Joking Apart: Difference between revisions

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

===Structure=== | ===Structure=== | ||

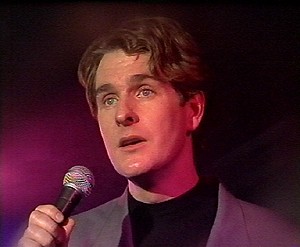

Many of the first six episodes of ''Joking Apart'' were constructed non-sequentially, with scenes from the beginning of the relationship juxtaposed with those from the end. Moffat describes this [[Nonlinearity|non-linear]] technique as a "romantic comedy, but a romantic comedy backwards because it ends with the couple unhappy".<ref name="fool"/> Moffat had experimented with non-linear narrative in ''Press Gang'', such as the episode "Monday-Tuesday".<ref>{{cite episode |title=Monday-Tuesday |series=Press Gang |credits=wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers |network=ITV |airdate=1989-04-03 |season=1 |number=11}}</ref> Various episodes of ''[[Coupling (UK TV series)|Coupling]]'' played with structure, such as the fourth series episode "9½ Minutes" which showed the same events from three perspectives.<ref>{{cite episode |title=9½ Minutes |series=Coupling |credits=wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Martin Dennis |network=BBC |airdate=2004-05-10 |season=4 |number=1}}</ref> | [[File:Joking Apart - Robert Bathurst.jpg|thumb|alt=A close-up shot of the character Mark holding a microphone|[[w:Robert Bathurst|Robert Bathurst]], as Mark, in a fantasy stand-up sequence. In the pilot, Bathurst was filmed against a completely black backdrop. According to Moffat, this looked "odd" for the viewer.<ref name="fool"/>]] | ||

Many of the first six episodes of ''Joking Apart'' were constructed non-sequentially, with scenes from the beginning of the relationship juxtaposed with those from the end. Moffat describes this [[w:Nonlinearity|non-linear]] technique as a "romantic comedy, but a romantic comedy backwards because it ends with the couple unhappy".<ref name="fool"/> Moffat had experimented with non-linear narrative in ''Press Gang'', such as the episode "Monday-Tuesday".<ref>{{cite episode |title=Monday-Tuesday |series=Press Gang |credits=wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers |network=ITV |airdate=1989-04-03 |season=1 |number=11}}</ref> Various episodes of ''[[w:Coupling (UK TV series)|Coupling]]'' played with structure, such as the fourth series episode "9½ Minutes" which showed the same events from three perspectives.<ref>{{cite episode |title=9½ Minutes |series=Coupling |credits=wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Martin Dennis |network=BBC |airdate=2004-05-10 |season=4 |number=1}}</ref> | |||

All of the episodes open with Bathurst portraying Mark Taylor, a sitcom writer, apparently performing [[stand-up comedy|stand-up]] in a small [[comedy club]]. These performances are fantasy sequences, playing out in the character's mind and portraying his internal creative processes as comedic monologues; these monologues mainly employ material from the character's failing marriage and are intended to show that "he thinks in [[Punch line|punchlines]], in comedy".<ref name="gritten">{{cite news |first=David |last=Gritten |title=Reviews |work=The Daily Telegraph|date=1993-01-08}}</ref> Episodes regularly cut back to these fantasy performances, which usually open with the signature line: "My wife left me ...". Moffat felt that audiences needed to know from the start that the relationship would not survive.<ref name="fool"/> However, it was unclear to some viewers that the fantasy sequences were set in the writer's mind; many journalists reported that the character Mark was a stand-up comic,<ref name="Keal"/> not a sitcom writer. | All of the episodes open with Bathurst portraying Mark Taylor, a sitcom writer, apparently performing [[w:stand-up comedy|stand-up]] in a small [[w:comedy club|comedy club]]. These performances are fantasy sequences, playing out in the character's mind and portraying his internal creative processes as comedic monologues; these monologues mainly employ material from the character's failing marriage and are intended to show that "he thinks in [[w:Punch line|punchlines]], in comedy".<ref name="gritten">{{cite news |first=David |last=Gritten |title=Reviews |work=The Daily Telegraph|date=1993-01-08}}</ref> Episodes regularly cut back to these fantasy performances, which usually open with the signature line: "My wife left me ...". Moffat felt that audiences needed to know from the start that the relationship would not survive.<ref name="fool"/> However, it was unclear to some viewers that the fantasy sequences were set in the writer's mind; many journalists reported that the character Mark was a stand-up comic,<ref name="Keal"/> not a sitcom writer. | ||

