Yellowbeard: Difference between revisions

m (1 revision imported) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|1983 film by Mel Damski}} | {{Short description|1983 film by Mel Damski}} | ||

{{Infobox film | {{Infobox film | ||

| name = Yellowbeard | | name = Yellowbeard | ||

| Line 146: | Line 143: | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

* {{IMDb title|id=0086618|title=Yellowbeard}} | * {{IMDb title|id=0086618|title=Yellowbeard}} | ||

* {{tcmdb title|21796|Yellowbeard}} | * {{tcmdb title|21796|Yellowbeard}} | ||

| Line 153: | Line 149: | ||

*{{AFI film|id=69902|title=Yellowbeard}} | *{{AFI film|id=69902|title=Yellowbeard}} | ||

{{Graham Chapman|state=collapsed}} | |||

{{Graham Chapman | |||

[[Category:1983 films]] | [[Category:1983 films]] | ||

Revision as of 14:03, 27 January 2023

| Yellowbeard | |

|---|---|

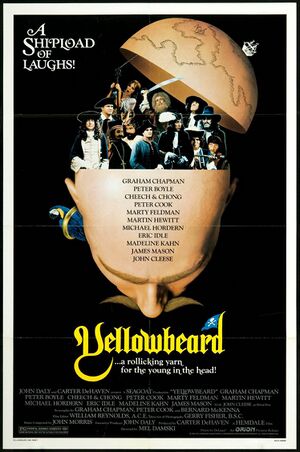

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mel Damski |

| Produced by | Carter De Haven |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Gerry Fisher |

| Edited by | William H. Reynolds |

| Music by | John Morris |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 96 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[2] |

| Box office | $4.3 million[3] |

Yellowbeard is a 1983 British comedy film directed by Mel Damski and written by Graham Chapman, Peter Cook, Bernard McKenna, and David Sherlock, with an ensemble cast featuring Chapman, Cook, Peter Boyle, Cheech & Chong, Martin Hewitt, Michael Hordern, Eric Idle, Madeline Kahn, James Mason, and John Cleese, and the final cinematic appearances of Marty Feldman, Spike Milligan, and Peter Bull.

Plot

In 1687, pirate Yellowbeard attacks the ship of inquisitor El Nebuloso and seizes a treasure hoard from the Spanish Main. Although his second-in-command Moon devised the attack plan, Yellowbeard treats him harshly and severs Moon's hand for touching the treasure. Yellowbeard continues piracy in the West Indies until he is betrayed by Moon and imprisoned in England for tax evasion.

Twenty years later, Yellowbeard is about to complete his prison sentence, having kept secret the location of his buried treasure from his torturers and from Moon's spy Gilbert. Commander Clement, a Royal Navy officer and head of Her Majesty's Secret Service,[a] provokes Yellowbeard by greatly extending his sentence. Yellowbeard escapes and visits his wife Betty's tavern to retrieve his treasure map. However, she destroyed the map after tattooing it onto the head of their son Dan, now twenty years old.

Clement and Gilbert each arrive and are eluded by Yellowbeard. Informant Blind Pew directs Clement to Yellowbeard's trail. Gilbert confronts Pew and exposes him as a government agent, turning the tavern patrons against him, but Pew is able to use his wit and prowess to defeat them.

Yellowbeard finds Dan who volunteers to help find the treasure. However, because Dan was raised as a gentleman by Lord Lambourne, Yellowbeard believes him unsuited to piracy and tries to take only Dan's head. Clement's men arrive, so Dan and Lambourne hide Yellowbeard with botanist Dr. Gilpin. They devise a plan to disguise Yellowbeard and travel to Jamaica as a botany expedition. Betty agrees to conceal their activities for a share, but her obvious lies raise Clement's suspicions. Meanwhile, Moon and Gilbert kill Pew.

Dan's group book passage in Portsmouth, pursued by Clement, Gilbert and Moon. Moon usurps leadership of a press gang and waylays Dan, Lambourne and Gilpin, impressing them into service on the Lady Edith under Captain Hughes. Following weeks of harsh "preemptive discipline" at sea, Dan confronts cruel Mr. Crisp and is knocked-out. Yellowbeard, who had secretly stowed away on the ship, overpowers Crisp to save the map and drops him into the sea. Moon informs Hughes that Dan is Yellowbeard's son, and Hughes arrests Dan, Lambourne and Gilpin for conspiracy to mutiny. Moon immediately engineers a mutiny and installs Dan as captain. That night, Yellowbeard alters the ship's course, leading Dan and Moon to suspect each other of the act.

Meanwhile, Clement questions Betty aboard his frigate while trying to intercept Yellowbeard. By happenstance, the Lady Edith's new course brings the ships together. To preserve the secrecy of his mission, Clement raises the French flag and is mystified when the Edith engages them despite being outgunned and outmanned. He feigns battle and withdraws.

