challis | Nominated |

| Golden Globes | Best Motion Picture – Musical/Comedy | Nominated | |

| Golden Globes | Best Motion Picture Actor – Musical/Comedy | Alberto Sordi | Nominated |

| Golden Globes | Most Promising Newcomer – Male | James Fox | Nominated |

References

Notes

- ^ Annakin was born in 1914, just as the era of aviation depicted in this film was ending, and although the film is a farce, the behaviour of the various aviators depicts the tensions between the European countries prior to the First World War. This sense of civility between European nationalities is remembered as the Entente cordiale.[8]

- ^ Monte Carlo or Bust was released in the US as Those Daring Young Men in their Jaunty Jalopies to capitalise on the popularity of the earlier film.[48]

Citations

- ^ "Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes (1965)". BFI. Retrieved 2022-07-27.

- ^ "Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes (1965)". BFI Film Forever. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Solomon (1989), p. 254.

- ^ "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Review: 'Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines'". Britmovie.co.uk. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Conversations with Ken Annakin". Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines DVD, 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Director's Voice-over Commentary". Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines DVD, 2004.

- ^ Kaufman, Richard. "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines: Ron Goodwin Lyrics". Lyricszoo. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Lysy, Craig (24 March 2011). "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines – Ron Goodwin". Movie Music UK. Retrieved 8 May 2013.[failed verification]

- ^ Lee (1974), p. 490.

- ^ a b c Carr, Jay. "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Novick (2002), p. 75.

- ^ McCann (2009), p. 190.

- ^ a b Munn (1983), p. 161.

- ^ Miles (1994), p. 124.

- ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedDVD 12 - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedDVD bonus2 - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedDVD2 - ^ "Cast: 'Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines or How I Flew From London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes'". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ "Flying at Brooklands". Flight. 1 (45): 705–706. 6 November 1909.

- ^ a b c d e "Behind the Scenes" featurette, Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines (DVD bonus), 20th Century Fox, 2004.

- ^ "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines (1965)". Kent Film Office. 10 October 1965. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Locations: Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines". IMDb. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ "RAF Henlow - The Film Set". Henlow Parish Council. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (27 July 2019). "Unsung Aussie Filmmakers: Don Sharp – A Top 25". Filmink.

- ^ Sharp, Don (2 November 1993). "Don Sharp Side 4" (Interview). Interviewed by Teddy Darvas and Alan Lawson. London: History Project. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Horatio Philipps and the Cambered Wing Design". The U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. 2003. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Wheeler (1965).

- ^ Wheeler (1965), pp.44-49.

- ^ Carlson (2012), p. 325.

- ^ Carlson (2012), p. 328.

- ^ Wheeler (1965), pp. 92-93

- ^ Wheeler (1965), p. 62

- ^ "Collection". Southward Car Museum. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ Wheeler (1965), pp. 27-35

- ^ Ellis (2005), p. 38.

- ^ Bowles, Robert (2006). "Avro Triplane". Airsceneuk.org.uk. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ Ellis (2005), p. 39.

- ^ Dowsett, Barry (2012). "James Henry 'Cole' Palen, (1925–1993)". Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (17 June 1965). "Movie Review: Those Magnificent Men In their Flying Machines (1965)". The New York Times.

- ^ "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines – Or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes (UK)". Variety. 1 January 1965. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines – Or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes: TV Guide Review". TV Guide.com. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ Haring, Bruce (27 March 2021). "'Borat Subsequent Moviefilm' Sets Guinness World Record For Oscar-Nominated Film With Longest Title". Deadline. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M (1988). The Fox that got away : the last days of the Zanuck dynasty at Twentieth Century-Fox. L. Stuart. p. 324.

- ^ Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century-Fox: A Corporate and Financial History Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 p 229

- ^ Silverman p 258

- ^ Hidick, E. W. (1969). Monte Carlo or Bust!. London: Sphere. ISBN 978-0-7221-4550-0.

Bibliography

- Annakin, Ken. So You Wanna Be a Director? Sheffield, UK: Tomahawk Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-9531926-5-6.

- Burke, John. Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes. New York: Pocket Cardinal, Pocket Books, 1965.

- Carlson, Mark. Flying on Film: A Century of Aviation in the Movies, 1912–2012. Duncan, Oklahoma: BearManor Media, 2012. ISBN 978-1-59393-219-0.

- Edgerton, David. "England and the Aeroplane: Militarism, Modernity and Machines". Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2013 ISBN 978-0141975160

- Ellis, Ken. "Evenin' All." Flypast No. 284, April 2005.

- Hallion, Richard P. Taking Flight: Inventing the Aerial Age from Antiquity through the First World War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-516035-5.

- Hardwick, Jack and Ed Schnepf. "A Viewer's Guide to Aviation Movies". The Making of the Great Aviation Films, General Aviation Series, Volume 2, 1989.

- Hodgens, R.M. "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines or How I Flew from London to Paris in Twenty-Five Hours and Eleven Minutes." Film Quarterly October 1965, Vol. 19, No. 1, p. 63.

- Lee, Walt. Reference Guide to Fantastic Films: Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror. Los Angeles, California: Chelsea-Lee Books, 1974. ISBN 0-913974-03-X.

- McCann, Graham. Bounder!: The Biography of Terry-Thomas. London: Arum Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1-84513-441-9.

- Miles, Sarah. Serves Me Right. London: Macmillan, 1994. ISBN 978-0-333-60141-9.

- Munn, Mike. Great Epic Films: The Stories Behind the Scenes. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1983. ISBN 0-85242-729-8.

- Novick, Jeremy. Benny Hill: King Lear. London, Carlton Books, 2002. ISBN 978-1-84222-214-0.

- Those Magnificent Men In their Flying Machines (1965) DVD (Including bonus features on the background of the film.) 20th Century Fox, 2004.

- Those Magnificent Men In their Flying Machines (1965) VHS Tape. 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, 1969.

- Searle, Ronald, Bill Richardson and Allen Andrews. Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines: Or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes. New York: Dennis Dobson/ W.W. Norton, 1965.

- Solomon, Aubrey. Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History (The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1.

- Temple, Julian C. Wings Over Woodley – The Story of Miles Aircraft and the Adwest Group. Bourne End, Bucks, UK: Aston Publications, 1987. ISBN 0-946627-12-6.

- Wheeler, Allen H. Building Aeroplanes for "Those Magnificent Men.". London: G.T. Foulis, 1965.

External links

- Pages with reference errors

- All articles with failed verification

- Articles with failed verification from August 2015

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with short description

- Template film date with 1 release date

- IMDb title ID not in Wikidata

- Rotten Tomatoes ID not in Wikidata

- 1960s adventure comedy films

- 1965 films

- 20th Century Fox films

- British adventure comedy films

- British aviation films

- Films about aviators

- Films about competitions

- Films directed by Ken Annakin

- Films scored by Ron Goodwin

- Films set in 1910

- Films set in England

- Films set in France

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- 1965 comedy films

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s British films

- British comedy films