In the fantasy sequences for the pilot, Bathurst was filmed against a completely black backdrop, which Moffat describes as "hell to look at".<ref name="fool"/> For the series, the sequences were filmed in a real club. Moffat describes this as the "wrong direction" as it became unclear that the fantasy sequences were "not real".<ref name="fool"/> Moffat observes that, like ''[[Seinfeld]]'', an American sitcom that used a similar device, ''Joking Apart'' used less of the stand-up as the series progressed. In retrospect, Moffat regrets including the stand-up sequences.<ref name="fool"/> Bathurst, however, has considered refilming them as a [[video diary]]. Now with older features, he can portray a Mark Taylor reflecting on his earlier life.<ref name="conbath2">{{cite web |title=In Conversation: Robert Bathurst, Part 2 |work=Joking Apart.co.uk |url=http://www.jokingapart.co.uk/in_conversation/robert_bathurst_p2.htm |access-date=2007-03-03}}</ref> Both are very critical of the sequences in the DVD audio commentaries. The sequences have also drawn the sharpest criticisms from reviewers.<ref name="sci-fi1"/> The second series followed a more linear structure, although it retained the stand-up sequences.<ref name="s2comm">''Joking Apart'' Series 2, DVD audio commentary</ref> | In the fantasy sequences for the pilot, Bathurst was filmed against a completely black backdrop, which Moffat describes as "hell to look at".<ref name="fool"/> For the series, the sequences were filmed in a real club. Moffat describes this as the "wrong direction" as it became unclear that the fantasy sequences were "not real".<ref name="fool"/> Moffat observes that, like ''[[w:Seinfeld|Seinfeld]]'', an American sitcom that used a similar device, ''Joking Apart'' used less of the stand-up as the series progressed. In retrospect, Moffat regrets including the stand-up sequences.<ref name="fool"/> Bathurst, however, has considered refilming them as a [[w:video diary|video diary]]. Now with older features, he can portray a Mark Taylor reflecting on his earlier life.<ref name="conbath2">{{cite web |title=In Conversation: Robert Bathurst, Part 2 |work=Joking Apart.co.uk |url=http://www.jokingapart.co.uk/in_conversation/robert_bathurst_p2.htm |access-date=2007-03-03}}</ref> Both are very critical of the sequences in the DVD audio commentaries. The sequences have also drawn the sharpest criticisms from reviewers.<ref name="sci-fi1"/> The second series followed a more linear structure, although it retained the stand-up sequences.<ref name="s2comm">''Joking Apart'' Series 2, DVD audio commentary</ref> | ||

===Music and titles=== | ===Music and titles=== | ||

Revision as of 09:58, 29 December 2022

| Joking Apart | |

|---|---|

The opening title is superimposed over a stack of legal documents. | |

| Created by | Steven Moffat |

| Directed by | Bob Spiers |

| Starring | Robert Bathurst Fiona Gillies Tracie Bennett Paul Raffield Paul Mark Elliott |

| Theme music composer | Chris Rea |

| Opening theme | "Fool (If You Think It's Over)" (also end theme) |

| Composers | Kenny Craddock, Colin Gibson |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Original language | English |

| No. of series | 2 |

| No. of episodes | 12 (+ pilot) (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Producer | Andre Ptaszynski |

| Running time | 30 minutes |

| Original release | |

| Network | BBC2 |

| Release | 7 January 1993 – 7 February 1995 |

| Related | |

| Coupling | |

Joking Apart is a BBC television sitcom written by Steven Moffat about the rise and fall of a relationship. It juxtaposes a couple, Mark (Robert Bathurst) and Becky (Fiona Gillies), who fall in love and marry, before getting separated and finally divorced. The twelve episodes, broadcast between 1993 and 1995, were directed by Bob Spiers and produced by Andre Ptaszynski for independent production company Pola Jones.

The show is semi-autobiographical; it was inspired by the then-recent separation of Moffat and his first wife.[1][2] Some of the episodes in the first series followed a non-linear parallel structure, contrasting the rise of the relationship with the fall. Other episodes were ensemble farces, predominantly including the couple's friends Robert (Paul Raffield) and Tracy (Tracie Bennett). Paul Mark Elliott also appeared as Trevor, Becky's lover.