The Lady Edith arrives at an island which matches the map. Yellowbeard covertly swims to shore while Dan and the others accompany foraging parties. However, El Nebuloso has a fortress on the island and Dan is captured. Lambourne and Gilpin find Yellowbeard and attack the fortress to rescue Dan. They meet no resistance, per Nebuloso's ruse to capture their leader and learn the treasure's location. However, his men are either killed by Yellowbeard or paralyzed by Gilpin's botanical extract. Nebuloso holds Dan hostage but Yellowbeard reveals himself and a terrified Nebuloso fatally falls into an acid pool.

Moon and his men arrive and a swordfight ensues. Yellowbeard withdraws to search for the treasure. Moon outfights Dan and backs him to the acid pool, but Nebuloso's daughter Triola, who had instantly fallen in love with Dan, knocks Moon into the acid. Meanwhile, Clement arrives on the island and Betty tries to guide his marines from her recollections of the map.

Dan finds Yellowbeard retracing his steps. Losing his place, Yellowbeard slices off Dan's hair to check the map and they soon unearth the treasure. Yellowbeard embraces Dan and inadvertently impales himself on Dan's dagger; approving of patricidal betrayal, Yellowbeard acknowledges Dan as his son before collapsing. Clement arrives and congratulates Dan for killing Yellowbeard while claiming the treasure for the queen. Triola immediately attaches herself to Clement.

Back at sea, Clement considers keeping the treasure and settling in the Americas. However, Dan, Yellowbeard, Lambourne, Gilpin and Betty seize the ship and hoist the Jolly Roger.

Cast

- Graham Chapman as Captain Yellowbeard

- Peter Boyle as Moon

- Cheech Marin as El Segundo

- Tommy Chong as El Nebuloso

- Peter Cook as Lord Lambourn

- Marty Feldman as Gilbert

- Martin Hewitt as Dan

- Michael Hordern as Dr. Gilpin

- Eric Idle as Commander Clement

- Madeline Kahn as Betty

- James Mason as Captain Hughes

- John Cleese as Harvey 'Blind' Pew

- Kenneth Mars as Mr. Crisp and Verdugo (dual role)

- Spike Milligan as Flunkie

- Stacey Nelkin as Triola

- Nigel Planer as Mansell

- Susannah York as Lady Churchill

- Beryl Reid as Lady Lambourn

- Ferdy Mayne as Mr. Beamish

- Peter Bull as Queen Anne

- Bernard Fox as Tarbuck

- Nigel Stock as Admiral

- Monte Landis as Prison Guard

- Greta Blackburn as Mr. Prostitute

- David Bowie as The Shark (uncredited)

Production

Development

Peter Cook remembered "It all started when Keith Moon, Sam Peckinpah, Graham Chapman and myself were dining at Trader Vic's. Keith suggested doing a movie about pirates and we were all discussing it and being enthusiastic, when I saw Sam, who was too tired to actually go to the lavatory, relieving himself in the artificial palm tree by the table. It was then that I thought the whole thing was rather unlikely to get off the ground."[5]

The original concept for the film was funded by Chapman's close friend Moon, who wanted to play the lead role, but was dropped early on because of his deteriorating health.[6]: 1

The film has a complicated development history, largely due to the amount of time taken to get funding. There are at least four versions of the script drafts. The one that is "truest to Chapman and McKenna's original version" is published in the book Yellowbeard: High Jinks on the High Seas.[6]: 37 Major difference between Chapman and McKenna's script, which was altered at Hollywood's request, is that the original has less emphasis on minor characters and more emphasis on the overall plot. Cook is credited as a writer because, in October 1980, Chapman asked Cook to help with one of the rewrites.[6]: 9

Casting

In casting, producer Carter De Haven wanted to choose actors that would broaden the film's appeal to American audiences.[2]

The actor set to play the romantic lead changed from Adam Ant to Sting to Martin Hewitt. Adam Ant was frustrated with production delays and quit. Sting wanted to play the role, but the producers thought the film was becoming too British. Hewitt is quoted as saying that "Sting should have had my part. For crying out loud, I would have hired Sting over me any day."[6]: 22

Haven told The New York Times, "I got the cast I wanted. All the actors are integral. They are not just playing cameo roles."[2]

David Bowie makes a cameo appearance as the Shark – a character named Henson who dons a rubber shark fin on his back. Bowie was on holiday in Mexico in late 1982 after completing his album Let's Dance when he met with Chapman and Idle on a beach, agreeing to make a cameo appearance. Bowie also appeared in the 50-minute behind-the-scenes feature titled Group Madness.[7]

Filming

Apart from a couple of weeks spent in England, the entire film including interiors was shot in Mexico.[2]

Chapman's friend Harry Nilsson created a preliminary soundtrack, including one song specifically for the film. This was not used because the producers felt he could not be relied on to finish it.[6]: 24–25

Three ships in the film were portrayed by Bounty II, built by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for the 1962 version of Mutiny on the Bounty. The pirate ship was named Edith, after Chapman's mother.