Scheduling problems meant that the show attracted low viewing figures. However, it scored highly on the Appreciation Index and accrued a loyal fanbase. One fan acquired the home video rights from the BBC and released both series on his own DVD label.[3]

Production

Inception

By 1990, Moffat had written two series of Press Gang, but the programme's high cost along with organisational changes at Central cast its future in doubt.[4] As Moffat wondered what to do next and worried about his future employment, Bob Spiers, Press Gang's primary director, suggested that he meet with producer Andre Ptaszynski to discuss writing a sitcom.[2] Moffat's father had been a headteacher and Moffat himself had taught English before writing Press Gang, so his initial proposal was a programme similar to what would become Chalk, a series that eventually aired in 1997.[5]

As he was separating from his wife, Moffat was going through a difficult period and aspects of it coloured his creative output.[4] He introduced a proxy of his wife's new partner into the Press Gang episode "The Big Finish?", the character Brian Magboy (Simon Schatzberger). Moffat scripted unfortunate situations for the Magboy character, such as having a typewriter drop on his foot. Moffat says that the character's name was inspired by his wife's: "Magboy: Maggie's boy".[4]

During the pitch meeting at the Groucho Club, Ptaszynski realised that Moffat was talking passionately about his impending divorce and suggested that he write about that instead of his initial proposal, a school sitcom.[5] Taking Ptaszynski's advice, Moffat's new idea was about "a sitcom writer whose wife leaves him".[6] Speaking about the autobiographical elements of the show, the writer jokes that he has to remember that his wife didn't leave him for an estate agent; his wife was an estate agent.[7] In 2003, Moffat told The New York Times that his "ex-wife wasn't terribly pleased about her failed marriage being presented as a sitcom on BBC2 on Monday nights".[8] In an interview with Richard Herring, Moffat says that "the sit-com actually lasted slightly longer than my marriage".[9] Conversely, his later sitcom Coupling was based on his relationship with his second wife, TV producer Sue Vertue.[10] Moffat reused the surname 'Taylor', which is Mark's surname in Joking Apart, for Jack Davenport's character Steve in Coupling.

Recording

The pilot, directed by John Kilby, was filmed at Pebble Mill in Birmingham on 9–10 August 1990.[11] It is practically identical to the first episode of the series proper;[12] some scenes are even reused, notably the scene with Mark and Becky meeting when he accidentally turns up at a funeral. The reused footage gave rise to the first episode's shared director credit between Spiers and Kilby.[13] The stand-up sequences were shot against a black background. Although this made it clearer that they were not "real", Moffat thought that it looked odd.[6] The pilot was transmitted on BBC2 as part of its Comic Asides series of pilot shows on 12 July 1991.[11]

Moffat had written all six episodes of the first series before recording commenced. With series two, he had written only the first four episodes by the time recording had commenced,[14] only delivering the final episode by the first day of rehearsals.[7]

All of the location shots were filmed at the beginning of the production block.[15] Recording for the first series of six episodes began on location in the first half of April 1992[11] and were mainly filmed in Chelsea within a short distance from the director's home.[16] The stand-up sequences were filmed in the Café Des Artistes on London's Fulham Road, now known as the Valmont Club,[11] and were shot for the benefit of the studio audience, with the intention of reshooting them later for the broadcast version. Robert Bathurst has complained that, in order to save £5,000, this promised reshoot never materialised.[6] The close ups of Bathurst were filmed in the studio for the second series, with stock footage of the club's audience reused.[11]

After the exterior shots had been filmed, the episodes were recorded at BBC Television Centre in April and May 1992 for the first series, and 12 November until 18 December 1993 for the second.[11] Studio recording sessions were normally completed quickly; Gillies recalls "an hour and a half, tops".[15] To a large extent, the editing occurred live during the studio recording with only tightening later. At the end of the recording on Sunday evenings Spiers would review the show before retiring to the bar, with the bulk of the work complete. Moffat contrasts this with the editing of modern sitcoms, which, he says, are edited more like film.[15]

Structure

Many of the first six episodes of Joking Apart were constructed non-sequentially, with scenes from the beginning of the relationship juxtaposed with those from the end. Moffat describes this non-linear technique as a "romantic comedy, but a romantic comedy backwards because it ends with the couple unhappy".[6] Moffat had experimented with non-linear narrative in Press Gang, such as the episode "Monday-Tuesday".[17] Various episodes of Coupling played with structure, such as the fourth series episode "9½ Minutes" which showed the same events from three perspectives.[18]

All of the episodes open with Bathurst portraying Mark Taylor, a sitcom writer, apparently performing stand-up in a small comedy club. These performances are fantasy sequences, playing out in the character's mind and portraying his internal creative processes as comedic monologues; these monologues mainly employ material from the character's failing marriage and are intended to show that "he thinks in punchlines, in comedy".[19] Episodes regularly cut back to these fantasy performances, which usually open with the signature line: "My wife left me ...". Moffat felt that audiences needed to know from the start that the relationship would not survive.[6] However, it was unclear to some viewers that the fantasy sequences were set in the writer's mind; many journalists reported that the character Mark was a stand-up comic,[20] not a sitcom writer.

In the fantasy sequences for the pilot, Bathurst was filmed against a completely black backdrop, which Moffat describes as "hell to look at".[6] For the series, the sequences were filmed in a real club. Moffat describes this as the "wrong direction" as it became unclear that the fantasy sequences were "not real".[6] Moffat observes that, like Seinfeld, an American sitcom that used a similar device, Joking Apart used less of the stand-up as the series progressed. In retrospect, Moffat regrets including the stand-up sequences.[6] Bathurst, however, has considered refilming them as a video diary. Now with older features, he can portray a Mark Taylor reflecting on his earlier life.[21] Both are very critical of the sequences in the DVD audio commentaries. The sequences have also drawn the sharpest criticisms from reviewers.[22] The second series followed a more linear structure, although it retained the stand-up sequences.[23]

Music and titles

"Fool (If You Think It's Over)", written by Chris Rea, was used for both the opening and closing credit sequences. The original Rea version was used for the pilot's closing credits, but for the series it was performed by Kenny Craddock, who arranged the incidental music with Colin Gibson.[24] Beginning with a saxophone, only the chorus of the theme song accompanied the opening titles. These ran over legal imagery and a sequence of images of famous separated couples, including Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe; Winnie and Nelson Mandela; Princess Anne and Mark Phillips, and culminating in Mark and Becky. The closing credits featured a verse and chorus. The first part of the closing credits was usually over a still of the final frame, and faded to black with the line "All dressed in black."[25]

Characters

Mark Taylor (Robert Bathurst) is a television sitcom writer. Other than episode one, where he is shown working on a script and references to a show of his that had aired during a dinner with Robert and Tracy the night before, his work is hardly mentioned. Mark is quick-witted, and the stand-up sequences indicate that he thinks in one-liners.[6] However, this proves to be the downfall of his marriage with Becky, who says that she didn't sign on to become his "lawfully wedded straight man". In one episode, Mark jokes about worrying if his virginity will heal back; Becky articulates her frustration by responding "What page is that on?" Identifying his insecurities, she points out that the "thing about someone who uses humour as a weapon, is not the sense of humour, but the fact that they need a weapon".[26] In interviews, Bathurst has compared Steven Moffat to his character: Mark is "a man whose wife leaves him because he talks in one-liners. And Steven Moffat's wife had just left him, because he talks in one-liners."[20]

Robert Bathurst, a former Footlights president, was cast as Mark Taylor. He was performing on a live topical programme on BSB called Up Yer News. A fellow performer on that show also auditioned for the part at what is now the Soho Theatre, then the old Soho Synagogue in Dean Street, and claimed that he would break Bathurst's legs if the latter got the job. In a 2005 interview, Bathurst recalls that the threat seemed not to be entirely jocular.[6] Bathurst speaks very highly of Joking Apart, identifying it as a "career highlight" and the most enjoyable job he has ever done.[27][28] Retrospectively, he wishes that he had "roughened up" Mark, as he was "too designery".[29]

Becky Johnson/Taylor (Fiona Gillies) meets Mark at a funeral and they eventually marry. Although irritated at being his comic foil, she is capable of her own quick-witted put-downs. In episode 3, for example, she wins an impromptu one-liner contest over Mark, whose put-downs fall flat.[30] Becky is shown as an independent woman, meeting Mark on her terms.[31] The first series revolves around her leaving Mark for estate agent Trevor, whom she subsequently cheats on in series two. This was Fiona Gillies' first major television role, having appeared in "The Hound of the Baskervilles", a 1988 episode of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, and the mini-series Mother Love. She was aware that some of her dialogue was based on what had been said to Moffat during his own separation.[6]

Robert and Tracy Glazebrook (Paul Raffield and Tracie Bennett) are their "increasingly bizarre and totally dim friends".[32] They are initially Becky's friends, but soon befriend Mark, comforting him on the night Becky leaves him.[33] Tracy, as Tracie Bennett identifies, is a stereotypical Tracy—normally a dysphemism for an intellectually inadequate, usually blonde, female. However, "she's not a bimbo: she's quite clever in her own logic".[6] Bennett jokes that she was quite offended that such a character was named Tracy.[15] Tracy's catchphrase of "you're a silly" was originally Moffat's typographical error, which Bennett faithfully reproduced in her performance. They decided that the amended version worked well for the character.[15]