Marty Feldman died of a heart attack while filming in Mexico City in December 1982. His work on the film was nearly finished except for the scene of his character's death, filmed a few days later using a stunt double. Chapman said about Feldman's death: "I try to look at the positive side...I take pleasure knowing that Marty was back on form for his last role."[6]: 32

Chapman was not allowed to assist with the editing, and his comments on the first cut were ignored; these included shortening the credits, so that audience expectation was not too far raised, and making the jokes less obvious.[6]: 34

Reception

Critical response

The film received some praise, with the Los Angeles Times writing that there are "many moments of hilarity here",[8] but it was not a big box-office success, and received mostly negative reviews. Various reasons are suggested, such as the peculiar combination of British and American humour, and it being poorly timed given the movie climate, with other kinds of comedy being popular. DVD Verdict gives it 75 out of 100, but writes "It is, at times, hilarious, and contains all of the pieces of a great comedy. These pieces never come together to make a great film."[9] Roger Ebert gave the film one-and-a-half stars, and said "Yellowbeard is soon over and soon forgotten."[10] On Rotten Tomatoes the film has a 22% approval rating based on reviews from 9 critics.[11]

Actors' response

Cleese played a part out of loyalty to Chapman. He said he found the script to be one of the worst he had read, although it is unclear which version he was referring to. In an interview given in 2001, Cleese described Yellowbeard as "one of the six worst films made in the history of the world".[12]

Eric Idle mentioned Yellowbeard as one of the worst films he has ever made, but said he enjoyed making it. "Sometimes, the best times can be on the worst movies and vice versa, e.g. Yellowbeard, which I wouldn't have missed for the world."[13]

Group Madness documentary

During the production of Yellowbeard, Michael Mileham and Phil Schuman produced and directed a 45-minute behind-the-scenes documentary for Orion Pictures, entitled Group Madness: The Making of Yellowbeard. Mileham said he wanted to make the documentary because Yellowbeard had "more comics in it than any film since [1963's] It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World".[14] Mileham and his crew followed the Yellowbeard filmmakers and cast to locations in England and Mexico, documenting their off-screen antics and interviewing many cast members, including Chapman, Idle, Cleese, Feldman, Boyle, Cook and Kahn.[15]

Near the time of the 1983 release of Yellowbeard, Group Madness was syndicated to 75 television stations in the United States and broadcast only once on NBC on 11 June 1983, pre-empting Saturday Night Live.[14][16] In the mid-1990s, video copies of the documentary could be ordered from Mileham;[14] it was eventually released on DVD in 2007[17] and later streamed on Amazon.com.[18]

Notes

- ^ An anachronism, the Secret Service Bureau was not formed until 1909.[4]

References

- ^ "Yellowbeard (PG) (CUT)". British Board of Film Classification. 28 July 1983. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d Farber, Stephen (9 January 1983). "Ahoy! Just Over the Horizon, A Fleet of Pirate Movies". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Yellowbeard at Box Office Mojo

- ^ "1920: What's in a Name". SIS website. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ Cook, Peter (1984). "Speaking about 'Yellowbeard'". The Film Yearbook. p. 135.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chapman, Graham (2005). Yellowbeard: High jinks on the high seas. Carroll & Graf.

- ^ Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (revised and updated ed.). London: Titan Books. p. 670. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- ^ Parish, James Robert (1995). Pirates and Seafaring Swashbucklers on the Hollywood Screen: Plots, Critiques, Casts and Credits for 137 Theatrical and Made-for-television Releases. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-89950-935-8.

- ^ Judge Joel Pearce (23 June 2006). "DVD Verdict Review - Yellowbeard". DVD Verdict. Archived from the original on 2007-12-22. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (24 June 1983). "Yellowbeard (1983)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ^ "Yellowbeard". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ^ 2001 interview included as an extra on the DVD release of the John Cleese movie Clockwise.

- ^ "You Ask The Questions". The Independent. London. 6 October 1999. Archived from the original on 2013-03-15. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ a b c ten Cate, Hans (1995-12-21). "Pythonline's Daily Llama News: Michael Mileham's 'Group Madness' a Must-Have For Python Fans!". dailyllama.com. Pythonline's Daily Llama. Archived from the original on 2011-08-19. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

- ^ McCall, Douglas (12 November 2013). Monty Python: A Chronology, 1969-2012 (2nd ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-7864-7811-8.

- ^ "Group Madness:The Making of Yellowbeard". TV Guide. Radnor, Pennsylvania: Triangle Publications. 1983-06-11. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

- ^ The Weedmaster (2007-05-29). "On DVD For the First Time. Group Madness: The Making of Yellowbeard". cheechandchongfan.blogspot.com. Cheech and Chong Fans .com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-19. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

- ^ "Group Madness: The Making of Yellowbeard". Amazon.com. 2016. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

External links

- Articles with short description

- Template film date with 1 release date

- Pages using infobox film with unknown parameters

- IMDb title ID not in Wikidata

- 1983 films

- British adventure comedy films

- Films directed by Mel Damski

- Films scored by John Morris

- Films with screenplays by Graham Chapman

- 1980s adventure comedy films

- Pirate films

- Films set in the 18th century

- Orion Pictures films

- Cultural depictions of Anne, Queen of Great Britain

- Cultural depictions of Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough

- 1983 directorial debut films

- 1983 comedy films

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in Mexico City

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s British films