They are both naive about sex and technology. Tracy, for example, attempts to telephone Robert to inform him that he's lost his mobile phone,[34] and believes that she is a lesbian when she discovers her husband in women's clothing.[35] They have a baby, who is seen or referred to occasionally. This reflects, as the writer observes, Moffat's inexperience of looking after children at the time.[36][37]

Trevor (Paul Mark Elliott) is Becky's lover. His job as an estate agent regularly provokes derision from Mark. (Moffat's ex-wife was an estate agent.)[5] He is himself cheated on in the second series, as Becky dates her solicitor Michael (Tony Gardner). Trevor's debut appearance is in the third episode where he and Becky go to Robert and Tracy's house for dinner, but he generally features less regularly than the main ensemble.

Episodes

| Series | Episodes | Originally aired | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First aired | Last aired | |||

| Pilot | 12 July 1991 | |||

| 1 | 6 | 7 January 1993 | 11 February 1993 | |

| 2 | 6 | 3 January 1995 | 7 February 1995 | |

Series one

The first episode showed the couple meeting at a funeral, marrying, and going through the honeymoon phase. The last section of the episode features a confrontation between Becky and Mark, in which the former admits that she is an adulteress before realising that all of her friends were hiding around her living room in preparation for a surprise party for her.[26] The story continues directly into episode two, when Robert and Tracy return to the flat to check on Mark after his wife's departure. The three recall the circumstances in which they had first met. After their first date, the couple go back to Becky's flat. While she is in the bathroom, he strips down to his boxer shorts and handcuffs himself to the bedpost. Unable to free himself, Robert and Tracy walk in on him.[33] Moffat used a similar scenario for the Coupling episode "The Freckle, the Key, and the Couple who Weren't"[38] and reveals in its audio commentary that it is based on a situation with one of his ex-girlfriends.[39]

In the third episode, Mark arrives at Robert and Tracy's house on the wrong night for a dinner party. The couple are entertaining that night, but are instead expecting Becky and her new boyfriend Trevor. Hopeful of a reconciliation, Mark assumes that his friends are trying to smooth things over between them. They spend the evening trying to keep Mark and Trevor apart, each not knowing that the other is also there.[30] Episode five makes extensive use of what Moffat labels "techno-farce", which uses technology, predominantly telephones, to facilitate the farcical situations.[15] Moffat considers this episode the best of the show.[15] Discussing the series as a whole, he feels that the story ends after this episode.[7] It begins when Mark attempts to return Robert's "portable telephone" and ends with Robert threatening to shoot Mark after the latter has slept with Tracy. The series ends with Becky and Trevor, and Robert and Tracy reconciling their relationships and Mark being left alone.[40]

Series two

The format was changed for this series, with the dual timelines and much of the flashbacks dropped for a more linear narrative.[41] Moffat felt that the relationship had already been sufficiently established in the first series so there was little point returning to the start.[42] Set two months after the end of series one, Mark meets Becky in a newsagent, where he is purchasing pornographic magazines. He discovers the location of Becky and Trevor's house and breaks in using Tracy's keys. However, he is forced to hide under the bed when Becky and Trevor return home. Listening to them having sex, he becomes optimistic when he thinks that Becky begins to shout his name ("M..."). The name turns out to be Michael (Tony Gardner), Becky's solicitor with whom she is now cheating on Trevor.[43]

Robert and Tracy are given more stories than in the first series.[41] Their main story arc begins in the third episode when Robert is caught by all of the main characters and his parents in a maid's outfit being spanked by a prostitute.[31] The couple temporarily separate while Robert experiments with cross-dressing, but they are reunited by the end of the series.

The fourth episode features a scene where Mark jams his dressing gown in the door and is forced to hide naked in his new neighbour's flat. This sequence was Moffat's revenge for Bathurst's late arrival at the series one press launch at the Café Royal in Regent Street, London. Moffat threatened that if they ever did a second series he would write a whole episode in which Bathurst was naked.[20][44] After being mistaken for a flasher,[45] Mark is punched by his neighbour's brother. When he awakens he is confronted by a man (Kerry Shale) in a red polo neck jumper who claims to be "his very best friend".[35] In the fifth episode it transpires that the man, who identifies himself as Dick, is the personification of Mark's penis.[46]

The final episode begins after Becky and Michael had slept together while house sitting for Tracy and Robert, and Michael hides in the bathroom when the latter couple return. Tracy phones a morning television phone-in show (hosted by Michael Thomas and Helen Atkinson-Wood, with appearances by Rachael Fielding and Jonathan Barlow), and when she realises that the show's divorce expert is hiding in her bathroom she takes on his role (with a heavy Northern accent, actually a slightly exaggerated version of Bennett's own voice) to give herself advice on the other line.[47] Bennett says this was the hardest thing she has had to do in her career.[48]

Scheduling

After the pilot was transmitted on 12 July 1991, the BBC were interested in a series. However, Moffat had signed on to write the third and fourth series of Press Gang as one twelve-episode block so it was not until 1992 that they produced the series.[42] After being postponed from the autumn schedules, the first series was transmitted on Thursday evenings on BBC2 from 7 January until 11 February 1993.

The second series was filmed in late 1993. However, the controller of BBC2, Michael Jackson, had little faith in the project at the time, which, according to the writer, he now admits was wrong.[42] Jackson felt that it was too mainstream for BBC2 and not mainstream enough for BBC1.[42] The second series was scheduled to air from 11 June 1994, but was delayed many times.[11] Bathurst articulates the group's frustration at the delay:

Every so often, I’d get a call from the producer saying, it’s going out at this time. The publicity people would be alerted, then we’d get a call saying no, it’s not, it’s been put back. That happened six times, I think, altogether – seven reschedules in a year or so ... It was extraordinary and inexplicable, and just one of these things that happen. I mean, a lot of shows are left on people’s desks and they hardly get seen, and Joking Apart was certainly one of those. Meanwhile, they were making about four series of The Brittas Empire, and you thought, "Bloody Hell! Come on, surely….?" To my mind, our show was a very superior product, and it upset me that other shows, which I, personally, felt were broader and less interesting, were getting precedence.[21]

The first series was repeated in preparation for the six episodes of the second series, which began transmission on Tuesday evenings from 3 January until 7 February 1995. The second series was only transmitted once even though the BBC had paid to show it twice.[42] Moffat feels that the delay damaged the series because such bad scheduling hinders returning audiences and that the two-year gap meant that it seemed as if Mark "had been banging on about this sodding divorce for an awfully long time!"[42]

After winning the Montreux award it seemed inevitable that the show would get a third series. At a Christmas party, a BBC executive expressed a wish for the ratings of a third series "to go like Everest", indicating a steep slope with his hands. Bathurst replied, "But, Everest goes down the other side ..."[49] The show was not recommissioned. Moffat says that he had no idea for a third series anyway, as it would have been difficult to contrive how a group of people who did not particularly like each other would get together so regularly.[16]

Reception

The scheduling problems meant that the show did not get the momentum to achieve high viewing figures.[3] Moffat jokes that "the eight people who saw it were very happy indeed".[50] However, as Bathurst observes, "there's an underground of people who like it".[28] The show rated highly on the Appreciation Index, meaning that viewers thought very highly of the programme.[3] Bathurst says that drunks on the London Underground tell him in detail the plot of their favourite episode. The cast claim that the programme has a timeless, universal appeal as there are no time-specific references apart from the typewriter and the size of the mobile telephones.[6] Gillies says that her accountant watches it to cheer himself up, while Bathurst recalls that a friend cheered so loudly when Mark pushes avocado into Trevor's face in the third episode[30] that he woke his son.[6]

Critical reception was generally positive. In his overview of Moffat's celebrated Press Gang, Paul Cornell said that the writer "continues to impress" with Joking Apart.[51] The Daily Express said that it was "flavoured with a delicious bitterness about the perfidy of women and the conscious-less nature of the male orgasm, it was plotted with the intricacy of a French farce".[52] Another reviewer for the Express commented that "it's quite funny and an acute analysis" of the modern divorce, and that the first episode was "distinctly promising".[53] Similarly DVD Review comments that "Moffat's distillation of his marriage melting down is as precise a piece of comic writing as you're likely to find."[54]

Not all reviews were completely positive. Criticising Bathurst for being too handsome to convey the frustrations of a writer, The Daily Telegraph said that the show had "its problems but possesses a dark, mordant wit".[19] William Gallagher comments that "Press Gang was pretty flawless, but Joking Apart would veer from brilliance to schoolboy humour from week to week."[55]

While the transmission of series two was being delayed by BBC 2 controller Michael Jackson, the show won the Bronze Rose of Montreux[2] and was entered for the Emmys.[3] The show was remade in Portugal but used a linear structure rather than the flashbacks.[14] Moffat reflects that although the remake is "not as dark or ground-breaking" as the original, it is "probably more fun" because it ends happily.[9]

Home media

Both series have been released on DVD. A fan of the show, Craig Robins, bought the rights from 2Entertain, BBC Worldwide's DVD publishing company, and released it on his own independent label, Replay DVD.[2] Robins put up £30,000 of his own money to buy the rights and produced the series one disc.[56] As a professional videotape editor, Robins was able to restore the video, and author the disc himself, using a piece of freeware to transcribe the dialogue for the subtitles.[2]

The first series was released on DVD on 29 May 2006.[57] It contains audio commentaries on four of the episodes from Moffat, Bathurst, Gillies and Bennett. It also contains a featurette, "Fool If You Think It's Over", with retrospective interviews. The second series was released on 17 March 2008 as a two-disc set. It contains audio commentaries on all episodes: five featuring a mix of Moffat, Bathurst, Gillies, Bennett, Raffield and Ptaszynski, with episode two featuring Spiers, and production manager Stacey Adair that concentrates on the behind-the-scenes production.[45] The pilot from Comic Asides is also included on Disc 2, along with a complete set of Series Two scripts in Portable Document Format (PDF) and a PDF article entitled "Joking Apart in the Studio". The release includes a companion booklet.[45]

Replay DVD was commended in reviews for the quality of the disc.[22] DVD Times reports that "Joking Apart looks much sharper than the average television show on DVD. The colours are also much richer and have obviously been fixed throughout to present a more uniform image while the picture is bright and clear."[58] The featurette on the series 1 set is labelled "a great little feature", with Moffat particularly praised for his contribution. DVD Times identifies "a real sense of friendship and of a real liking for this show" within the commentaries,[58] highlighting that Moffat "sounds really happy ... for Joking Apart to have finally gotten some recognition".[45]

See also

- On The Up, another sitcom about the failure of a marriage

References

- ^ Sternbergh, Adam (7 September 2003). "Selling Your Sex Life (page 2)". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Kibble-White, Graham (May 2006). "Fool If You Think It's Over". Off the Telly. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d Jarvis, Shane (8 May 2006). "Farce that rose from the grave". The Telegraph. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Moffat, Steven; Sawalha, Julia, "The Big Finish?" Press Gang: Series 2 DVD audio commentary

- ^ a b c Ptaszynski, Andre; Moffat, Steven, Joking Apart, Series 2, Episode 1 DVD audio commentary

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Fool if You Think It's Over, featurette, Joking Apart, Series 1 DVD, Dir. Craig Robins

- ^ a b c Moffat, Steven, Joking Apart, Series 2, Episode 6 DVD audio commentary

- ^ Sternbergh, Adam (7 September 2003). "Selling Your Sex Life (page 3)". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ^ a b Herring, Richard (1997). "Interview With Steven Moffat". The Guardian Guide. Archived from the original (Reproduced on Richard Herring's website) on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ "Coupling". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gallagher, William. "Joking Apart", Inlay booklet, Series 2 DVD, ReplayDVD.

- ^ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/Suggestions' not found.

- ^ "Comparing the Pilot and Episode One". jokingapart.co.uk. Retrieved 13 February 2007.

- ^ a b Moffat, Steven, Joking Apart, Series 1, Episode 4 DVD audio commentary

- ^ a b c d e f g Moffat, Steven, Joking Apart Series 1, Episode 5, DVD audio commentary

- ^ a b "In Conversation: Steven Moffat, Part 4". jokingapart.co.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ^ wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (3 April 1989). "Monday-Tuesday". Press Gang. Season 1. Episode 11. ITV.

- ^ wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Martin Dennis (10 May 2004). "9½ Minutes". Coupling. Season 4. Episode 1. BBC.

- ^ a b Gritten, David (8 January 1993). "Reviews". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ a b c Keal, Graham (30 January 2005). "New role suits Cold Feet star". The Sunday Sun. Archived from the original on 4 July 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- ^ a b "In Conversation: Robert Bathurst, Part 2". Joking Apart.co.uk. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- ^ a b Packer, Charles. "Joking Apart: The Complete First Series". Sci-fi Online. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- ^ Joking Apart Series 2, DVD audio commentary

- ^ "The Composers: Kenny Craddock". jokingapart.co.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- ^ Eleven of the episodes follow this, whereas Series 1 Episode 3 is moving video.

- ^ a b wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (7 January 1993). "Series 1, Episode 1". Joking Apart. Season 1. Episode 1. BBC 2.

- ^ "Ticketmaster Interviews: Robert Bathurst". Ticketmaster. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ a b Wylie, Ian (4 February 2005). "Robert's fatherly fear". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ^ Rai, Bindu (4 October 2008). "Bathurst toons in to finance". Emirates Business 24/7. Archived from the original on 8 October 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^ a b c wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (21 January 1993). "Series 1, Episode 3". Joking Apart. Season 1. Episode 3. BBC 2.

- ^ a b wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (17 January 1995). "Series 2, Episode 3". Joking Apart. Season 2. Episode 3. BBC 2.

- ^ Evans, Jeff (1995). The Guinness Television Encyclopedia. Guinness. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-85112-744-6.

- ^ a b wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (14 January 1993). "Series 1, Episode 2". Joking Apart. Season 1. Episode 2. BBC 2.

- ^ wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (5 February 1993). "Series 1, Episode 5". Joking Apart. Season 1. Episode 5. BBC 2.

- ^ a b wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (24 January 1995). "Series 2, Episode 4". Joking Apart. Season 2. Episode 4. BBC 2.

- ^ Moffat, Steven, Joking Apart Series 1 Episode 3, DVD audio commentary

- ^ Moffat, Steven, Joking Apart Series 2, Episode 3 DVD audio commentary

- ^ wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Martin Dennis (21 October 2002). "The Freckle, the Key, and the Couple who Weren't". Coupling. Season 3. Episode 5. BBC Two.

- ^ Moffat, Steven; Davenport, Jack, "The Freckle, the Key, and the Couple who Weren't" Coupling Series 3, DVD audio commentary.

- ^ wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (11 February 1993). "Series 1, Episode 6". Joking Apart. Season 1. Episode 6. BBC 2.

- ^ a b Packer, Charles. "Joking Apart: The Complete Second Series". Sci-fi Online. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f "In Conversation: Steven Moffat, Part 3". jokingapart.co.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ^ wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (3 January 1995). "Series 2, Episode 1". Joking Apart. Season 2. Episode 1. BBC 2.

- ^ Moffat, Steven; Bathurst, Robert, Joking Apart, Series 2 Episode 4, DVD audio commentary

- ^ a b c d McCusker, Eamonn (13 March 2008). "Joking Apart: Complete Series 2". DVD Times. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (31 January 1995). "Series 2, Episode 5". Joking Apart. Season 2. Episode 5. BBC 2.

- ^ wr. Steven Moffat, dir. Bob Spiers (7 February 1995). "Series 2, Episode 5". Joking Apart. Season 2. Episode 6. BBC 2.

- ^ Tracie Bennett, Joking Apart, Series 2, Episode 6 DVD audio commentary.

- ^ Ellard, Andrew (25 June 2001). "Mr Flibble Talks To Robert Bathurst: Talented Todhunter". Red Dwarf.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ Coupling: Behind the Scenes, featurette (2002, prod./dir. Sarah Barnett & Christine Wilson) Coupling Season 1 DVD (Region 1), BBC Video, ISBN 0-7907-7339-2

- ^ Paul Cornell (1993) "Press Gang" In: Cornell, Paul.; Day, Martin; Topping, Keith (1993). The Guinness Book of Classic British TV. Guinness. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-85112-543-5.

- ^ Forwood, Margaret (13 February 1993). "unknown title". Daily Express.

- ^ Paton, Maureen (8 January 1993). "unknown title". Daily Express.

- ^ Glasby, Matt (April 2008). "Joking Apart". DVD Review.

- ^ Gallagher, William (30 August 2001). "The week's TV: Seen it all before?". BBC News. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ Steven Moffat (3 July 2006). Front Row (Interview). Interviewed by Mark Lawson. London: BBC Radio 4.

{{cite interview}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Replay DVD". Replay DVD. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ a b McCusker, Eamonn (13 March 2008). "Joking Apart: Complete Series 1". DVD Times. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

External links

- Joking Apart Unofficial Site, with episode guides and extended interviews with Moffat and Bathurst

- Joking Apart at British Comedy Guide

- Joking Apart at IMDb

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 errors: missing title

- Articles with short description

- Use dmy dates from December 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Pages using infobox television with unknown parameters

- IMDb title ID not in Wikidata

- 1990s British sitcoms

- 1993 British television series debuts

- 1995 British television series endings

- BBC television sitcoms

- British stand-up comedy television series

- English-language television shows

- Works about divorce